Image Credit: SliceofGreen

In anticipation of the Harry Ransom Center’s upcoming exhibition of Norman Bel Geddes’s futuristic designs, I’ve become completely fascinated with the work of a man whom the Ransom Center describes as “an innovative stage and industrial designer, futurist, and urban planner who, more than any designer of his era, created and promoted a dynamic vision of the future—streamlined, technocratic, and optimistic.” This week, instead of focusing on the futurescapes of Bel Geddes after 1927 (the year Bel Geddes launched his industrial-design career), I will discuss a lesser-known Bel Geddes—the man as a father who built fantastic doll houses for his daughters. This man was a big dreamer (per French philosopher Gaston Bachelard, whom we’ll meet later in this post), one who dealt in miniatures.

In the Ransom Center’s finding aid for the “Norman Bel Geddes Theater and Industrial Design Papers” housed at the Center, I found an interestingly domestic reference—one for a “Doll House for Joan.” In this helpful finding aid, I learned that Bel Geddes sketched and drafted the doll house just as he would any architectural or urban plan. Even elevations—though on a miniature scale—were noted! Bel Geddes made this detailed doll house for one of his two daughters, Joan, sometime in the early 1920s. I’m fascinated to see that before Bel Geddes decided to shift gears from stage design for theater and film, he tried out some of his nascent architectural skills with a miniature structure. I’d like to think that Bel Geddes’s ambitions to become an architect and planner were encased in his building a doll house.

Image Credit: Libraryland

Gaston Bachelard might agree with me. In The Poetics of Space (his magnum opus published in France in 1958), Bachelard muses about our relationships with “intimate places,” from childhood homes to closed drawers. His chapters weave poetry and personal experiences with dreams. The chapter most applicable to today’s discussion of Bel Geddes’s doll house is the one titled, simply, “Miniature.” In this chapter, Bachelard uses Poe and Rimbaud to discuss the power of miniatures in our everyday lives. The most wonderful thing about miniatures, according to Bachelard, is that “Values become engulfed in miniature, and miniature causes men to dream.” What’s important about miniatures isn’t their intricacy nor their accurate representation of reality. For Bachelard, “the minuscule, a narrow gate, opens up an entire world. The details of a thing can be the sign of a new world which, like all worlds, contains the attributes of greatness . . . Miniature is one of the refuges of greatness.” The ‘big’ (in terms of ideas, aspirations, and dreams) is encased in the ‘small’ (in terms of size, scale, and material).

Image Credit: The Harry Ransom Center

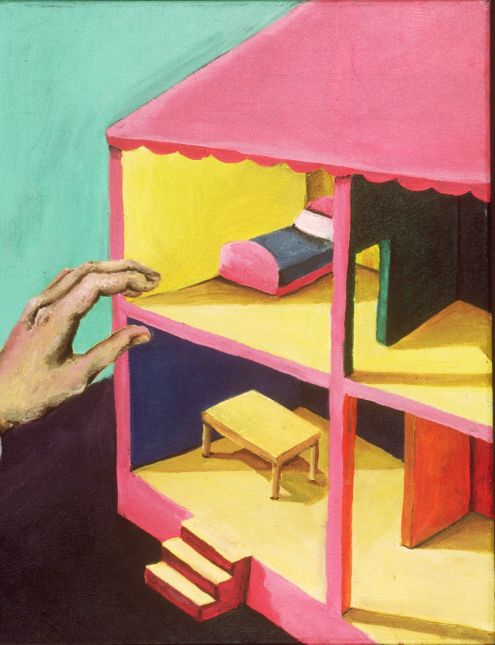

I see glimmers of Bel Geddes’s future in his doll house from the 1920s. The structure is taller than it is wide (a nod to the tall skyscrapers in Bel Geddes’s future cities?). Its façade is clean and sparsely adorned (a design aesthetic made popular by Bel Geddes later in his career). And on its roof is a clothesline (as everything Bel Geddes designed was simultaneously fanciful and functional—see his designs of radios and restaurants). I’m tempted to believe, like Bachelard, that “when we examine images of immenseness, tiny and immense are compatible . . . If a poet looks through a microscope or a telescope, he always sees the same thing.” I see greatness in a doll house, domesticity in massive urban plans.

See the mini/immense doll house plans and accouterments yourself in the Harry Ransom Center’s archives now, or wait until September to see them in the Ransom Center’s Bel Geddes exhibition.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago