Site informationRecent Blog Posts

Blog Roll

|

Negotiating Modesty: Reading Mormon Fashion Blogs as Visual Rhetoric

Submitted by Laura Thain on Mon, 2012-11-19 19:22

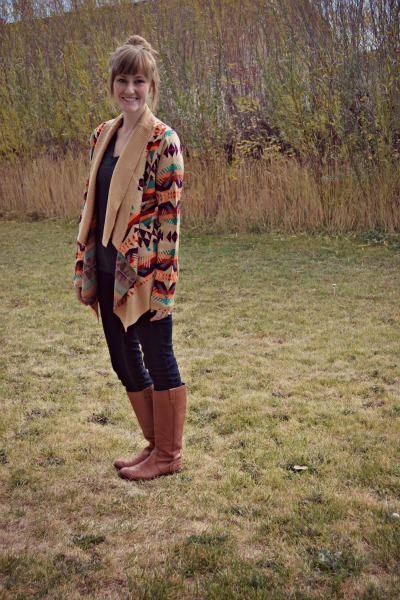

Image Source: Clothed Much Fashion blogs have proliferated the internet since its inception; the rhetoric of the genre is as multifaceted as its participants, most of whom are women. Daily fashion blogging, in which the blogger takes regular photos of the outfit she assembles each morning, is a popular iteration of the genre. Obviously much of the blogger’s value systems is exhibited through the personal ethos she cultivates on these blogs; the way the blogger frames the narrative of the outfit in terms of its relationship to her day-to-day activities reveals much about these value systems, as well. An interesting subculture has received a substantial amount of attention in the fashion blogging community recently, and that is modesty blogging. All the modesty blogs I’ve come across are motivated by religious restriction; the vast majority of these base their definitions of modest clothing upon the tenets of the Mormon church. Of course, the situated ethos of modesty blogging must negotiate an inherent contradiction between two competing definitions of modest: the function of modest dress as a physical representation of religious belief and the concept of modesty as the quality of being unassuming, scrupulous, and free from presumption. What does it mean to take pride in modest dress, to wear it as a badge of individualism and difference? And how can we read these modesty blogs in terms of visual culture? Join me as I take you on a journey into another strange corner of the internet: Mormon fashion blogging.

Image Source: Cats and Cardigans We might make a few generalizations about popular fashion blogs: most successful blogs attract their audiences with an ethos that exhibits an internally consistent personal style (what we might call a “style narrative”) that is accomplished by innovative pairings. Thus, the blog initially attracts an audience with the familiar—a “style narrative” of, for example, grunge, retro, hipster, or editorial—and keeps their interest with the unfamiliar—a scarf made into a bolero or a vintage headband woven into a punk outfit. We might, then, loosely read the ethos of these blogs as “text” in terms of Barthes’ conforming/cutting edge dichotomy in The Pleasure of the Text. This makes the case of modesty fashion blogs especially interesting, because the “cutting edge” component of these blog’s ethos is, in fact, a conservative reaction to counterculture—it operates on the fantasy of return to a dress standard of the past (although its location in the past is certainly ambiguous). The familiar, plagiarizing edge is, in fact, the way that these modesty blogs attempt to participate in mainstream discourse—a discourse that is often countercultural (hipster, grunge, retro). Their popularity comes in large part from the way these blogs resemble in their formal elements many other successful fashion blogs, but are able to translate their audience’s desire for surprise and innovation into a restricted code of dress.

Image Source: Cotton and Curls Most Mormon fashion blogs define immodest clothing as anything low-cut, sleeveless, backless, or too short—some combine a series of positive descriptions along with the negative (for instance “long skirts” or “skirts below the knee” rather than “no skirts above the knee”). Most do not address fit but instead warn against “revealing” clothing. Concrete restrictions almost always regard coverage, rather than the tightness or fit of clothing. This ethos in general is oriented around fulfilling a minimum requirement of modesty, and the boundary of that minimum requirement is represented physically by the temple garment, an undergarment standardized and manufactured by the central Church. Women begin wearing this garment daily when they receive their endowment, which for most coincides with their marriage. We can reasonably assume that most of these bloggers wear temple garments, as they advertise their status as Temple-married women, but it is worth mentioning that almost none of these bloggers mention the temple garment or the way it might restrict their code of dress; rather, these women speak of their restricted dress as a lifelong commitment predating their temple endowment, and a code of modesty that is self-defined and self-enforced. (Many of these blogs begin their "about me" with some variation of “Modesty means ____ to me…”). The deferral of the issue of temple garments is not only a reflection of their sacred status among church members (it is in general considered inappropriate to speak about temple garments to non-members, and is considered offensive to display visual representations of them)—it is also indicative of these women attempting to find a place in mainstream fashion discourse; to not be noticed for their wardrobe restriction but for their good sense of style. The rhetoric of these blogs might be condensed as such: “I am reflecting an internal commitment to God in my physical appearance, but I do this so well that you would not notice unless I told you explicitly.” This rhetorical mechanism seems to operate to ease the tension between competing modesty discourses I have outlined above: these bloggers can take personal, inner pride in their commitment to modesty without bringing attention to their difference (and thus translating pride of self into the public sphere). Counterintuitively, this is accomplished by assimilating successfully into the fashionable discourse of the mainstream.

Image Source: wearing it on my sleeves But there is a way in which this attitude can be read as subversive in terms of Church doctrine, especially when one considers the history of sumptuary laws in the Mormon Church. (There is a useful article in the Mormon periodical Dialogue that outlines the subject in more detail.) Though we might imagine the discourse on modesty to call back to the conservativism of the Einsenhower era, this is not the locus of the nostalgia for modest behavior—it is, in fact, its origin. The first explicit call to modest dress occured in 1951, when Church authority Spencer W. Kimball extolled young, unmarried Mormon women to distinguish themselves from their non-member peers explicitly through a more conservative code of dress: "There is no reason why women need to wear a low-cut or otherwise revealing gown just because it is the worldly style. We can create a style of our own." It is important to note that this address, given at a BYU devotional, was aimed mostly at unmarried young women. As Kimball argues, "We knew of one mother who remonstrated with her lovely daughter who intended to buy a modest evening gown. The mother pleaded: 'Darling, now is the time to show your pretty shoulders and back and neck. When you are married in the temple that will be time enough to begin wearing conservative clothes.' What can be expected of the new generation if the mothers lead their own offspring from the path of right?...The fellows could show courage and good judgment if they encouraged their young women friends to wear modest clothing. If a young man would not date a young woman who is improperly clothed, the style would change very soon." Kimball assumes that women who are married are already living the law of modesty because of the nature of their temple garments; here, as in most of the discourse that follows, the concern is that unmarried women might delay that sense of responsibility until after they take their temple vows. The loose standards that Kimball sets out are a reaction against, rather than a return to, the styles of the 1950s—in fact, his distaste for revealing clothing resembles a return to the fashion of the 1910s, before hemlines were raised and bustlines lowered in the so-called Roaring 20s. And it is certainly of some significance that Kimball himself experienced adolescence in the 1910s—he is demanding, to some extent, a return to the conceptions of modesty that existed during his own days of courtship. Yet Kimball’s call to arms is all very general. The restrictions that modesty fashion bloggers set out above—specific prohibitions against revealing this part of the body or that—are simply not extant in this early discourse. In fact, the next significant prohibitions against immodesty among LDS youth are even less specific than Kimball’s address above. Let us examine the 1965 iteration of a pamphlet still published today called “For The Strength of Youth,” which serves to outline the standards which young Mormons are expected to uphold. Image Credit: Barncow

Image Credit: Barncow Note the text’s deferral of specific criteria (“it is difficult to make an over-all statement concerning modest standards of dress, because modesty cannot be determined by inches or fit since that which looks modest on one person may not be so on another…”). Instead, the text chooses to deliberately define modesty against the standards of the countercultural movements of the 1960s. It warns against “grubby” fashion, implores women to maintain traditional mores of femininity in their dress, and considers androgyny to be the greatest threat to the modesty of young women.

Image Credit: Barncow The pamphlet also extols young women to “dress to enhance their natural beauty and femininity…Few girls or women ever look well in backless or strapless dresses. Such styles often make the figure look ungainly or large, or they show the bony structures of the body…Clothes should be comfortable and attractive without calling attention [to the body].” It is also careful to warn women against wearing pants outside of athletic activity: “Pants…are not desirable attire for shopping, at school, in the library, in cafeterias or restaurants.” Thus we can see that in the 1960s, second-wave feminism and androgynous dress were the chief modes of discourse that the Church set to dress its women against. The letter of the law in these pamphlets is far less respected than the spirit of the law, and the “law” is an attractive but non-sexualized, and therefore sanitized, femininity. Counterculture was at the top of the immodest hierarchy.

Image Source: Haircut and General Attitude Not so today. Mormon women increasingly define modesty in terms of explicit clothing guidelines (inseam lengths, coverage) rather than cultural association; no longer is clothing a statement of conservative reaction to the styles of counterculture but instead a playful interpretation of them. Cultural associates of modes of dress cease to be called into question within this dialogue; instead, the temple garment becomes the silent marker of how much skin is “too much.” Anything that covers these undergarments constitutes modest dress. I see the discourse on modesty in the present day taking place, then, in two separate spheres. On the one hand, church-sanctioned periodicals continue to emphasize the function of modesty as a marker of difference against counterculture, although this is a trope that has all but lost its meaning. Meanwhile, fashionable young Mormon women often embrace an identity that is countercultural—they embrace their ability to participate in cutting-edge fashion while still adhering to the explicit restrictions of their faith. It seems to me that one significant effect of this is, in fact, a return, in a sense, to Kimball’s initial exortations to unmarried women. To the insider Mormon community, these young married bloggers are in a sense instructing their younger or unmarried peers how to live the letter of the law of modesty before they take their temple vows and don their temple garments. For the fashion blogging audience at large, these women express their identity through their commitment to modesty by showing how easily the rhetoric of modesty can fit into the tenets of mainstream fashion; the commitment to coverage exists as a challenge or unexpected element in this endeavor that only enhances their ethos, rather than undermining it, in the mainstream. Modesty then ultimately exists as a function of creativity rather than restriction. And though most of these women are probably unaware of the complex rhetorical history that makes such an ethos possible, they are nonetheless operating in a space in which the definition of modesty has drastically shifted over time, making it possible for these women to, as Benjamin Franklin might say, take pride in their humility—to have no reservations in being immodest in demeanor about their modesty in dress. I will at the very least claim this: that the function of modesty as difference has taken a countercultural turn, and, if a woman being refused entry to a BYU testing center for wearing skinny jeans is any indication, the rhetoric of modesty within the Mormon community is very much a battleground in which the rules of engagement are still being hammered out.

|

viz.

Visual Rhetoric - Visual Culture - Pedagogy

Site informationRecent Blog Posts

|

Negotiating Modesty: Reading Mormon Fashion Blogs as Visual Rhetoric |

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago