[Note: This post contains spoilers, please click on the title to proceed]

Image credit: mbmg-media.com

In her New Yorker piece, “The Closure-Happy ‘Breaking Bad’ finale,” Emily Nussbaum writes, “It’s not that Walt needed to suffer, necessarily, for the show’s finale to be challenging, or original, or meaningful: but Walt succeeded with so little true friction . . . that it felt quite unlike the destabilizing series that I’d been watching for years.”

Nussbaum’s is perhaps the single most concise articulation of a broader theory floating around the internet: that the “happy” ending of “Felina” was a poor fit for the show, which should have otherwise concluded on the same grim note we saw in the second-to-last episode, “Granite State.” And I would beg to differ. It’s not that I disagree that the final episode “Felina” wasn’t “closure happy” – it most certainly was-- but that I think that Nussbaum (though very insightful), and those who take a similar stance, miss the mark in presuming that the finale was somehow incongruous with the rest of the series.

For me, the series has always had a strongly humorous and absurd element (it is, after all, about a high school chemistry teacher turned global meth manufacturer and distributor). That the show ended on a semi-victorious note is perfect, because, as far as I’m concerned, the show is a tragicomedy – a duality strongly reflected in the show’s aesthetics. In T.V. shows, the most common problem tragicomedies run into is that they’re perceived as a bait and switch. You come in for the comedy, and end with a sappy drama. This seems to be what Nussbaum is referring to: a sense that she began watching the show for an edge-of-your-seat nail-biting-ride that should have ended all doom and gloom, but instead got an absurd, perfectly-synchronized ending.

It’s hard to create a successful tragicomedy – the trick seems to be maintaining consistency with the drama without ever losing sight of the comedy. The main way the show kept in touch with its comedic side, even in the midst of serious trauma and dread, was to make the visual elements comic.

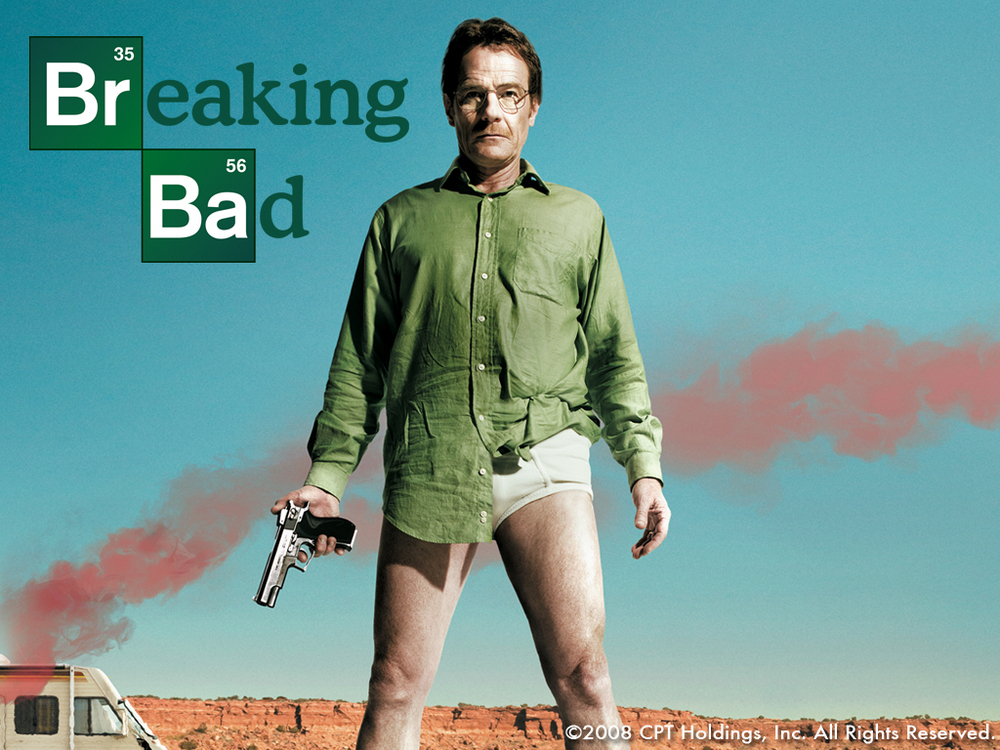

The most obvious and iconic tragicomic shot of the entire series was in the show’s pilot (and used in much of its subsequent advertising). I’m referring, of course, to the image of Walt in his underwear in the Santa Fe desert. To recap: the pilot opens with Walt careening his meth-lab trailer towards a ditch. In a state of animal terror, in his tidy whities, he records a goodbye note to his family via camcorder. It is thanks largely to wardrobe choices, that, despite the panic and violence, there is always a sense of how utterly ridiculous it all is.

In a segment from “Inside “Breaking Bad” which ran on AMC, Vince Gilligan explains that they chose briefs over boxers for this particular scene. “He [Bryan Cranston, the actor playing Walter White] looked more vulnerable wearing them . . .You kind of hope it’ll be one of those iconic images that kind of sums up the show. This kind of everyman character in his suede Wallabe shoes in his underpants and a .45 in his hand ready to take on whatever comes over the rise.”

In other words, a humorous outlet was never waiting in the wings but always embedded, front and center. By calling Walt an “everyman” with a .45 waiting for that thing “over the rise,” Gilligan verbalizes what the picture already shows: Walt as cowboy outlaw. The thing that makes this cowboy aesthetic iconic and interesting is its juxtapositions with the supposedly less macho accoutrement: Wallabes and tidy whities. In my next post I’ll delve deeper into these juxtapositions between the Western desert and the domestic elements, and the relation of the tragicomedy to a sense of completeness. In other words, the aesthetics of finales themselves.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago