Image Credit: The Harry Ransom Center

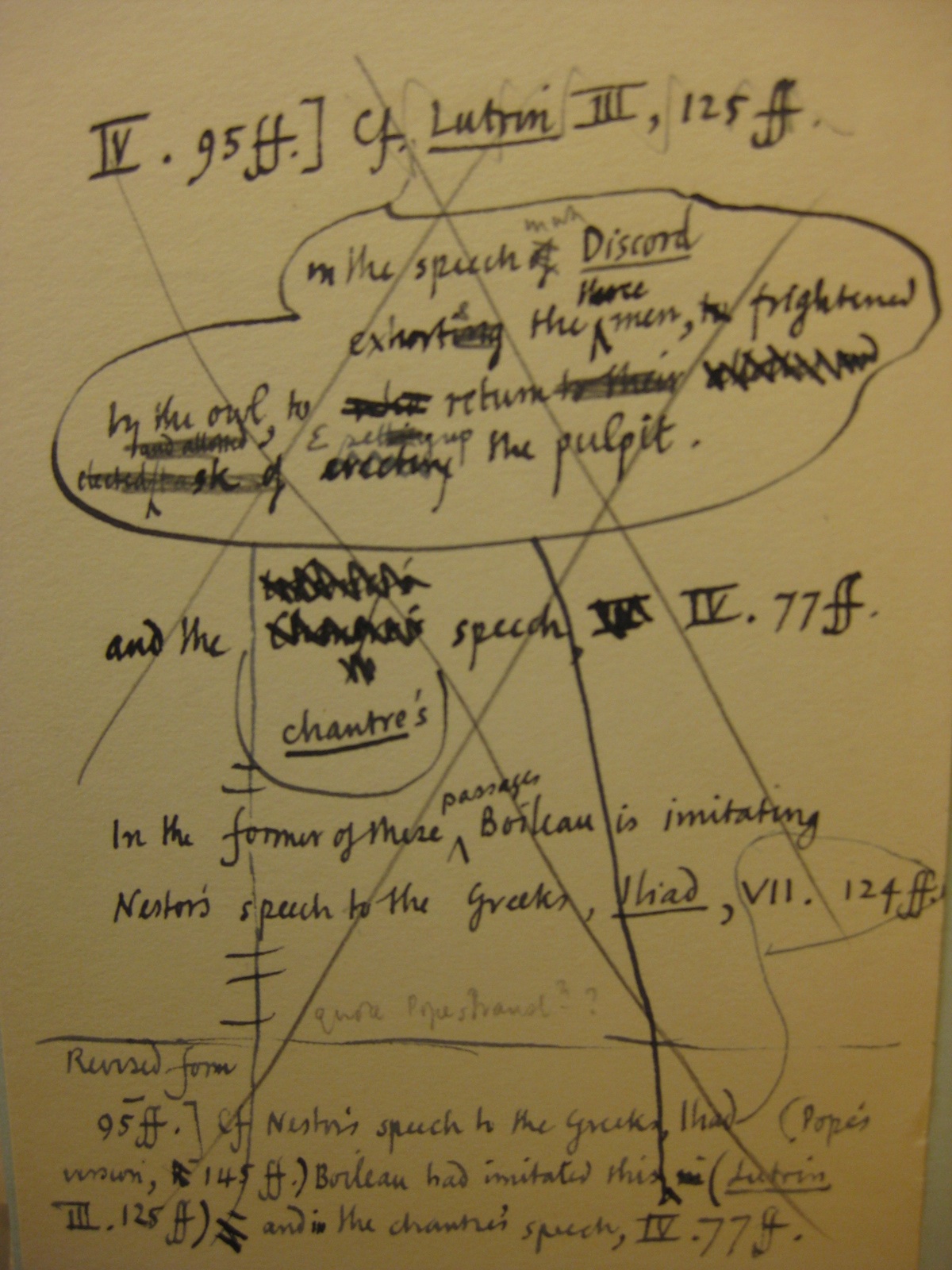

The following post concerns my recent visits to the Hazel H. Ransom Reading Room at the Harry Ransom Center. The images, such as the one above, were derived from unpublished scholarly notes that I never would have found if I didn't use a card catalogue. Since I have been in the process of writing my dissertation in the Department of English Literature, the resources at the Harry Ransom Center have guided me toward avenues of research I did not initially expect to pursue. I would like to relate a personal narrative and a few thoughts about why I’ve enjoyed accessing the Center’s extensive and rich archive by means of the card catalogues. The views expressed below do not reflect those of the Center, but are entirely my own. I do not write from the point of view of a library scientist, although I might gesture toward their expertise in my personal reflections on old-fashioned metadata. Instead, I hope to reassert what many students at the University of Texas already know, concerning the advantage of our proximity to the Harry Ransom Center. Specifically, I would like to suggest the need to actually visit the Reading Room to realize the full extent of the possibilities for research there.

Image Credit: The Harry Ransom Center

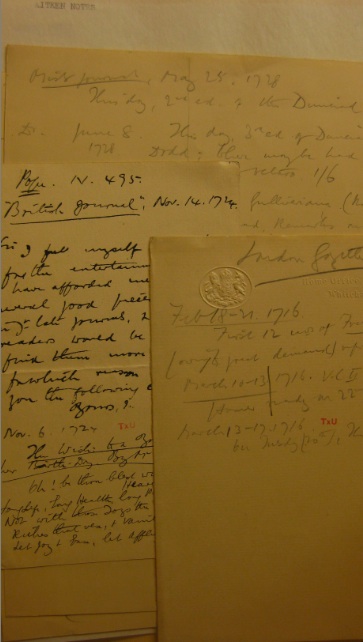

Recently, I came across an exciting discovery after browsing the Harry Ransom Center’s website. This pertained to a trove of over 2,500 books, periodicals, and pamphlets, which Reginald Harvey Griffith donated to the University of Texas at Austin just prior to Dr. Harry Ransom’s founding of the “Humanities Research Center” in 1957. I happened to have known that Griffith taught at the University of Texas during the middle of the twentieth century, and that he shared ties with a group of scholars at Harvard who wrote quite extensively on eighteenth-century “Club” literature (my area of specialization). I was not able to find out what was in Griffith’s archive, however, because this was not listed online. When I visited the Reading Room and inquired as to the materials in the collection, I found out that the contents of this archive were only accessible in three separate card catalogues, marked as “Manuscripts File,” “Provenance File,” and “Collections File.” The staff at the Center was extremely helpful in instructing me as to the significance and intricacies of these card catalogues, as well as the appropriate methods for calling books and manuscripts out of special collections.

Image Credit: The Harry Ransom Center

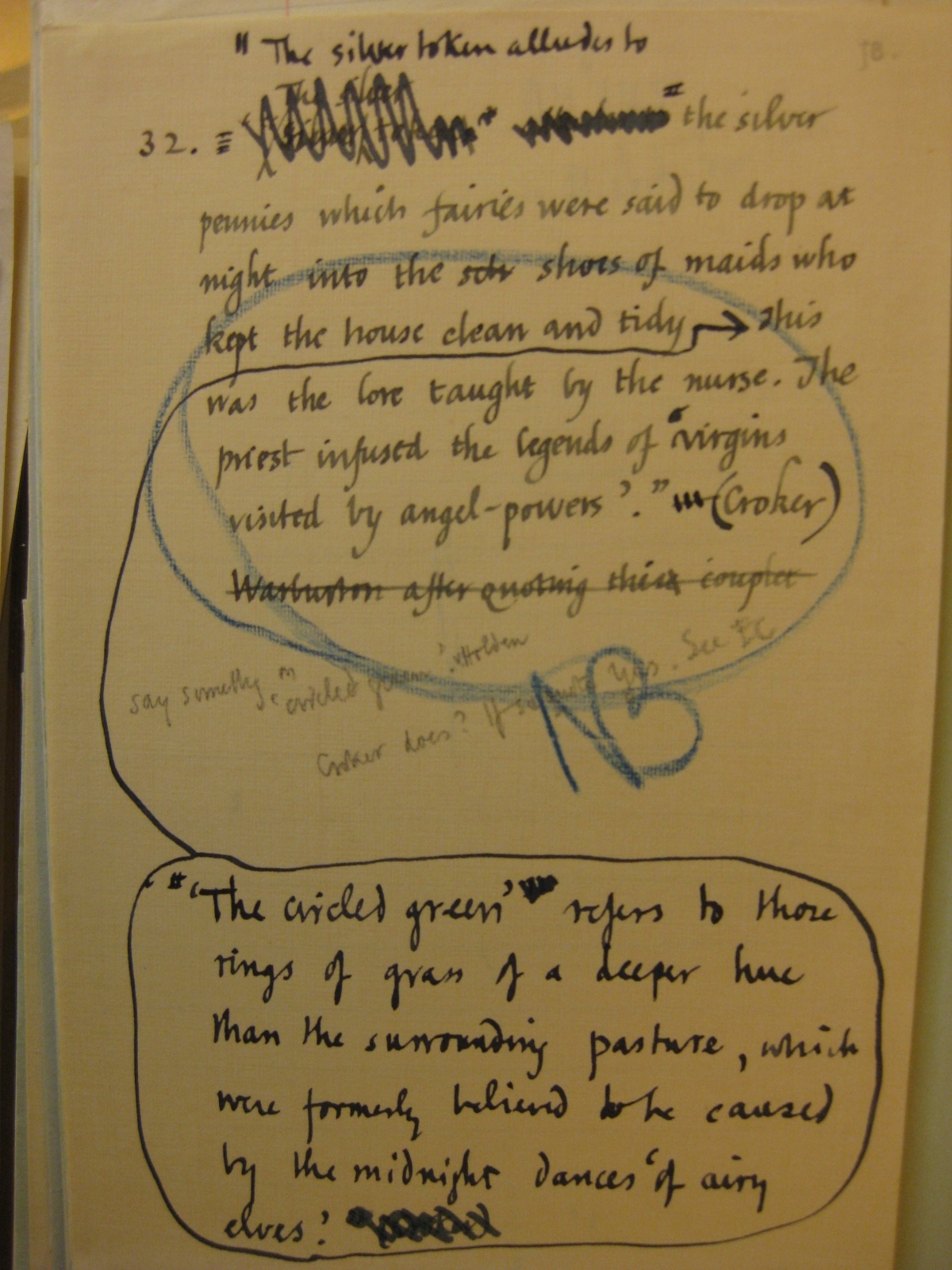

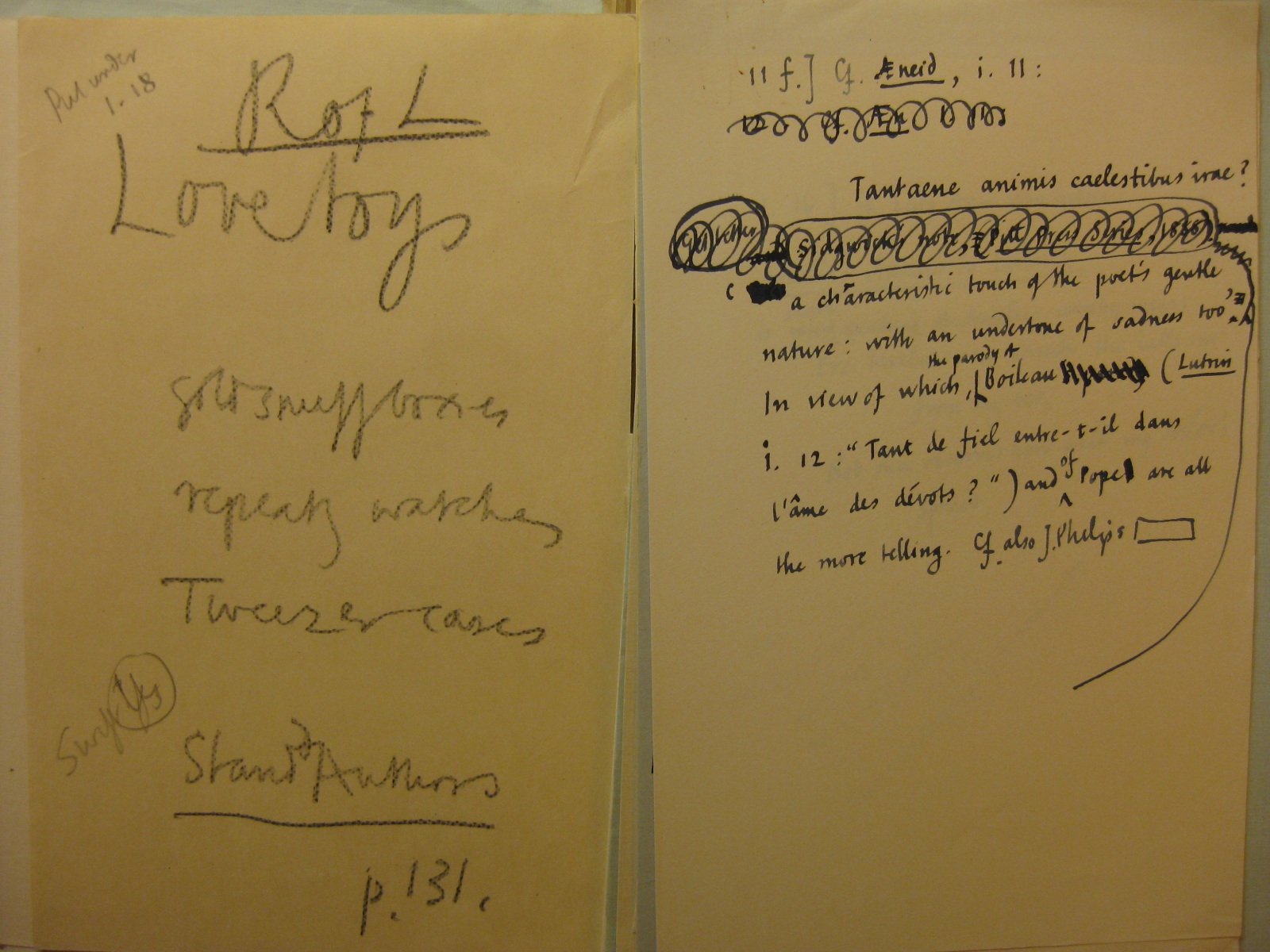

In my initial sweep through the three separate shelves of Griffith’s Collections file, I discovered titles of several 18th centuries texts that I had never before encountered. While sifting through all three separate card catalogues, furthermore, I found cross-listings to other scholars of 18th century literature, whose books and manuscripts I did not know were part of the Center’s holdings. This search eventually led to individual file cards, which revealed their handwritten letters to famous scholars well outside the field of 18th century British literature. Although I entered the reading room with a specific objective in mind, the information in card catalogues led to possibilities I could not have predicted. Studying manuscripts is more time-intensive than reading print, but the documents have a mystique and value for being originals. Below, for instance, is an image of G.A. Aitken’s note for his purchase of Alexander Pope’s The Rape of the Lock.

Image Credit: The Harry Ransom Center

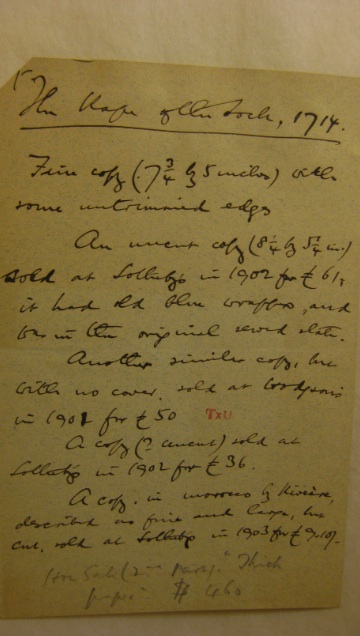

While the Center’s online finding aids are a great place to explore the collections from a distance, search a transcribed catalogue, or view a digitized archive, there is a good deal contained in the actual card catalogues that is not online. Beyond this specific difference, there are others that deserve recognition. For instance, the direct access of online search terms may have a tendency to limit search results, since it often produces a list of just what you’re looking for. Not to say that I don’t cherish online databases or that I could study happily without them, but I also appreciate card catalogues for their capacity to surprise. If card catalogues are not the vanguard, they still have an experimental edge. Have fun with them! I particularly like choosing a given year in the “Dates” catalogue [which organizes the Center’s collections in chronological order (typically yearly)], and seeing what’s there. Another option (which I haven’t tried it yet) might be to explore the “Publisher’s” catalogue in some similarly open-ended fashion. These games will pass the time while you’re waiting for your books to arrive. My point is that card catalogues aren’t restricted to Luddites only, and the combination of old-fashioned adventurism and the wireless internet can be a powerful one. This argument goes deeper than simply looking at old editions of books, but it involves an entire procedure of seeking them out in the first place. As online research increases in speed, immediacy, and (seeming) transparency, even advanced students may feel the urge to scoff or cringe at the thought of long narrow boxes and rectangular typewritten index cards. Writing from personal experience, I can say that card catalogues have their own charm and usefulness.

Image Credit: The Harry Ransom Center

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago