Visual literacy, like "cultural literacy," can be thought of as sharing two key characteristics with laguage and literacy. When we call someone "literate" we typically assume that she knows how to read her native language and has a general familiarity with or awareness of significant works in her national/cultural literary tradition. A person demonstrates cultural literacy in the United States at the beginning of the 21st century when, for example, she has seen The Breakfast Club and can tell you that each of the five characters represents a fundamental stereotype of teen-angst movies. In each case, literacy includes 1) a skill set (reading English; watching critically) and 2) a body of knowledge (Hamlet; John Hughes films). In much the same way, visual literacy can be imagined as both HOW we read images and WHAT images we have seen and can regognize. Most Americans, for example, would recognize the flag-raising over Mt. Suribachi on Iwo Jima and identify it as an image of national pride in a military victory.

We should always recognize that literacy represents a continuum and is not a binary opposition in which a person is either literate or illiterate. You may have seen The Breakfast Club but not Pretty in Pink, and you might recognize the Marines on Suribachi without knowing the name of the mountain (or that one of the men was Ira Hayes). The ability to read an image is also not something you have or you dont: essentially everyone can recognize some meaning in an image, and even accomplished image-readers can always improve their skills. As with history, literature, music or chemisty (yes, even natural sciences have literacy), working on one aspect of visual literacy tends to improve the other as well. If I decided to watch more John Hughes movies, I'll probably get better at recognizing typical plot-lines and character develoopment; if I want to be a better reader of Shakespeare, I will need to start reading more plays.

As you can see, no one can be "literate" in general. We are literate in specific languages, mediums, and topics, and literacy often implies a connection to certain cultural, social or national groups. Knowing the intricacies of why Kanye West wrote "Big Brother" for The Notorious B.I.G. would give you a certain amount of credibility among hip-hop fans by signifying that you are part of the group or in the know (the same could be said for knowing that "right-bank" means merlot at a Bordeaux tasting or citing scripture by chapter and verse in a Pentacostal church). As for visual literacy, immediately identifying the comic-book camp of a Lichtenstein painting will signify membership in a different group (Pop Art fans) than recognizing the alternate-away colors of the Seattle Seahawks (NFL fans).

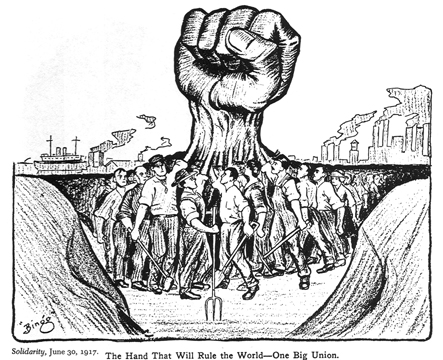

Visual iconography is often tied up in self-formation, group identification and expressing group solidarity. The sea of burnt orange at a University of Texas football game is one example, but solidarity is also expressed through national flags, political emblems and gang tatoos. The twentieth-century return to the "Stars and Bars" in former-Confederate states presents a complex and controversial example of visual iconography making claims about who belongs (and who doesn't belong) in the states that employ the old battle flag. How do we read the move first towards and then away from this most-recognizable symbol of the Confederacy? Who and what do we expect state flags to represent? How does the significance of an image change over time, and how far can symbols be rehabilitated?

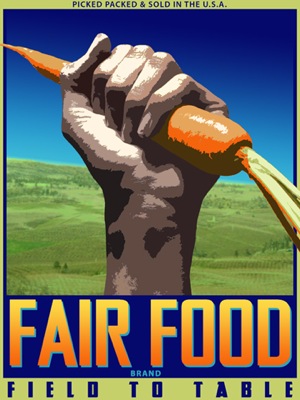

The rising interest in food production and related policy issues at the end of this century's first decade has spawned a wide range of visual icons and image-arguments. Many of these arguments repurpose and redeploy images from earlier social and political movements as a way of writing themselves into a broader history and claiming solidarity with particular groups and movements. They are, in effect, employing images to generate a useable past. They are also reminders that a certain savviness with regard to visual literacy is essential for navigating an image-obsessed democracy.

A phased assignment using food production to explore iconography and group solidarity might have a structure like this:

- Part One: Present students with Oregon-based artist Joe Wirtheim's "The Victory Garden of Tommorrow," an art/propaganda campaign that repurposes twentieth century propaganda for twenty-first century food politics. Have them search for source images on a site like this one and discuss what arguments and sentiments Wirtheim is able to evoke with his retro propaganda posters. WWII features prominently in the collection, but there are also visual references to optimistic atom-age futurism and the modern environmental movement.

- Part Three: Have students research important images from farm and labor movements with which the Fair Food Project might be expressing solidarity (such as "Okie" farmworkers from the Great Depression, Ceasar Chavez's United Farm Workers, or even the Black Power salute at the 1968 Olympics) and write a paper explaining how familarity with those images (a particular visual literacy) determines how we read "Fair Food: Field to Table." Interesting images in this context can be found on sites like Red Scare, Labor Arts, the Library of Congress's online FSA archives, or print sources like Evans's and Agee's Let Us Now Praise Famous Men and Riis's How the Other Half Live. They should think about what groups/movements the project aligns itself with visually (and, by extension, how they position themselves historically) as well as how that use of images attempts to build solidarity with its audience (in other words, how is group identity/history used rhetorically to persuade, build ethos, etc?).

Image Credits: "One Big Union" by Ralph "Bingo" Chaplin and screen capture from FairFoodProject.org

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago