Lucas Cranach's Melancholia Image Credit: Art Tattler

Last week, I examined how painters of the nineteenth century revised the image of Phillipe Pinel, the famous mental health physician, to contribute to an evolving national mythology and edify the physician's archetypal (as well as vocational) role in fostering mental health. While the representation (as well as the specific job description) of the mental health practitioner has changed drastically over the past five centuries, one cannot help but notice that there are striking continuities to be found in representations of people said to be afflicted with maladies of the mind. Today, we will take a look at some remarkable consistencies to be found linking 16th and 21st century visual representations of one of Western society's most frequently visualized maladies: melancholia.

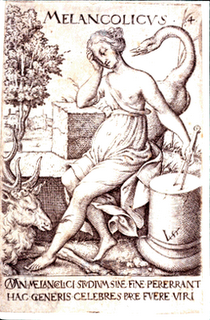

Virgilius Solis the Elder's Melancholia .4VS Image Credit: NIH - Images From the History of Medicine

Though a predecessor in some ways to depressive disorders and depression, the concept of melancholia carries with it a number of spiritual and behavioral connotations that cannot be mapped onto contemporary (American) diagnostic categories without losing a number of significant and complex meanings; the complete edition of Robert Burton's The Anatomy of Melancholy (1621), for example, devotes 1400 pages to the topic. Thankfully, a multitude of paintings and woodcuttings can help us demonstrate dimensions of melancholia that depart from contemporary mores of classifying and understanding such diseases.

Though melancholia proper was frequently associated with men as well as women, a significant contingent of artists chose to visualize the malady in the representation of dejected women. One can notice a number of significant similarities in the works of Lucas Cranach (1472-1553), pictured at the top of this post, and Virgilius Solis the Elder's Melancolicus .4 VS (1514-1562), directly above this image.

Cranach's painting depicts the melancholy figure as an angelic figure who is sitting in the corner of a room, looking blankly ahead. Since antiquity, Melancholia was understood in humoreal terms as an overproduction of black bile--in fact,the word "melancholia" simply means "black bile" in ancient Greek. And we can see this blackness in the top-right corner of the image. In the darkness we can barely make out the images of what appear to be witches on broomsticks--perhaps haunting the mind of this angelic figure whose countenance and posture seems to be in stark contrast to the disposition of the swinging cherubs. One almost gets a sense of a kind of swirling of the mind contrasted with the body's immobility. Likewise, we see a little dog sleeping at her feet. Solis's image includes some distinct similarites: the woman in this image sits with her face buried into her hands amidst a grouping of animals. As a counterpart to the stick held by the subject of Cranach's painting, we see that Solis's toga-wearing figure seems to be holding a sort of measuring compass. Does anyone have an idea of the significance of these items?

These images, in turn reflect some of the elements found in Albrecht Durer's depiction of melancholia. Durer (1471-1528) was an instructor of Cranach's, and we can see some similarities in their stylistic choices. Once again, we see the reclining dog at the feet of an angelic woman, and a sphere image as well. To take a guess at an answer to the question I offered in my previous paragraph, I will venture to guess that the compas in Solis's image, like the spheres in Durer and Cranach's pieces, may have something to do with rational/scientific creation--perhaps to an extent that it has an effect on spiritual existence. We may also note that Durer's image is replete with images of bells and (what appear to be) time pieces. And in the background of this otherworldly image, we see light (or perhaps the rays of "melancholia" itself) radiating from the distance.

Which brings us to our final images from Lars Von Trier's film,

Melancholia (2011). As we see halfway through

this trailer for the film, we notice a nude Kirsten Dunst laying on rocks, taking in the glow of a rogue planet, aptly named "Melancholia," which is on a collision course with the earth. Given this contemporary setting, Von Trier's choice to depict depression as a personal and cosmic apocalypse seems to be a throwback to the way in which the malady has been depicted for the bulk of its history. An analysis of the film yields further comparisons, as Dunst's character rejects scientific explanations (or in this film, wishes) that attempt to mitigate the danger. However, somewhat subversively, we see that the main character relishes in her melancholy, and fully accepts the doom it brings. Viewers might also note that one of the first images in the film is a horse that sits on the ground just as we first see Dunst's character--a strange image that nonetheless fits perfectly with five centuries of melancholia's representation.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago