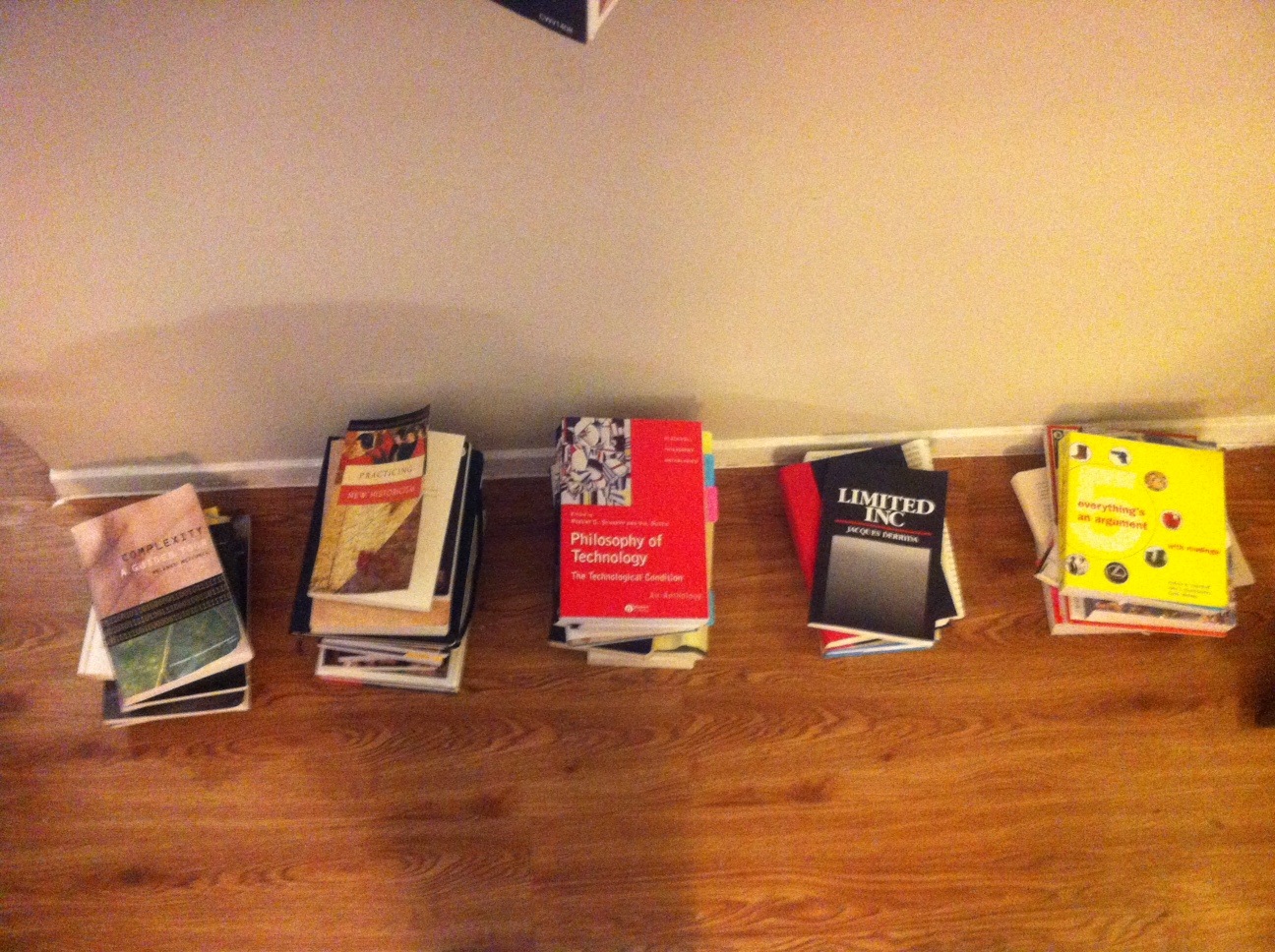

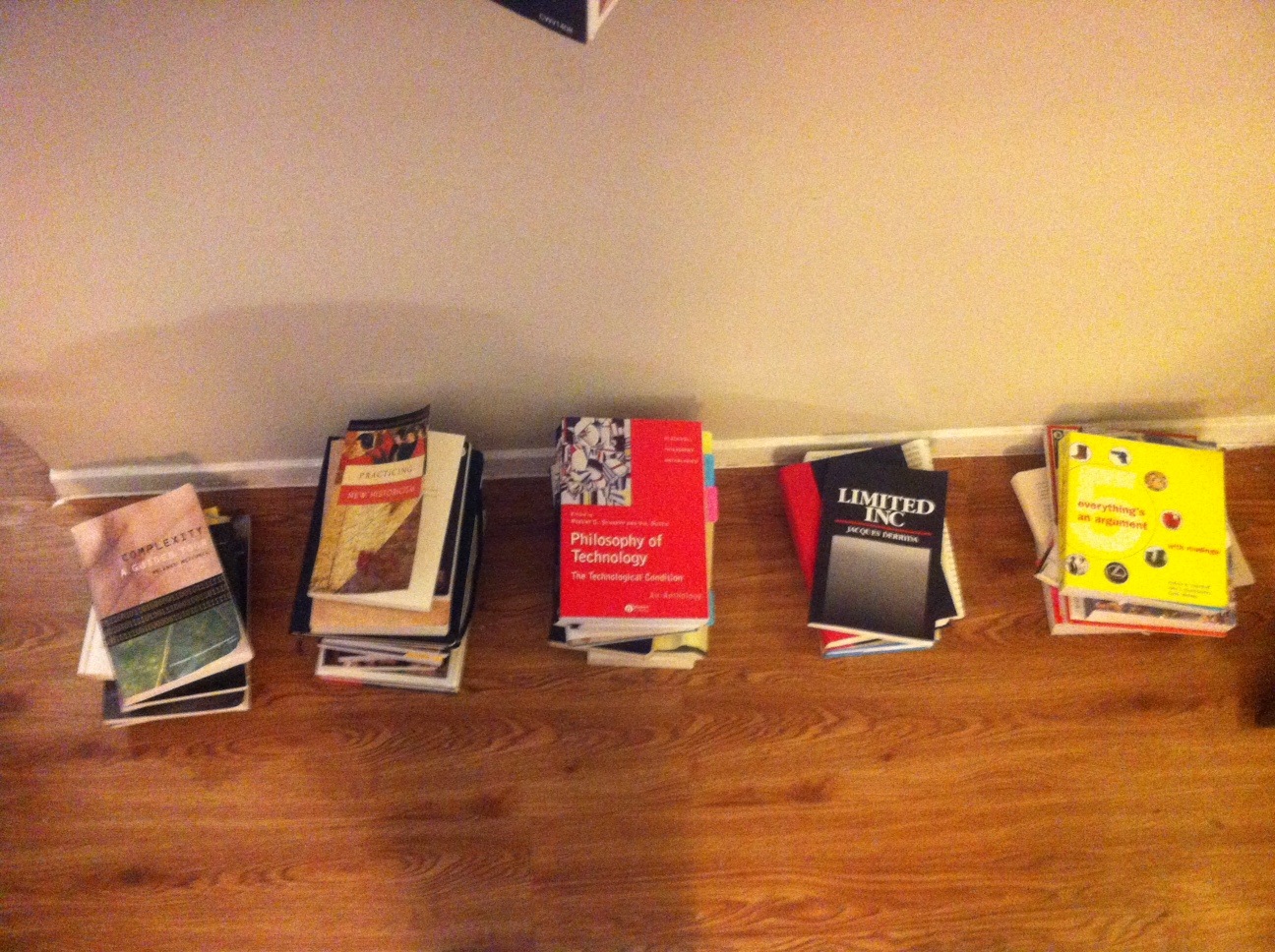

Above: An example of books serving in Ancillary Capacity #422: "The To-Do List"

In his book, “The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable,” Nassim Nicholas Taleb unapologetically and only somewhat jokingly points out some of the “superficial” benefits of the printed book versus the e-reader:

[I have realized] the foolishness of thinking that books are there to be read and could be replaced by electronic files. Think of the spate of functional redundancies provided by books. You cannot impress your neighbors with electronic files. You cannot prop up your ego with electronic files…Objects seem to have invisible but significant auxiliary functions that we are not aware of consciously, but that allow them to thrive- and on occasion, as with decorator books, the auxiliary function becomes the principal one. (Taleb at 319)

While the ability to impress your friends with your lofty collection might not be seen as a terribly compelling argument in the print/e-book debate, implicit in what he says is an acknowledgment of a separate, secondary (or tertiary, and so on) “meaning” that books can have that is entirely detached from the words written therein. Books, precisely because they are physical, tangible objects, lend themselves to a connection with the reader on multiple levels.

One of my law school textbooks- a behemoth entitled “Complex Litigation”- has spent much more time as the thing that saves my eyes and next by raising my laptop several inches off of my desk than it has spent as a research resource or as a source for pleasure reading. For that reason (among others), there is no way- even on a purely logistical level- that the electronic edition of “Complex Litigation” could ever serve the functions or exude the meaning that my individual copy has.

Even an identical print copy would fail to have as much meaning for me as my copy. A different copy wouldn’t function as a chronicle of my third year of law school. My copy is nothing short of a personal diary. The only difference being that, instead of strings of words, sentences and paragraphs, my reflections took forms such as highlights of things that struck me as important at the time, doodling and marginalia about nonsense that had nothing to do with law but which still bore significance to me, and scuffs on the cover that could only have come from carrying that goddamn thing around with me everywhere I went for about four months.

So, when I use an illustration such as my Complex Litigation textbook in support of my position that the e-book is not, and can never be, a substitute from the print book, am I missing the point? Many proponents of e-readers and the overall digitization of literature dismiss those clinging to the printed text of yesteryear as luddites who are over-romanticizing the past. Arguments pointing to the aesthetics and physicality of the print book are not merely dismissed. Rather, mentioning them actually serves to undermine one’s pro-paper stance in the eyes of those on the other side of the fence. At some point in the discourse, allowing “subjectivity” into your argument became tantamount to conceding its inferiority. (In his book, "The Case for Books: Past, Present, and Future," intellectual rock star Robert Darnton acknowledges this same basic notion in a manner far more articulate than I just did. Check out page 39, for example.)

I suppose this shouldn’t be terribly surprising in light of the fact that the Western world at large has become so obsessed with placing the “objective” and empirical above the subjective, sense-based experience that the propriety of that hierarchy isn’t even questioned. But it heats my balls, nonetheless. I mean, I could prattle on for days about the ways in which these supposedly “objective” observations are anything but objective. But I won’t. Why? Because I think it’s absurd to draw these hard-and-fast distinctions between the subjective and objective; I think it’s even more absurd to take the position that one of these two designations have some sort of intrinsic superiority over the other.

It would, of course, be hypocritical of me to fault those readers among us who truly do not find any value beyond the actual words comprising a book. If the e-reader is what floats your boat, good for you! There are many smart people making very compelling arguments consistent with your own, and I am not trying to devalue any of them. All I’m suggesting is that individuals who still argue that there’s a continued worth to the printed texts shouldn’t be dismissed as improperly irrational until you’ve had a chance to see their kick-ass makeshift nightstand.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago