Image Credit: Personal Screen Capture from Amazon Prime

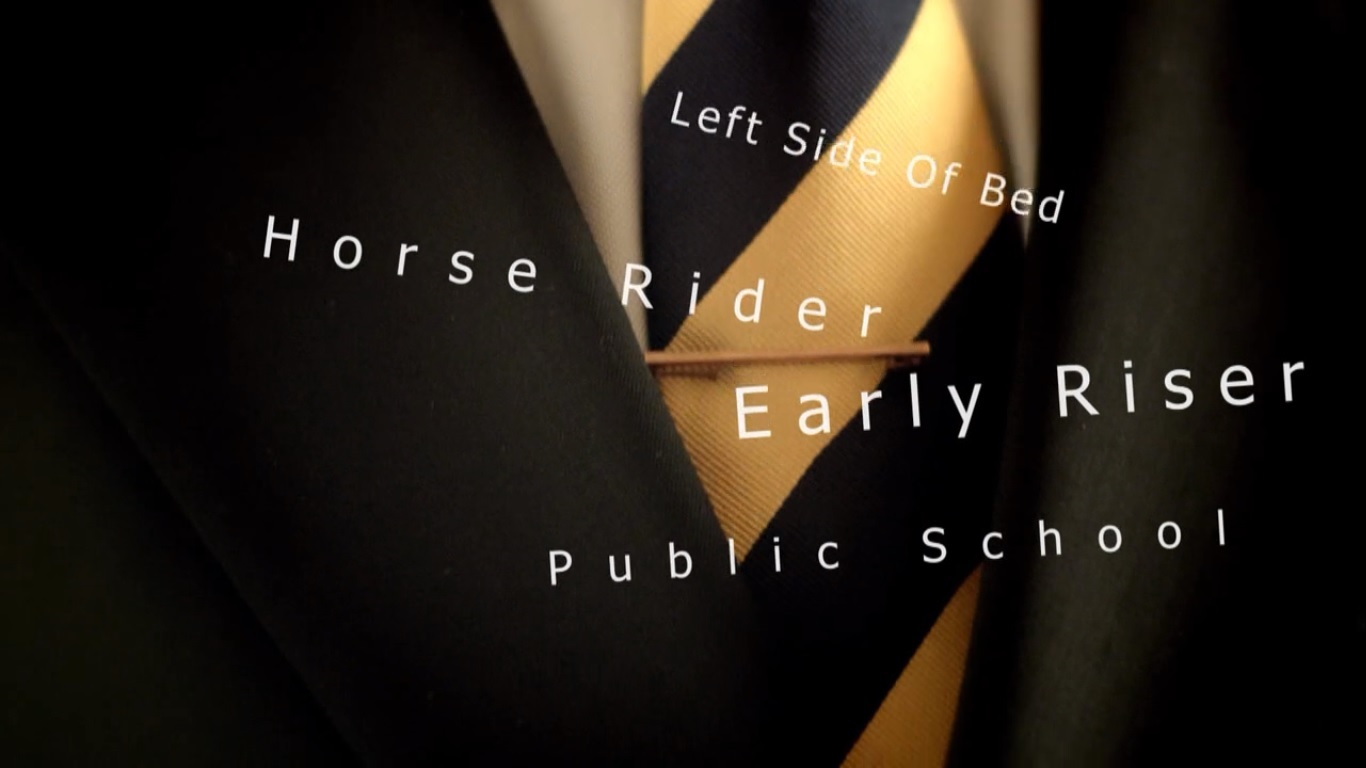

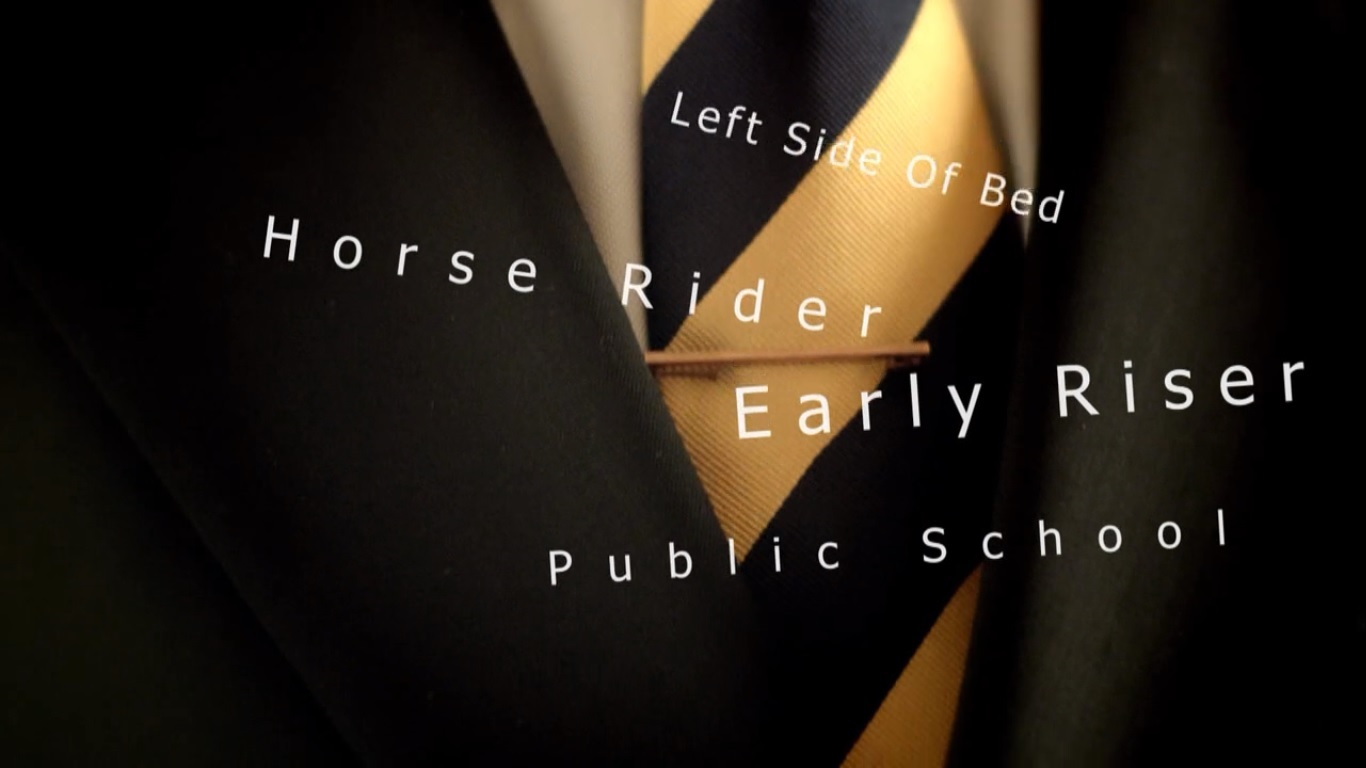

BBC's ongoing show Sherlock is a present-day adaptation of Arthur Conan Doyle's nineteenth-century detective stories, and it gleefully delights in its modernity by incorporating new technology and polishing up old visual tropes associated with the rationally-minded crime solver. Whether it's confronting viewers with just how resistant Sherlock himself is towards the popularity of his infamous deerstalker or transforming a first-person narrator's short stories into fodder for a personal blog , Sherlock 's self-referentiality invites its fans to think about the implications of these alterations. The alteration of the media used to tell the tales of the Great Detective Sherlock Holmes also introduces some arresting issues. If Sherlock's deductions were shrouded in mystery or only available to readers through Holmes's own explanations, the show actually allows viewers to “see” the detective's thought processes by stylistically superimpos i ng text onto the show's images.

Generally, the camera will helpfully zoom in on an item, suggesting the microscopic power of Holmes's vision, and neatly tag it with the conclusion Holmes draws from miniscule clues. In some cases, the viewer is able to n eatly follow the chain of logic. Wisps of short white hairs adorning a suit leads to the tag “Dog Owner,” for instance. In others, however, the magic is enhanced by a tagged conclusion that seems several steps removed from the image, or even fairly unrelated to the item in question. Holmes's penetrating observation yields information, data, facts that can then be presented in the manner of a conjuring trick to an awe-struck public.

In the Sherlock episode “Scandal in Belgravia,” Sherlock actually encounters a visual that yields absolutely no data. Not only is Holmes stumped, but the viewer is invited to experience his perplexity with several images accompanied, not by the coolly confident array of labels and conclusions, but with impotent strings of question marks. So what baffles the Great Sher l ock Holmes? A naked woman.

Image Credit: Personal Screen Capture from Amazon Prime

Holmes's failure to “deduce” anything about Adler suggests that a nude female body simply does not exist in the trac e able, reasonable world of causation. Unlike the attired bodies Holmes frequently analyzes for information, bodies that present information in terms of clothing choices, mud accumulated on particular brands of shoes, for instance, a naked female body is a complete and utter blank, a string of question marks. It is an indicator of nothing but its own immanence. Even before Holmes's confrontation with Adler, Sherlock has taken great pains to make the cunning blackmailer a veritable avatar or ideal for female sexuality. Her chosen profession, high-class dominatrix, couples with some cross-cut scenes before her meeting with Holmes to emphasize her sensuality. The scenes in question capture the “preparation” of both parties for their confrontation. Holmes attempts to pick a disguise that will help him infiltrate Adler's home (he ultimately settles on a clergyman). Adler sashays into a closet full of clothes wearing only a skimpy negligee. Holmes asks Watson to punch him in the face to contribute to his disguise. The camera zooms in on Adler putting on makeup (she chooses “blood” as her shade of lipstick). Finally, Adler tells her assistant that she will greet Holmes in her “battle dress.”

Image Credit: Personal Screen Capture from Amazon Prime

As Irene Adler boasts, it becomes quickly apparent to the viewer that her sensuality is indeed her weapon of choice. Throughout their confrontation, she seems gracefully in control of the situation, elegantly quipping to Holmes that any “disguise” is inevitably a “self-portrait” and jeeringly asking Dr. Watson, when he evinces discomfort with her nakedness, if he's “feeling exposed.” Adler's comfort with her own sensuality neatly contrasts Holmes's extreme discomfort with his. Adler's sexual power, clearly a comment on a woman's ability to manipulate masculine expectations and desire for her personal ends, certainly deserves its own conversation, and many writers on the internet have already tackled the sexism, or feminist empowerment, of Irene Adler as a character. Holmes's inability to glean any information from her nudity, though, seems particularly troubling and perhaps even inconsistent. First and foremost, the nude woman as a transparent marker of sexuality, is a popular conception that desperately needs to be challenged. For Holmes, there is simply no information to be obtained from Adler. She has made no clothing choices that would reveal personal quirks, individual experiences, taste, education, etc. She has “removed” all referents. Holmes does, however, take away her “measurements,” a combination of numbers that turn out to be the code to Adler's safe. Her physical fitness, her makeup, her hair style, apparently reveal nothing. I'm certainly not arguing that Sherlock should endorse the idea that an individual's “visual” bodily identity is somehow a completely reliable marker for “deeper,” perhaps essential, truths, but the idea that the female body communicate s only its own immanence is a notion that's disturbing in its own right. Along these lines, Holmes's insistence that she is “THE Woman” looks less like a compliment elevating her to eminence within her gender and more like an admission that Adler's inaccessibility makes her a perfect ideal of what woman really means: mystery, sex, embodiment, and, implicitly, anti-rationalism.

Despite Adler's cleverness, sexual potency, and air of mystery, Holmes does ultimately win the day. This point, incidentally, is a stark departure from Doyle's original story, “Scandal in Bohemia.” In the original, Adler absconds with the photographs, essentially besting the Great Detective, evinces no sentiment for Holmes, and requires no ultimate rescue. Admittedly, the show does play out this plot. It ends about thirty-five minutes into the episode, and the remainder is a creative extension of Adler's story. In Sherlock 's version of the tale, Holmes figures out the 4-letter password that unlocks Adler's “ SHER”-locked camera phone thanks to information he has gleaned from her body. Instead of the solid obstacle to rational discourse her body once was , Adler's dil a ted pupils and elevated pulse during an intimate moment with Holmes yields a piece of crucial information : love. Perhaps unintentionally, the show enacts a lesson in “reading” a woman's body, a lesson that ultimately gives Holmes the ability to outsmart Adler, to use her sensuality against her.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago