Danie Mellor is an Australian fine artist whose themes integrate environmental and socio-historical concerns. His message isn't quite as "left-brained" as the ideal I'm seeking (my goal is to find art whose ideas are clear through the art itself, without a separate artist's or museum statement). But there's something to be learned from Mellor about ways to achieve that ideal. Plus, his work is so beautiful that I'm utterly seduced into presenting it here.

Mellor uses a vocabulary of indigenous Australian animals and people paired with classic English china patterns. For Mellor, the kangaroo represents (as explained by a wonderful National Gallery of Australia audio guide), "all the native animals and indigenous people who lived in this land before white settlement." As for the blue china patterns, "The English firm Spode manufactured blue and white china in the late 18th century around the time of white settlement of Australia. The famous willow pattern, adapted from Chinese ceramics, became popular at this time. It demonstrates another way in which English culture absorbed another, creating a fabricated history." Artlink Magazine described another of Mellor's works as signifying "how colonisers always get things wrong; how Europeans looking for China and its fine porcelain manufactures, stumbled instead upon the land of the kangaroo, and traded and planted ideas of racial and cultural superiority."

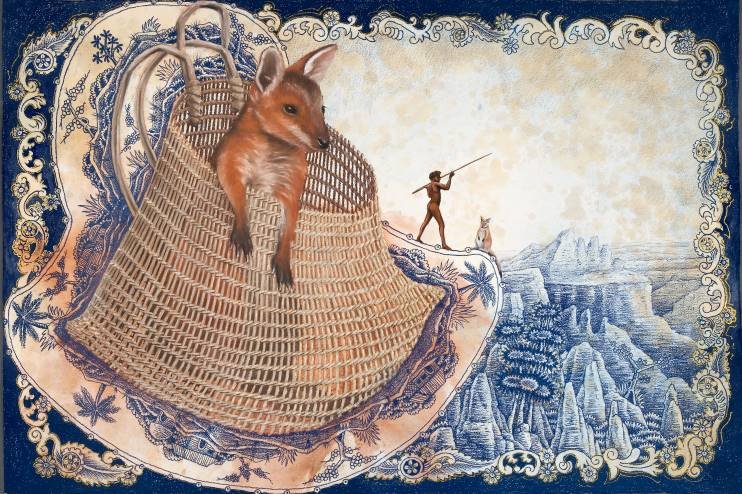

Dreaming Beyond Paradise (Let Sleeping Giants Lie) by Danie Mellor

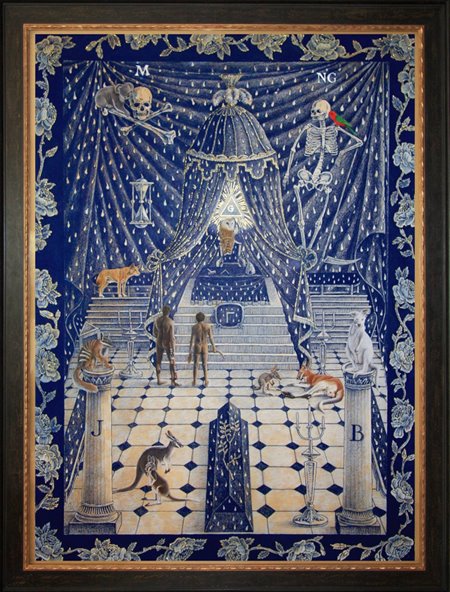

Once we know the language of Mellor's vocabulary, we can feast on his images and feel some of the tragedy of imperialism's domination of native habitat and culture. This dual vocabulary of English china and indigenous animals underlies even a more complex work like "New World Order (The Visitors)," in which Mellor also uses Masonic and other imagery:

In the lessons-to-be-learned-for-artists department, the very different visual qualities of Mellor's two primary components make his work very readable. The china pattern is elegant and finely detailed. The indigenous Australian elements are live creatures painted a bit more roughly.

Color above all distinguishes the Australian from the British in Mellor's art. The imperialist element is blue and white. The indigenous Australian is warm browns and oranges. The two are on opposite sides of the color wheel, reinforcing the contrast between the two.

So fellow artists looking to communicate left-brained ideas through right-brained art might draw on Mellor's device of creating a limited, easily-graspable vocabulary whose elements have high visual contrast. The viewer will then be able to easily distinguish the components of the vocabulary.

Another lesson learned through Mellor's work is how he speaks of tragic events with tenderness, joy, and fun. This is important in fine art when it takes on difficult issues. We're only human, after all, and we need to have some reward for facing catastrophe and reasoning ways to repair it.

Mellor also illustrates the fact that sometimes the best tool to express harsh reality is actually surrealism - through the artist inventing a whimsical version of reality rather than actual reality. Mellor places a kangaroo fast asleep on the bridge of the Spode willow china pattern. He paints an indigenous Australian man raising his spear over vertiginous painted-porcelain mountains.

What makes Mellor's surrealism speak so eloquently about reality is that the elements he chooses are visual synedoches: china patterns represent British imperialism; native animals represent the indigenous Australian people, culture, and natural world. The artwork we looked at in my last post, Nina Paley's animated film "THE STORK," is based on a visual metaphor - two elements with something in common. Mellor's work is based on the contrast of two very different synecdoches. They are two great examples of visual rhetoric.

PS Since we've been talking about science in art elsewhere on viz., you might want to look at Mellor's installation at the National Gallery of Australia and listen to the brief audio description. The installation's very long title is "The contrivance of a vintage Wonderland (A magnificent flight of curious fancy for science buffs, a china ark of seductive whimsy, a divinely ordered special attraction, upheld in multifariousness)." It's a joyful/tragic riff on "artificial and didactic" old exhibits in socio-historical and natural history museums. It's accompanied by a poem by A. G. Bolam, "The Trans-Australian Wonderland:"

A wonderland of truly wondrous things

That nowhere else upon this Earth are found;

Of reptiles rare, and birds that have no wings,

And animals that live deep in the ground;

And those poor simple children of the Earth,

(A disappearing race you here may meet),

Whom whites have driven from their land of birth

To regions still untrod by booted feet.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago