What does it mean to argue the same point in a different way, and how does the argument change when it's visual, not textual?

In this activity I explore this question through four paintings decrying war. Each of them is widely acknowledged among art critics as a seminal anti-war statement, but they're all quite different in their use of emotion and reason to make an argument. This activity works well in a 50-minute class period. I chose four European paintings for the exercise, but an instructor could easily substitute other works of art for these. The exercise works particularly well if you can find art work from different periods so that you can compare and contrast method and historical context even as the themes remain constant.

I have included the paintings below with some of my thoughts on them. Scroll farther down for a description of how to conduct this exercise in class.

Francisco de Goya's "The Second of May 1808" (left) and "The Third of May 1808" (both 1814)

These two paintings stage scenes from the French invasion of Spain during the Peninsular War. In the Romantic tradition, the paintings are highly dramatic, with messy brushstrokes, bold use of light, and lots of emotion in the faces of his subjects. The cost of war is evident here in the mania and violence of "The Second of May" and the terror of "The Third."

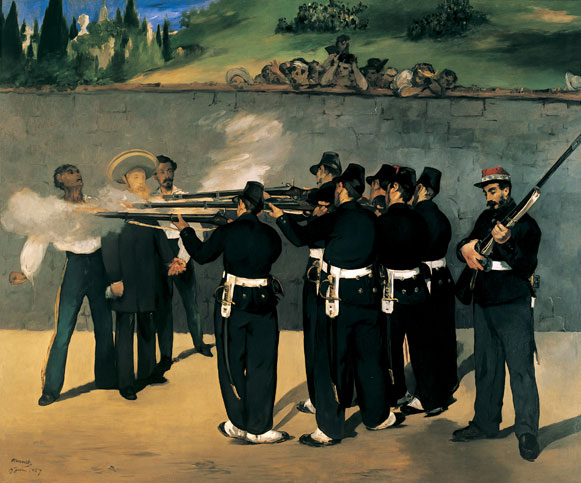

Manet's "The Execution of Maximilian" (1869) depicts men from Benito Juarez's army executing Austrian Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian in Mexico in 1867. An impressionist, Manet is more cool and restrained than his predecessor, Goya, but the influence is clear in both the content and the composition. Here, as in Goya's "The Third of May," the firing line is on the right of the canvas, their backs to us. We can't see the killers, but we do see the victims.

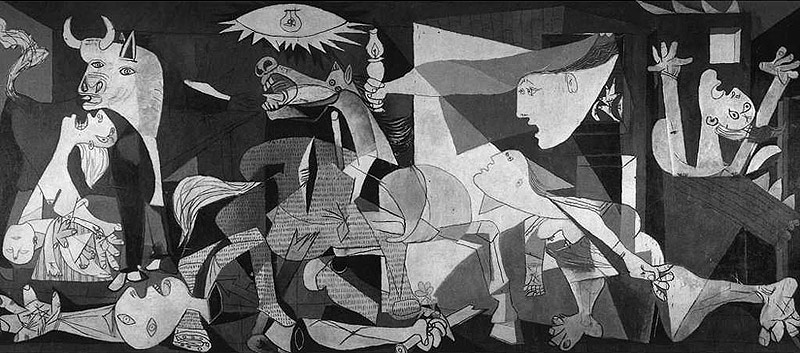

Picasso's "Guernica" (1937) is the least representational of the three paintings. Like the others, it is a response to historical events -- in this case, the Nazi bombing of the Basque town of Guernica (also in 1937). When Picasso completed his canvas, the painting was exhibited at the World's Fair in Paris and brought international attention to the Spanish Civil War. Picasso doesn't use color, as do his predecessors, and his painting doesn't have quite the narrative arc that Goya's and Manet's do. What we see instead is intensely emotional, a visual representation of chaos, destruction, fear, and despair.

The purpose of this exercise is to get students to look at art as argument, but in order to do that the first step is to get them to "close read," so to speak, a painting.

1. Project the Goya painting.

2. Ask students to jot down their impressions on the painting. You might suggest specific elements they should pay attention to: use of light, brushstrokes, composition. Ask them to think of any questions they might have about the historical context of the painting.

3. Have students share their impressions and questions. Once you've heard what they make of the painting without the help of contextualization, fill in the blanks for them, explaining a little bit about Goya as an artist and the historical context of the French invasion.

4. Try to arrive at a group consensus about the painting's argument and method.

5. Repeat for Manet and Picasso, using the later artists to build on the group analysis.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago