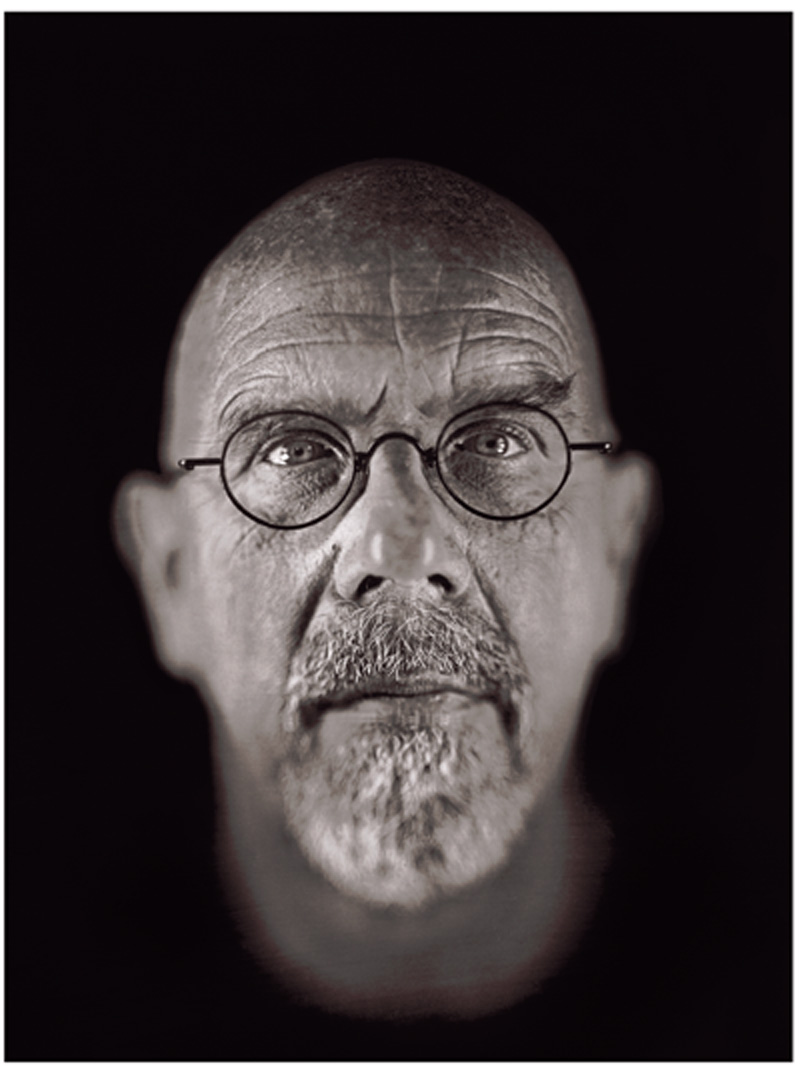

Image Credit: Chuck Close

Via Austin Museum of Art

I recently went to the Chuck Close exhibit at the Austin Museum of Art, which gave me a lot to think about. Close is known for the scale of his portraits (think: 9-by-7 foot

painting of a face). He is also known for paintings that make you

think you are seeing a photo. As Donald and Christine McQuade explain

in Seeing and Writing 3, his style is "photorealism or super-realism, which attempts to

recreate in paint the aesthetic and representational experience of

photography." In the recent exhibit

at the Austin Museum of Art, Close's scale is not quite so collosal; there are several 8-by-6 foot tapestries, but most of the images are more like 2-by-1 feet (the digital pigment print pictured above), or

even 15 very small images, which are 11-by-9 inches. There are no paintings.

The

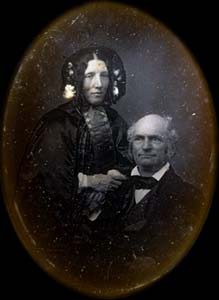

changes to scale and medium have to do with Chuck Close's recent work as a daguerreotypist. I

discovered this nifty, official term for 'one who creates

daguerreotypes' on the Harvard University Library's Daguerreotypes online exhibition, which has a gallery of holdings of this early form of photography, such as Harriet Beecher Stowe with her husband and a lovely image of the moon from 1852.

If I have totally lost you, the Oxford Dictionary of Art Terms

explains that a daguerreotype is "the earliest

viable photographic process, in which the image is produced by the

action of light on a silvered copper plate sensitized by iodine and

bromine. After exposure the image is brought out by the action of

mercury vapor...Each image is unique, there is no reproductive printing

from a negative, and the size is limited by that of the copper plate."

Image Credit: George K. Warren

Via Daguerreotypes at Harvard

Image Credit: John Adams Wipple

Via Daguerreotypes at Harvard

But

Close defied the prevailing belief that deguerreotypes could not be

reproduced. As the gallery guide explains, Close collaborated with

Jerry Spagnoli to reproduce the 15 original daguerreotype images into

digital pigment prints, jacquard tapestries, and photogravures, also

part of the installation. There is a lot (alot-alot) going on

here. Not only is Close self-consciously commenting on his ouevre of

paintings-as-photographs by directly creating photos (albeit by an

earlier process), the transformation of the original image into

tri-fold media richly implies how technologies alter the process of

(re)production.

Add to that, the 15 images are Close's

friends, and the poet Bob Holman, also friends with the crew, created a

portrait in words of each subject paired with the images. Whew. My

mind is working extra hard to try to fit it all in.

The

meta-cognitive, medium-bending work by Close could, I think, be a good

lesson for college-age students about cultural production. The material

means used to create any artifact (text or image) are significant,

including the tools, the canvas, competition with other mediums, the

interpersonal connections (Close collaborates on almost all of his

images), the physical space where the artist is working: the whole environment. Fluency in visual

literacy, I would argue, means students understand the source and

process of production, moreso than being able to close read an image in

isolation. The fact that the medium alters the size of the Close's portraits--and therefore the affective experience of the works in the museum-- might be a tangible way to convince students that the lesson is an important one.

The Chuck Close exhibit at the Austin Museum of Art is showing until November 8, 2009.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago