"Revolutionary" By Wadsworth Jarrell Via Howard University

What does 1960s black nationalist art say to us today? TVLand's recent documentary on the Chicago-based Afri-COBRA movement suggests a few major takeaways. One is that images created for a community--by a community--inspire revolution. But I'd like to draw out a second theme voiced by former Afri-COBRA members who argue in a variety of ways that change starts with mind, and not the body.

"Wall of Respect" 1967 Via University of Chicago

The mural Wall of Respect was the beginning of Afri-COBRA activitism. The collaboration was meant to promote African-American heroes and artists while avoiding the physical clash that characterized racial rioting in 1960s Chicago. This begins the film's organization of artistic form (mind) apart from public protest (body). Artists created the positive imagery to change minds and insisted they were transforming their own minds. "We were confrontational in the sense that we were confronting ourselves and our people. We weren't confronting anybody else," said Afri-COBRA artist Napolean Jones Henderson. "We were challenging ourselves to see ourselves as we are."

The film continues a visual divide between politics and aesthetics. Historical marches, speeches, and sit-ins from 1950s America (in grainy black-and-white) appear less vibrant, if only in a visual sense. Against footage from the civil rights movement, Afri-COBRA paintings glow with rich "cool aid" colors and celebratory imagery. Afri-COBRA was a continuation and not a critique of civil rights, but the sets of images do register distinctly: domestic American civic imagery versus Africanist imagery, 1950s versus 1960s, documentary film versus imaginative new iconographies, African-Americans struggling to be seen at all versus African-Americans proactively setting out how they will be seen, often with non-Western forms or motifs.

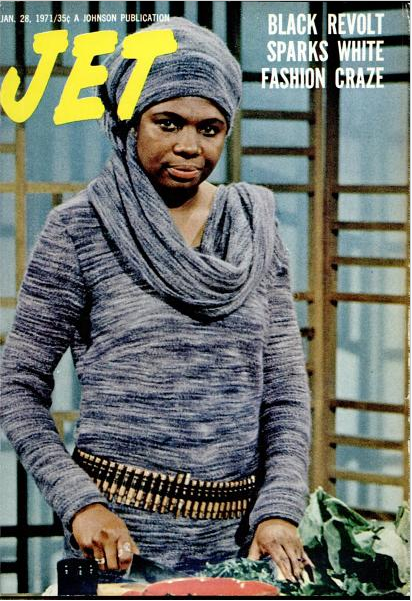

Screenshot of JET Cover Via Googlebooks

Afri-COBRA art often plays up its own rejection of literal revolution, such as the bullet motif. The 1971 JET cover features one of Jet Jarrell's fashion pieces, a bullet belt. (The mixed media painting "Revolutionary" incorporates real bullets.) In the Jet cover, the model wears the bullets and uses a butcher knife, menancing signals that she has the means defend herself physically. But that's only the first step in the representation here. The idealized 1960s domestic setting, the assured posture of the female figure and her knowing stare communicate that force won't be necessary. Change is inevitable, it says to JET readers, and is happening from within. You don't have to believe in the mind/body split to buy Afri-COBRA project, for the art movement was never truly disembodied. The rhetoric of mind, rather, was about Afri-COBRA members creating life on their terms, avoiding socially proscribed behaviors and ways-of-seeing.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago