Image credit: The Blanton Musuem of Art

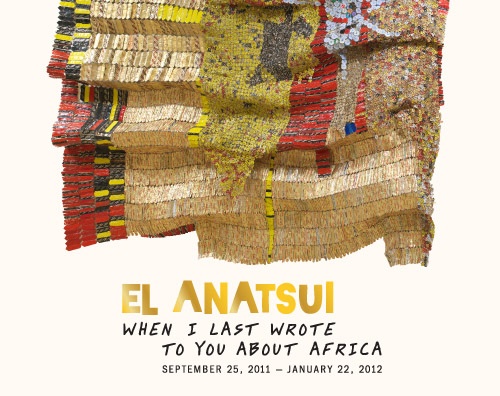

El Anatsui’s art is haunting. The shimmering bottle tops of his most recent pieces, meticulously netted and woven with the help of his young crew, speak of previous uses, prior intents, and pasts that pummel and prod. A retrospective exhibition of the Ghanaian artist’s 30-year career is currently on view at UT’s own Blanton Museum of Art. The exhibition, “El Anatsui: When I Last Wrote to You about Africa,” is a wonderful investigation of the tangible ways that the past weaves itself into our present.

A few weekends ago, I roamed through the exhibition, utterly amazed and dazzled by Anatsui’s use of reclaimed and repurposed materials to make art that spoke of the history of the artist, his materials, and West Africa. One of the many standout pieces from the exhibition was Akua’s Surviving Children from 1996, which was constructed during Anatsui’s residency in Denmark.

Image credit: The October Gallery

Although Anatsui was invited to Denmark to commemorate the 200-year anniversary of Denmark’s abolition of the transatlantic slave trade, his Akua does more than just jubilantly praise the end of centuries of horror. His materials hint at a history of violence and oppression, as he uses driftwood from a Danish shore and nails from a foundry that used to manufacture the very guns that were used by Danes to round up slaves on the Gold Coast. The driftwood, slowly worn down by the waves, is reimagined as a group of marching people with fire-blackened faces; the nails, made at the very site that used to manufacture weapons that caused the subjugation of millions of Africans, have been reimagined as the glue that holds together the marchers. A shared past of subjugation and violence haunts the marchers who stand, defiant against all odds.

Instead of driftwood and nails, another standout piece from the exhibition, 2008’s Oasis, uses Anatsui’s signature technique of woven bottle tops from liquor bottles. The juxtaposition of the aesthetic value of a piece like Oasis (which really does feel like a drink of cool water) with the moral message (just how many liquor bottles were consumed for Anatsui to make his art?)—is staggering. As tangible representations of a community’s consumption, the liquor bottle tops—with names like “Liquor Headmaster”—are woven into a traditional art form from West Africa, cloth. The past is revisited (and possibly mourned?) through traditional weaving techniques using unconventional materials.

Image Credit: Jane Katcher / Peter Harholdt

But, as discussed in a recent talk between El Anatsui, curator Lisa Binder, and art historian Moyosore Okediji, Anatsui’s work isn’t just about mourning the past—it’s also about chance and movement. Anatsui’s bottle top weavings aren’t just social and political statements. They’re beautiful and freeform, too. The display of Anatsui’s art is left to the whims of museum curators, who choose to show us glimpses of the backs of the pieces, which often are as beautiful as the fronts. Anatsui’s work makes us gaze just a little longer; it makes us take a second look. His pieces are remade with our every glance. There is hope that the past, too, can be remade and reshaped just as the curators shape Anatsui’s art, which itself reclaims, by chance, materials that others had left for dead.

Don’t miss your chance to see “El Anatsui: When I Last Wrote to You about Africa” in Austin. The exhibition is at the Blanton Museum of Art until 22 January 2012.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago