Image Credit: Per Erik Strandberg

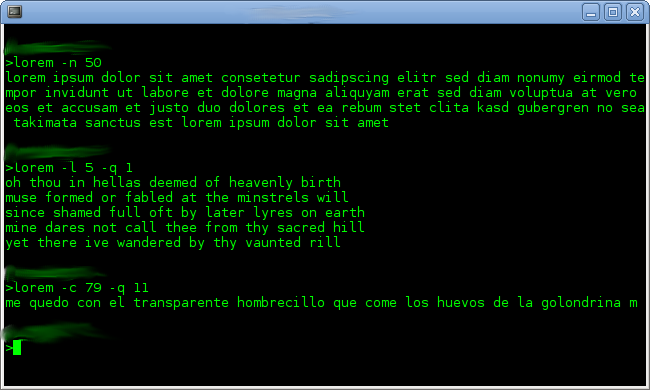

“Lorem ipsum” has been recognized by publishers and graphic designers throughout the 20th century as the industry standard text by which to mock up text layout, thanks to a small UK company called Letraset, which mass-manufactured dry transferrable lettering from the 1960s to the 1990s. With the advent of digital media and desktop publishing, the first two words of the ubiquitous sequence have become recognizable to the population at large. It appears in markup templates almost universally across publishing platforms. Templates in word processing, presentation software, and web design all bear the mark of their print forbearers. Thus, lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, a scrambled copy of an excerpt from Cicero’s De finibus bonorum et malorum (“of the ends of good and evil”) has entered into popular discourse as a recognizable placeholder, as Wikipedia says, “used to demonstrate the graphics elements of a document or visual presentation…by removing the distraction of meaningful content.”

This post would like to explore lorem ipsum as an ideological concept in both print and digital media. In part, this exploration will question what it means to view text itself as visual rhetoric. How can text draw attention to or defer attention from itself as a visual object? How can conventions of representation make text, like lorem ipsum, disappear? Might we view such disappearance as a sort of censorship? If so, how can we describe the internal logic of such censorship as an ideological trend in the digital age?

Lorem ipsum corresponds to a larger concept in mass media—that of transparency and immediacy. According to Bolter and Grusin’s Remediation, modern society exhibits a dual impulse regarding media representation. On the one hand, audiences demand multimodal approaches (the multiplication of medium), but they also demand hyperrealistic representation. In such hyperrealistic representations, the medium becomes transparent, delivering the message it carries with as little perceivable mediation as possible. “Our culture,” Bolter and Grusin argue, “ideally…wants to erase its media in the very act of multiplying them.” Society’s demand for “invisible” mediation leads to medium transparency and immediacy—the medium delivers an object that seems immediately present because the medium focuses attention on the object, not the delivery of that object. Virtual reality, hyperrealism in film, and reality television are all examples of immediacy because the medium’s internal logic “dictates that the medium itself should disappear,” condensing the distance between the imagined and the real.

Lorem ipsum itself represents a conundrum, because as a text, it exhibits transparent qualities. But this strategy is designed to draw attention to the medium in which it appears—the very opposite of the relationship Bolter and Grusin describe between hypermediation and immediacy in Remediation. In the case of text as a visual object, then, we must amend the terms Bolter and Grusin give us to account for text as a form of mediation. When text appears contentless, it calls attention to the medium that contains it, rather than to itself. This relationship denies text as a medium in itself, rendering it an object of visual rhetoric used to display the mediating power of the medium in which it appears.

What ideological corollaries to the concept of lorem ipsum can we identify and digital and print media? Where can we see this phenomenon replicated? One clear example is in internet advertising. As we read, we consistently “filter out” the content of advertisements using recognizable advertisement form, interpreting the object only as an “ad” without paying any attention to its content. Take, for instance, this example:

Image Credit: Screencapture from CNN.com, as captured by LT

Because audiences familiar with current modes of internet advertising have become accustomed to the disruptive ad, in most cases they feel the immediate impulse to “skip” or exit the ad. The same is true of timed advertisment—attention is more likey to be placed on the “skip ad” countdown than on the advertisement itself, even as it briefly forces itself upon the viewer.

Image Credit: Screen capture from Youtube, as captured by LT.

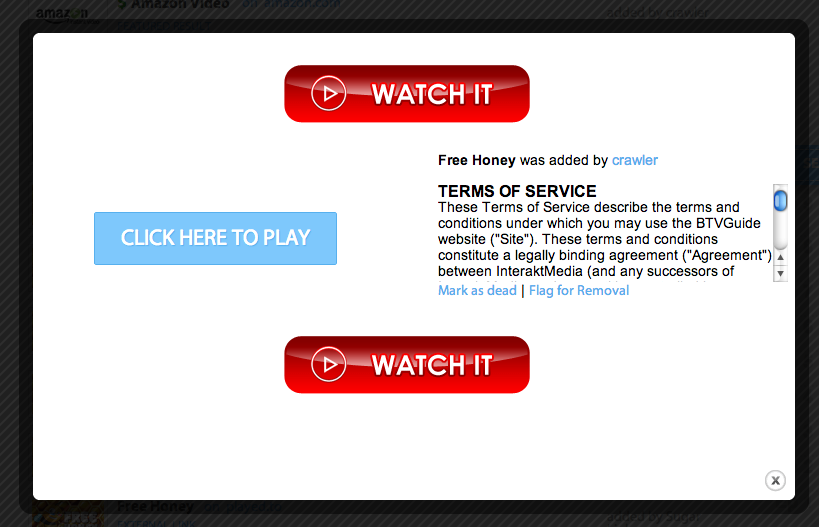

Streaming sites abound with a manipulation of this effect, disguising advertising with the mask of what the viewer is actually looking for. As consumers adapt to strategies implemented by ad produces and producers revise their strategies according to those adaptations, the boundaries between advertising, entertainment, and news media blur considerably. Which of these, for instance, represents the actual link to download the desired object?

What arises is a form of self-censorship. Audiences constantly filter their line of vision, giving attention to what they are looking for and ignoring or willing transparent the constant web of distraction that surrounds it. Perhaps this—the interpretation of a media object as unimportant or ignorable—has always been the most insidious form of censorship.

As Bolter and Grusin point out, the 20th century has no monopoly on hypermediation. 18th century print culture exhibited a mass market that demanded consumers make calculated choices about what they consumed; these choices multiplied exponentially in the 19th century. But never before has hypermediation existed across so many media simultaneously, making a transition between self-“filter bubble”-censorship and external censorship, whether on moral, political, or ethical grounds, possible.

I would like to suggest that we can see examples of this external censorship capitalizing on established, cognition-oriented modes of self-censorship in play in multiple arenas. For example, Managing Director of the Mormon Family and Church History Department Richard Turley responded to John Krakauer's controversial investigation of violence in the Mormon faith in Under the Banner of Heaven by arguing that "...[a]lthough the book may appeal to gullible persons who rise to such bait like trout to a fly hook, serious readers who want to understand Latter-day Saints and their history need not waste their time on it." Here, Turley criticizes Krakauer's book using language that differentiates the elite, skeptical, knowledgable reader from ordinary mass-readership (for him, "gullible persons"), and, by such a logic, condemns Krakauer's text for its content by means of its medium; that is, pop journalism. In this portion of his critique, he censors by rendering the text itself irrelevent or, perhaps, invisible.

This highlights a larger trend in modern acts of censorship, broadly defined: popular culture is often degraded as not worthy of attention due to its mass appeal and ordinary audience. The most effective critiques of mass-market literature, such as the Twilight series and Fifty Shades of Gray, for instance, often hang a banner above these works declaring them “unworthy of attention” rather than immoral or distasteful; the latter labels often prove to evoke more, rather than less, interest in a work, whereas declaring them “wastes of time” has a greater affect on deterring particular readers.

As literary or media scholars we tend to exhibit great skepticism toward censorship that denies audiences the ability to, to put it simply, “think for themselves.” We decry modes of censorship that oppose audience agency in negotiating semiotic systems and cultural, ethical, or moral codes. We should, then, be equally vigilant against this “lorem ipsum” censorship. It is a censorship that attempts to ascribe and emphasize medium (that popular culture is synonymous with discardable literature; that challenges which question the terms of an argument exist outside the realm of civil discourse) at the expense of content; it asks us to interpret text itself as transparent; contentless; uninteresting. Such arguments ask us to ignore “the man behind the curtain,” rather than blindly opposing him; it is these arguments that may be the most dangerous of all.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago