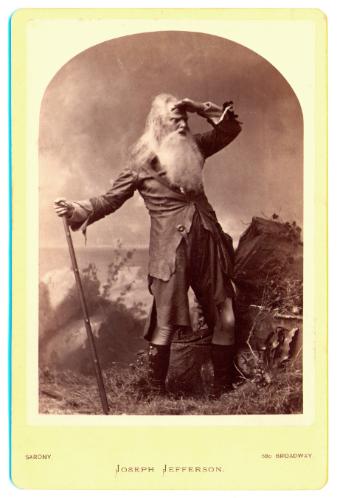

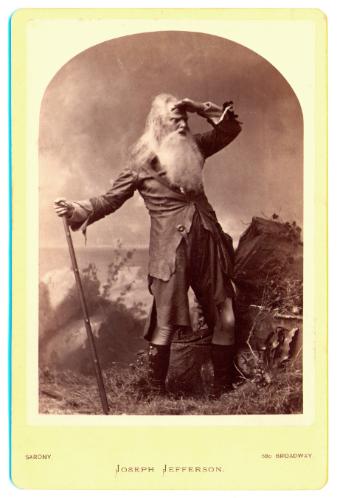

Image credit: Joseph Jefferson as Rip harryhoudinicircumstantialevidence.com

Just as there are as many interpretations of a text as there are readers, every new adaptation of a text weaves and builds a new story. Given technological constraints, the film version of "Rip Van Winkle" is necessarily short. As such, it’s important to consider the executive decisions made in paring out a new interpretation from the bones of Washington Irving’s 1819 tale. It’s also important to note that the film version was not an adaptation of Irving’s short story alone. The film was most likely created in part because of the popularity of the Jefferson stage play. The play was co-written by Joseph Jefferson and Dion Boucicault, the same Joseph Jefferson who starred in the film and worked with Laurie Dickson and American Mutoscope and Biograph Company to help to create the film.

In order to understand the shape of the film, it’s important to understand the more fleshed out version of the tale found in the play. The original play version[1] shows a number of changes to fit with melodramatic conventions of the day. In the play, the story is altered so that it is about betrayal, loss, and love. Interestingly, these themes are explored through a narrative that is mostly about property rights:

- In the play version, Rip used to own most of the town where the story is set, but the villain (a new character for the play), a money-lender and landlord Derrick, nefariously takes over during Rip’s sleep. When Rip awakes he finds that Derrick owns all except for Rip and his Wife Gretchen’s tiny cottage.

- But there’s hope: It comes to Derrick’s attention that despite his efforts to trick Rip by keeping him drunk all of the time, documents which Rip signed years ago were mortgages and not loans. Because the property has become so valuable with Derrick’s developments, were Rip to merely sell a fraction of that land he would pay of all of his loans and more.

- Scheming to trick the illiterate Rip, Derrick draws up a deed. The innkeeper’s son, who intends to marry Rip’s daughter is learning to read in school and translates the document to Rip, who, without a word avoids signing throughout the night’s drunken festivities.

- A storm descends and Rip comes home drunk. His wife and he fight and he leaves despondent. Meanwhile the children speculate that tonight is the night that Hedrick Hudson and the ghosts go bowling.

- Up in the mountains Rip meets Hedrick with whom he communicates via pantomime. He carries his barrel of drink to the other ghostly and also mute dwarfs where he delivers a monologue, partakes in the beverage and faints.

- When Rip returns he finds that Gretchen, succumbing to financial ruin, has married Derrick for support. Rip’s daughter Meenie, who wanted to marry the innkeeper’s son Hedrick, is told that he has been lost at sea and will marry Cockles, Derrick’s nephew, instead. (18)

- Hendrick reappears, having survived shipwreck. Though no one believes that Rip is who he says he is, he is able to produce a deed proving that the land is in fact his. Derrick and his nephew Cockles are chased off of their property, Rip and Gretchen are reunited, Meenie marries Hendrick and Rip toasts to everyone’s health.

When Dickson and the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company worked with Jefferson to make the film version, this is the play that they were working from. When we read the film, it might help to see it as informed by the popularity of the play, Irving’s story, and the novel medium of cinema. The first change viewers of the film will notice is that all of this very suspenseful drama is ditched. Perhaps because it is sentimental (the double love triangles! The swindle!) and film was cutting edge – a new medium which saw itself above the drawn out, outright clichés of the play. The drasticaly shortened story line was divided into eight scenes which are as follows:[2]

1) Rip’s Toast

2) Rip Meeting the Dwarf

3) Exit of Rip and the Dwarf

4) Rip meeting Hudson and Crew

5) Rip’s Toast to Hudson and Crew

6) Rip’s Twenty Years Sleep

7) Rip’s Awakening

8) Rip’s Passing Over the Mountain

As readers can see, what does remain from the original story is a preoccupation with altered states of consciousness, and an emphasis on the miracle of change over time. Because "Rip Van Winkle" is a story about change, and was in many ways forward thinking in its own time, the film might be, in some ways, a more faithful adaptation to the themes presented in Irving’s story than the melodramatic play.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago