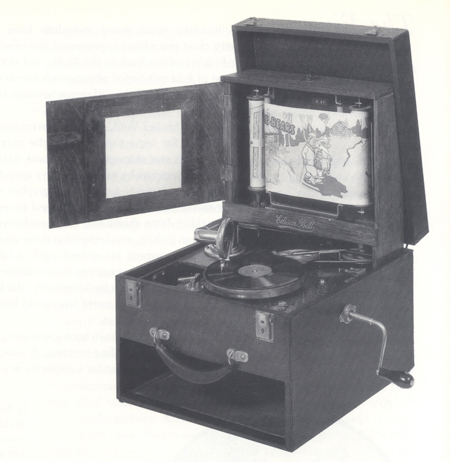

The Edison-Bell picturegram from 1927 (in Sound Recordings). The toy illustrates the convergence of sound and image.

As the budding audio recording industry was creating use value by advertising the phonograph alongside writing machines, pens, pencils, and cameras, another convergence was happening as well. The motion picture industry, which developed concurrently with the audio recording industry, sought to synch up the sights and sounds of the body. Talking, singing, dancing, fighting, and falling had been standard in the motion picture industry since it began, but these bodily acts happened silently on screen. It was only a matter of time before the body would be audible on screen.

The audio-video convergence finally happened in 1927 with "The Jazz Singer," but Thomas Edison had worked on motion picture prototypes (the Kinetoscope and the Kinetograph) forty years prior. And, the convergence was far from complete, total, or perfect. The same year "The Jazz Singer" was released, Edison released another clumsy attempt at combining sound and pictures. According to Peter Copeland in the book Sound Recordings, The Edison-Bell picturegram was "easy to damage and was not a huge success."

The merging of audio recording and moving images represents both a period of convergence and a period of divergence. While phonography, writing, and cinema came together in the production of movies, they also fractured into distinct industries and skill sets. The kinetoscope and the phonograph came out of Edison's Menlo Park lab, but after their invention, motion pictures and audio recording (as well as writing) would increasingly professionalize, specialize, and fracture. In an article version of "Gramophone, Film, Typewriter," Friedrich Kittler writes:

The historical synchronicity of cinema, phonography, and typewriter separated the data flows of optics, acoustics, and writing and rendered them autonomous. The fact of this differentiation is not altered by the recent ability of electric or electronic media to bring them back together and combine them. (113-4)

Even though computer users can now remix audio and video on their laptops—and even though audio recording and movies grew out the same place—optics, acoustics, and writing remain distinct.

It is important to see this prolonged synching of audio and video as both a convergence and a divergence. The convergence speaks to our desire to combine technologies to create environments in which we can access all of our senses and immerse ourselves. But the divergence suggests that optical, acoustic, and written modalities have developed into different industries for good reasons. Different parts of our bodies and brains are activated by different modalities. Different training and skill sets are required for producing visual, aural, and written texts. Different professions have different levels of access to knowledge and skills associated with each modality. And, of course, in terms of universal design, we all have different levels of access to the texts produced with these different modalities. And our levels of access are not fixed. We gain and lose abilities through things like employment, education, and age. As we keep in mind the fact that audio recording has a connection to writing, and to the realm of the visual, we might also consider the value that comes from separating modalities.

Works Cited

Copeland, Peter. Sound Recordings. London: British Library, 1991. Print.

Kittler, Friedrich. "Gramophone, Film, Typewriter." October 41 (Summer 1987): 101-118. Google. Web. 25 July 2011. .

This is the third in a series of blog posts that will explore visual aspects of audio recording technologies. If you enjoyed it, you might read the first post, and second post, too.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago