Site informationRecent Blog Posts

Blog Roll

|

A Posthuman Selfie?

Submitted by Sarah G. Sussman on Fri, 2014-02-21 13:51

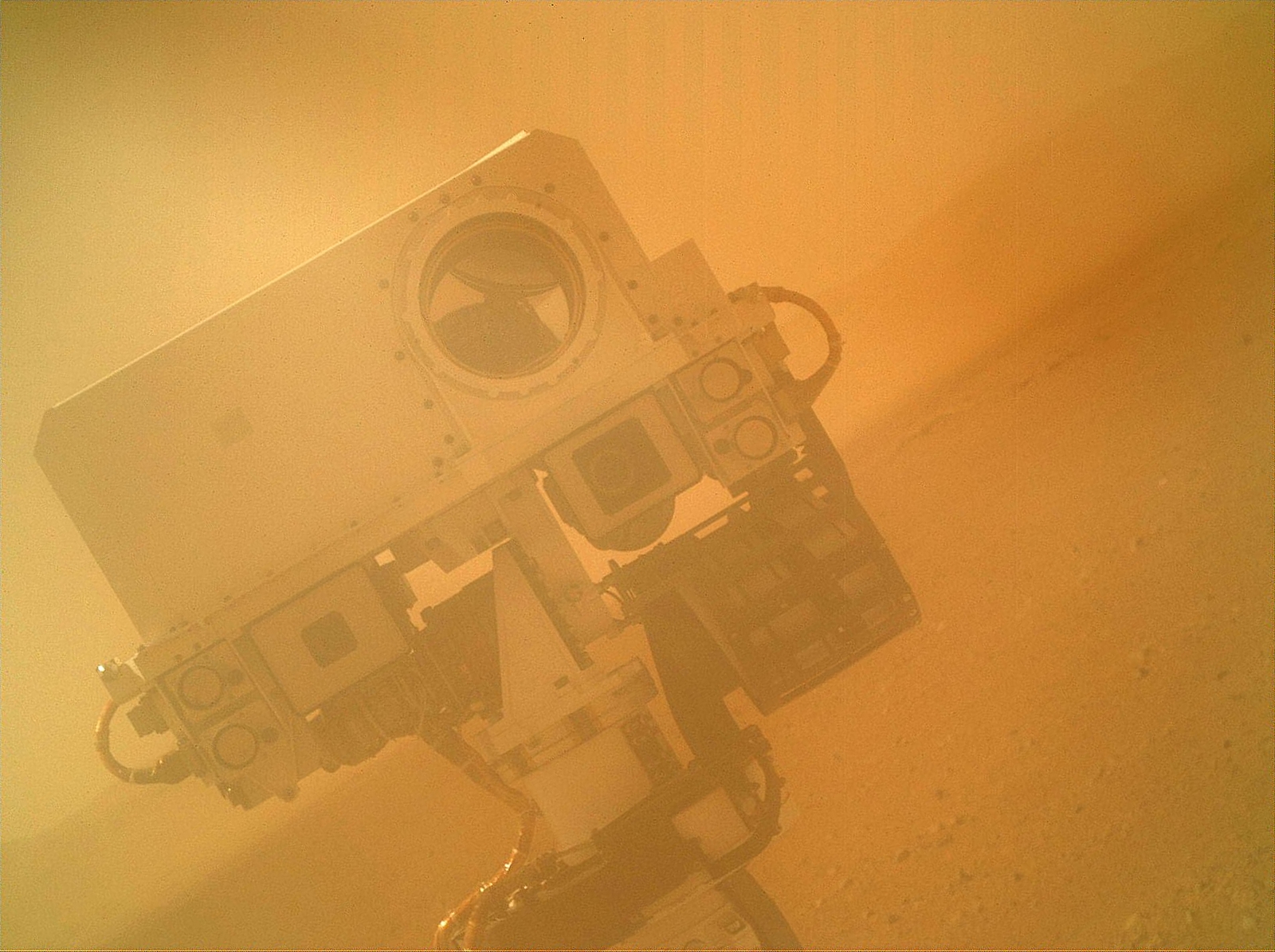

Image credit: Wikipedia, Mars Curiosity Rover's first selfie In my last post, I recounted a history of some of the most iconic images of space which primed my reaction to the Mars Rover’s portrait of Earth. This led me to offer a short curation of ways key figures have pathologized space, and their eco-critical views of space inflected by Earth, but all of this talk of Earth as “home” begs another question: If photos of Earth from space are photos of a shared home, are they a kind of self-portrait? More importantly, if robots are taking these images, are these self-portraits of humanity, or something posthuman? Lastly, why do those rovers have to be so darn cute? Mid-century space travel always carried within it a dualistic contradiction between humanism and posthumanism. The lunar landing was “One small step for man, one giant leap for mankind” – a famous verbal flub from what should have been “One small step for a man” – the omission of that article was fitting though, as conversations with space are always attended by a complex collectivism. The lunar landing was an achievement for the human species as a whole, ironically underscored by the competition of the Space Race between the U.S.S.R. and the U.S.A. during the Cold War. Always parallel to this myth of human collectivism was the philosophy of “Spaceship Earth." The “Spaceship Earth” philosophy suggested improved life through a decentering of the human subject. Although the concept of the “Spaceship Earth” dates back to Henry George’s 1879 Progress and Poverty, the idea gained most momentum mid-century when it was taken up by urban planners, activists, and politicians. Notable proponents of the “Spaceship Earth” worldview, like Buckminster Fuller, thought humans might have a better chance at preserving our natural resources if we conceived of ourselves as a planetary collective. In other words, “Spaceship Earth” suggests an inter-special worldview—the broadest collectivism possible. Today, the human endeavors to reach space are often a mix of parody and tragedy that seem to come from the fallout of this posthuman philosophy. Perhaps some have privately entertained this tragicomic vision of space, but I’m interested in the public face of space travel: Nasa’s tweets, movies like Gravity, Neil De Grasse Tyson’s podcasts – which increasingly show space as an existential blend of the grim, the absurdly moving, and finally, the outright comical.

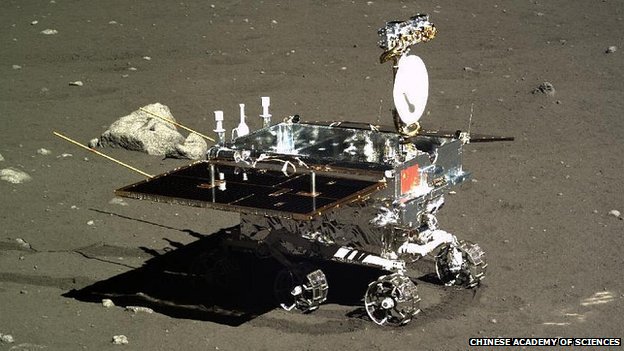

Image credit: NPR.org Yutu Rover China’s Yutu Rover, which recently live blogged its own death, offers a striking example of this affecting absurdity. Perhaps the cutest rover in space, Yutu was named after the pet rabbit of a Chinese Goddess who lived on the moon, Chang’e (Chang’e 3 was the name of the lander who deposited the little rover on the moon). Yutu’s primary mission was meant to last three months (three or four lunar nights) but because of a mechanical malfunction, he was unable to hibernate and thus, unable to preserve enough energy to make it through the lunar night. Via the state-run Xinhua news agency, he writes, "[Chang'e] doesn’t know about my problems yet. If I can’t be fixed, everyone please comfort her. . . This is space exploration; the danger comes with its beauty. I am but a tiny dot in the vast picture of mankind’s adventure in space . . . The sun has fallen, and the temperature is dropping so quickly… to tell you all a secret, I don’t feel that sad. I was just in my own adventure story – and like every hero, I encountered a small problem. Goodnight, Earth, Goodnight, humanity." In space, any expression of emotion seems sentimental, and is open into the echo chamber of the internet where, in some corners, it may coalesce towards a certain gravitas of existential meaning. In this passage, Yutu pays homage to Sagan’s Pale Blue Dot “I am but a tiny dot,” and also calls upon a mid-century Joseph Capbell's monomyth, or hero's journey archetype with the remark "I was just in my own adventure story - and like every hero, I encountered a small problem." It would seem that even robots from China can’t step outside the mid-century frame built by Carl Sagan, myth critics, and others. Or can they? The Mars Curiosity Rover’s live tweets of his journey on the red planet have been equally self-aware, but far more whimsical and comical. Two days ago he posted a selfie of his own shadow with a paraphrase from the band Queen “I see a little silhouette of a rover. (Scaramouche! Scaramouche! No fandango.) Check out my new moves. ” Since taking the first selfie on another planet on September 7, 2012, Curiosity has been dubbed the “King of Selfies.” In 2013, when the Oxford English Dictionary named “selfie” the word of the year, Curiosity tweeted that she was “an illustration” for the word of the year. What does it mean for a machine to gaze into itself? The Curiosity rover’s self-portrait is fascinating in that it offers an infinite regress. These rovers tweets and self portraits mark an existential loneliness and are simultaneously a testament to the kind of metaphysical infinite regress we humans are trapped in, in our tendency to anthropomorphize everything. These rovers are undeniably very funny and cute, but the suggestion that these portraits might in some way be posthuman is countered by the fact that robots are rigged by human operators, and even when these robots take snapshots of the Earth, they are always guided by human programmed algorithms or commands. The resulting images are framed by captions written by NASA. Moreover, it is important to note that these captions are calculate for maximum cuteness. Can it be any coincidence that our expanded dependence on social media is coupled with adorable Lolcats and that even Yutu is a rabbit (what cuter creature is there?). As we reach further into the disturbing vastness of space, rovers seem to become equally more charming, their creators and the public rush in to preserve the reassuring illusion of warmth. The Mars Curiosity Rover’s braggadocious swagger “Check out my moves” or, “look back in wonder!” and his many selfies, are of course calculated by human creators. The latest pathologizing of space apes our internet patois for a reason. As we make space cute, we also make it feel more like home. Still, does that make it less human, or are we merely working out our anxieties as we approach a posthuman age? The Lolcat and other cuddly internet creatures are deceptively complex. Their humorousness derives from their simplicity – they offer relief from more serious subjects. See memes like “pomo cats,” or “The Discourse on the Otter,” on Tumblr, whose very humor function upon the exploitation of the psychoanalytic view that humor functions to relieve tension. Along those lines, one might suggest that these precocious rovers amuse because they offer a diversion from the unknown. |

viz.

Visual Rhetoric - Visual Culture - Pedagogy

Site informationRecent Blog Posts

|

A Posthuman Selfie? |

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago