Anticipating 2009 as the Year of Darwin,* Olivia Judson offered this suggestion last year: let’s get rid of Darwinism. She criticizes the Darwin-centric focus of both specialist and popular discourse as “grossly misleading. It suggests that Darwin was the beginning and the end, the alpha and omega, of evolutionary biology.” Judson’s complaint, of course, is nothing new: as a peeved St. John Mivart notes in Man and Apes (1873), “Again, the doctrine of evolution as applied to organic life…is widely spoken of by the term ‘Darwinism.’ Yet this doctrine is far older than Mr. Darwin…”

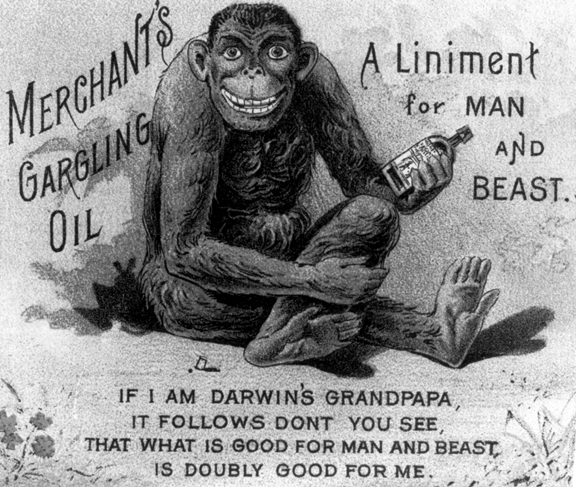

Image Credit: Cartooning Darwin

H/T: Seed Daily Zeitgeist

While preparing to teach this week, I came across a couple of intriguing resources that help to explain how the figure of Charles Darwin entered circulation as a scientific celebrity, an icon of sorts, beginning in the late 19th century. They suggest the active role of popular visual culture in the intertwining of Darwin with evolution, even as the meanings of that term remained multiple, fragmentary, diffuse.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago