This semester, while teaching a course called "Photographic Narratives" for the Plan II Honors Program at UT Austin, I organized a panel of four top local photographers. One of the panelists, Sarah Wilson, brought work from her BLIND PROM series, which precipitated a discussion of ethics and the history of photography.

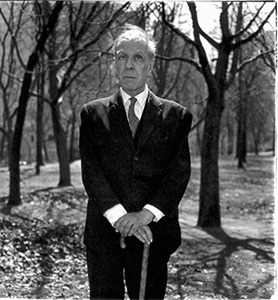

Image Credit: Paul Strand

This 1916 image by Paul Strand is one of the earliest notable

photos of a blind subject.

In an effort to create candid street photos, Strand had been

using a trick camera with a false lens that misdirected attention (like a

magician waving his wand—look over there!), allowing the photographer to get

close to his subjects without their knowledge. That subterfuge was unnecessary

in this case. The blind woman is the perfect subject for a photographer like

Strand—“the objective corollary of the photographer’s longed-for invisibility”

as described by critic Geoff Dyer in The

Ongoing Moment.

Portraitist Richard Avedon had different motivations for

photographing a blind subject. As he explained in the introduction to his 2002

book Richard Avedon Portraits, “I

photograph what I’m most afraid of, and Borges was blind.”

Blindness represents an obvious existential terror for

photographers, for whom eyesight is requisite for personal expression as well as livelihood. Which is probably why the blind are so often represented in

photographs as miserable or isolated. How else would you portray a subject who

is living your own nightmare?

Image Credit: Diane Arbus

Diane Arbus photographed blind subjects (including Borges)

among the transvestites, dwarfs, twins and bodybuilders that populate her

portfolios. In observing Arbus’s photos of the blind, we are more consciously

aware of the same voyeuristic exhilaration and guilt we perceive when viewing

photographs of any peculiar human subjects: we can see them, study them,

scrutinize them, pity them, envy them—but those eyes are just dark grains on

white paper. Those eyes can’t see us. They’re not even eyes.

In her series BLIND PROM, Sarah Wilson

introduces a new dynamic to the exercise of photographing the blind. In

documenting prom night at the Texas School for the Blind and Visually Impaired,

Wilson has assumed a ceremonial role in the most sacred of adolescent rituals.

The photographer is as essential to the complete experience as the DJ or the chaperone.

Photo © Sarah Wilson

As demanded by tradition, the young men and women of TSBVI

wear tuxedoes, corsages, evening gowns and neckties. Sighted sorority sisters

from the University of Texas volunteer their expertise with hair and makeup. The

blind girls cough in clouds of hairspray and hold out their fingers so their

nails can be polished.

And if you find yourself wondering why blind teenagers should engage in the same image-conscious

primping over which sighted students (controversially) obsess, Sarah Wilson’s

photos may invite you to wonder instead, why

shouldn’t they? The blind shouldn’t be excluded from the profound and

superficial experience of presenting

oneself to be seen by others.

"[The

blind students] understand that when a professional photographer comes and

takes their picture, it's important," Wilson said. Dressing up and

posing for the camera is not about seeing oneself, it’s about revealing

oneself—either as an act of vanity or as an act of self-expression.

Sarah Wilson’s BLIND

PROM is featured this month at the PhotoNOLA exhibition in New Orleans.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago