Image Credit: salon.com

Today is National Eros Day. If all goes as planned couples everywhere will exchange love tokens, consume chocolate, and passionately express their love for one another. Even if we poke fun at them, these are some of the conventions of Valentine's Day just like grilling and fireworks are conventional for the Fourth of July. But Valentine's Day is a peculiar holiday because many of its conventions--and certainly its iconography--are literary (instead of religious, nationalistic, or folkloric). To my knowledge it's the only widely celebrated holiday that, simply by virtue of its subject matter, has its own well-established poetic tradition and form: the tradition of courtly love poetry and the form of the sonnet. I ask the reader to accept this slightly shaky premise as I make the claim, just for fun, that Valentine's Day makes us all into poets.

I didn't say good poets. The Valentine's Day-inspired "poems" I will discuss here are hardly traditional, and perhaps not very clever. But poets have always insisted that their declarations of love are bungled and artless. Renaissance sonneteer Sir Philip Sidney says that idolizing one's love in verse is for fools "who fare like him that both / Lookes to the skies, and in a ditch doth fall." Yet, like Sidney's devoted Astrophil, fools cannot ignore Love's call to "bend hitherward your wit" (Astrophil and Stella 19). On Valentine's Day especially that call is deafening.

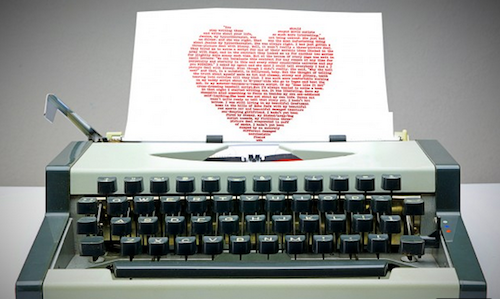

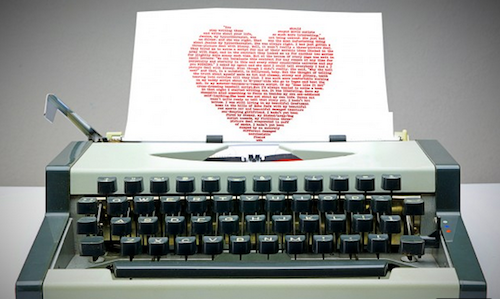

The illustration (above) to writer David Henry Sterry's Salon piece about finding the love of his life and simultaneously his muse, got me thinking about the symbiosis between poetry (loosely defined) and the institutionalization of love. The image depicts what looks like a concrete poem, a piece of writing in the shape of its primary subject or theme, emerging from a typewriter. Because of its shape (that of a heart) the viewer cannot help but view the poem as a valentine. The tradition of sending these cards, poems, or epistles to one's sweetheart is as old as the holiday's association with romantic love, dating to the 15th century. The Renaissance cult of courtly love partly explains the origins of this practice. But why do we still turn, on this day, to puns and emblems to celebrate our romantic relationships?

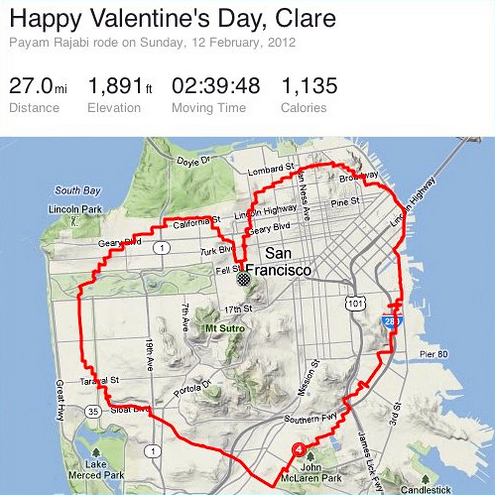

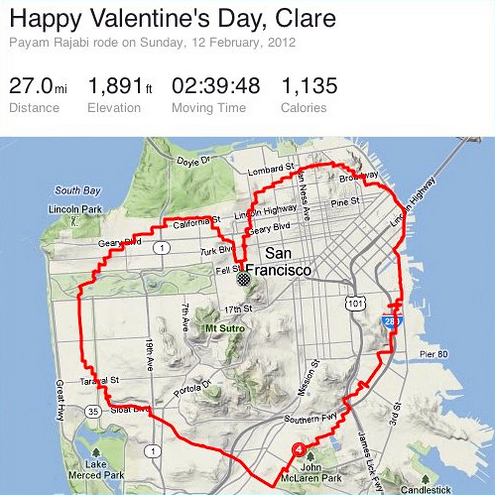

Image Credit: missionbicycle.com

I'm not quite sure, but maybe if we look at another concrete poem of sorts we'll get closer to an answer. Payam Rajabi, the cyclist who sent this valentine to his long-distance girlfriend last year, created it by taking a heart-shaped path through the streets of San Francisco and tracking his route by GPS. The resulting screenshot is a spatial metaphor for his love. The map hyperbolically implies the magnitude of his affection (his love for her is a big as the city); the location evokes romance; and the shape of the route encourages a metonymic relationship between the place, San Francisco, and Rajabi's feelings (in other words, S.F. becomes a kind of shorthand for Rajabi and his deep affection for his girlfriend). Now what kind of boyfriend wouldn't aim to impart all of this on Valentine's Day with a single, poetic gesture? Maybe one who dislikes the idea of biking up Lombard Street.

SF hills aside, I think Rajabi's valentine illustrates that the holiday can serve as a sort of challenge for our wits, a poetic call to arms. For centuries, we have delighted in the challenge of transfering our profoundest feelings into the confines of a little poem or keepsake. As Donne writes of this magic trick, "we'll build in sonnets pretty rooms." Happy Valentine's Day!

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago