Image Credit: Hudson Valley Almanac

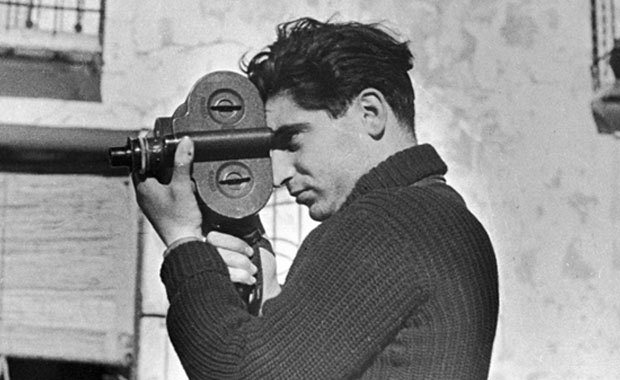

"If your pictures aren't good enough, you're not close enough."--Robert Capa, founding member of Magnum. d. 1954, landmine accident

Currently on exhibition at the Harry Ransom Center is a carefully curated selection of Magnum photos, drawing from the organization’s archive housed at the Center. Magnum, an elite professional photographic cooperative, brings together some of the world’s premiere photographers in a collaboration resistant to the commercial demands of photojournalism. This week on viz., we’ll feature the exhibit and explore issues central to visual argumentation and mass media. This post will explore what possibilities arise when photographers become their own producers and distributors—what influence do the conditions of production have on the genre of photojournalism itself?

AUDIENCE Many photojournalists speak of the “poster effect”—a bold, central image and a clean, contrasting background. The “poster effect” assumes a disinterested, distracted audience who must be coaxed into viewing the image amidst a complex matrix of visual competition. Below is an example of the "poster" effect. This image, taken by DC freelance photographer Mannie Garcia, was used by Shepard Fairey (without permission) in the iconic Obama HOPE poster.

Image Credit: The Online Photographer

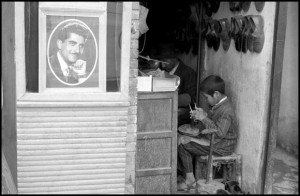

The Magnum photos arguably make different assumptions about a general audience—at the heart of the organization's ethos is the belief that people are interested in the depiction of human experiences and events. Reading this audience in good faith, a condition which is possible only when we remove photography from its commercialized context, opens up artistic possibilities. Below, Inge Morath plays with the convention of "poster" photography by including a posed photograph alongside a boy cobbling shoes in Iran.

Image Credit: Perceptive Travel

I was struck by how seldom Magnum photographs relied on the conventions of high art to communicate their message. Instead, I observed tactics that subtly drew attention to photography as a medium rather than as an unmediated experience. These compositional techniques showed respect for a mass audience and assumed they wanted more than a photograph that exactly replicated experience. Rather, these photographs meditate on what it means to capture an experience at all.

From Henri Cartier-Bresson's series The Great Leap Foward. Image Credit: Personal Photograph.

From Henri Cartier-Bresson's series The Great Leap Foward. Image Credit: Personal Photograph.

COMPOSITION These photographs often resist the “poster effect” and instead include jarring edges, multiple centers of movement, and background that resists its position vis a vis the foreground. Below, Burt Glen plays with photographic convention to depict integration in Little Rock, Arkansas.

Image Credit: Personal Photograph

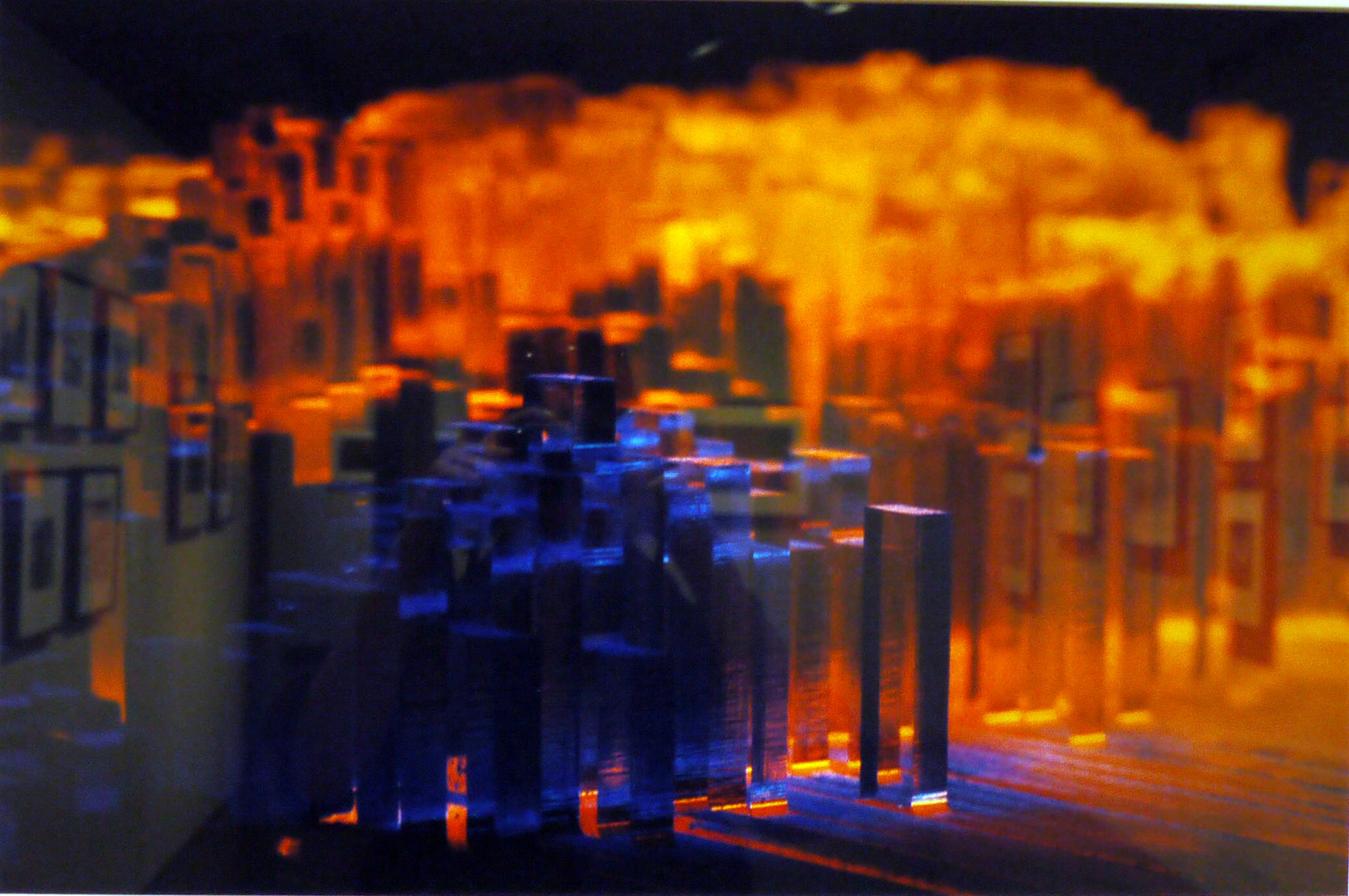

TECHNIQUE Rather than creating “true-to-life” images, the Magnum photographs are often interested in using the camera lens to see beyond the naked eye. In so doing, they often highlight the limits of both the camera and of visual memory. Below, Erich Hartmann photographs data output of an IBM voice recognition study in an attempt to visualize sound.

Image Credit: Personal Photograph

MEDIATION Unconventional cropping, composition, and photographic technique bring attention to the photograph as a medium, rather than a transparent window into experience. They challenge the idea that photography represents memory and suggest that our cognition, rather, has shifted with the advent of photography. While commercial photojournalism often capitalizes on the relationship between human memory and photography, presenting photography as an artifact of memory an therefore memory available for consumption, the Magnum photos challenge the assumptions underpinning “photorealism” (that is, that a painting of a photograph is as close to the real scene as a painting of the scene itself). By daring to bring attention to the medium of photography itself, the Magnum photos seem to suggest that the photographic has altered our perception of memory, rather than the other way around.

Below, Paul Fusco depicts Robert Kennedy's funeral train by using an unconventional f-stop setting to depict the movement of the train.

Image Credit: Agnostica

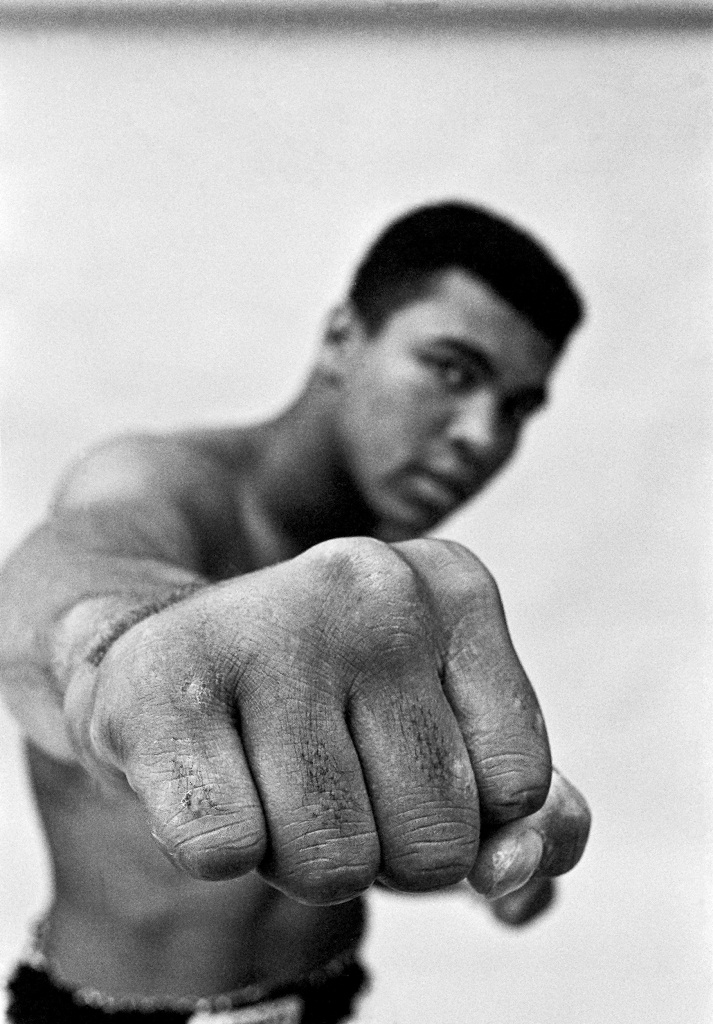

THE PERSISTANCE OF THE COMMERCIAL Despite all the ways in which the Magnum photos resist the conventions and assumptions of commercial photojournalism, the commercial persists. Magnum's experiments in the digital acknowledge competitition from new media as a driving inspirational force. And human experience itself cannot, of course, avoid the commercial as a formative part of cultural experience. Magnum photos often play with commercial conventions in order to make subtle statements through the photographic medium itself. For instance, Muhammad Ali's fist here is the real celebrity. Its owner is merely relegated to the background.

Image Credit: Roberta Cucchario

We hope you will enjoy the rest of the week's post on the Ransom Center's exhibition and offer us your own thoughts about the intersections between photography, visual rhetoric, and the digital age.

The opinions expressed herein are solely those of viz. blog, and are not the product of the Harry Ransom Center.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago