Site informationRecent Blog Posts

Blog Roll

|

assignmentNew Journalism Publications: A Multimedia Mash-Up by Nathan Kreuter

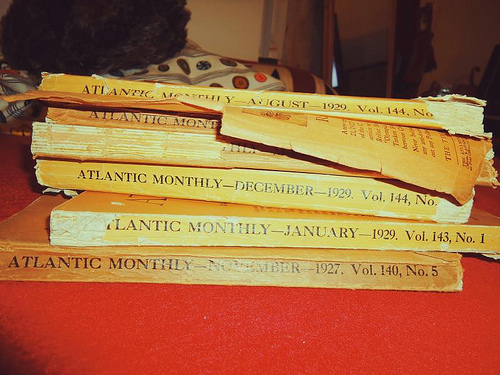

Image Credit: fidgetrainbowtree For a handout, download the PDF document outlining this assignment. For your second project you will be working in groups to create a 3-5 minute multimedia presentation. The content of the presentation should focus on one of the following publications: Rolling Stone, Esquire, Vanity Fair, Harper’s, The Atlantic, and New Yorker. Your task is to choose one of these publications and compare its print culture in two different decades. By “print culture” I mean everything printed in the magazine, from features and fiction to interviews and advertising. Your task is to argue in your multi-media presentation about what the publication in each of those two decades you choose tells us about American culture at that time, as well as to point out the changes between those two decades, and speculate as to what those changes might mean. All of the publications listed here are held in the PCL’s stacks. While UT does have some digital copies of more recent issues, you would be better served by going to the library and looking at the physical issues. And for older issues you won’t have a choice. So you’ll need to get into the library. The format of these projects is a multi-media presentation, which must be no less than three and no more than five minutes long. It also must be entirely selfcontained, which means that when you bring it to class you can simply press a play button and we can watch and hear the entire presentation. At the least interesting (and least likely to garner a high grade) end of the spectrum would be an automated PowerPoint presentation, and at the most interesting end of the spectrum would be some sort of video that incorporates images and words from the original publications, as well as music and some sort of narration to make your group’s observations and argument. In the coming days I will provide you with the rubric that I will use to grade the presentations. You also need to quickly decide which publication your group will cover. I would prefer that no two groups work on the same publication. As always, you should email if you have any questions. Important Dates: Wednesday, February 25th—Project Assigned Monday, March 2nd (Texas Independence Day)—Let me know which publication your group will cover, rubric provided to students Monday, April 13th—Final Projects Due in Class Creating a Common Class Publication: A Unit Plan by Nate Kreuter

Image Credit: nublue For a handout, download the PDF document outlining this assignment. For our second major writing assignment we will be producing a class publication. Everyone will contribute to the publication, albeit in some different ways (see below). I propose that we "write" a publication dealing, in the broadest sense, with "Austin." You all should choose subject to follow and write about that say something about what makes Austin different from other cities. The assignment is really that broad. And we will have a very boring publication if everyone writes an expose of a frat party. This will require you to get off campus and engage with our broader community. Keep in mind that the New Journalism often approached culture from the fringes—you might want to do the same, but whatever you do, stay safe. If you have a difficult time coming up with ideas, I'll happily help you brainstorm. Under no circumstance should you put yourself in a dangerous or even uncomfortable position to get your story. There are plenty of great stories available without having to take such risks. Also, your grade will be low indeed if you indulge in some form of reportage that is simply about, say, getting high with your friends. The New Journalism is hip and cool, but don't let that compel you to act or write in ways that you don't want to be recorded for posterity. This, despite the cool of the New Journalism, is still a formal assignment, and should be treated as such. We will talk about journalistic ethics and your responsibilities to yourselves, your subjects and your readers throughout this project, and I strongly suggest that you take notes when we have those conversations. In terms of composition, I want us to expand on the typical notion of writing. You could choose to write a traditional essay for this project, but I strongly encourage you to experiment with other forms of compositions: videos, radio essays (a la This American Life), multimedia presentations, flash presentations, and photo essays are all viable options for this project. If you would like to attempt a composition in a medium you have not worked in before, Nate will be happy to direct you to one of the many campus resources available, such as DMS, to help you with your project. Journalists—Journalists will write stories relevant to the topic of the publication. They will submit polished, well documented stories to the editors. Stories should be between 2000 and 5000 words. The editors may reduce the text as it appears in the final publication, or they may ask a journalist to add or flesh out parts of their story. Commentators—Once the journalists' stories have been selected the commentators will decide upon a strategy for making sense of what the stories mean. They will each "write" a critical essay commenting on one or more stories and the stories' significance. They will try to tell us what the reporting means. Editors—Three editors will be selected from applicants to review the stories submitted by the journalists. They will determine which stories to feature, as well as making constructive suggestions for how the stories might be improved before final publication. In consultation with the class as a whole, individual contributors and Nate, they will set deadlines for story submission and final publication. Editors will also "write" introductory and concluding material, as necessary. Designer—The designer will be responsible for the layout and final publication of our work. They will need to be familiar with web-based and traditional publishing techniques. They will be responsible for bringing all the various media together in one "location" and forming them into a coherent "publication." Grades—Everyone will get two grades for this assignment. Nate will grade the final publication, for which everyone will receive the same grade. This grade will count as 10% of students' final grades. Additionally, Nate will grade students' compositions and contributions to the final publication, grading the publication in their prior-to-editing state. This grade will count as 20% of students' final grades. Deadlines—by 10/10 you should email Nate with two things: your preferred position on the class publication (journalist, editor, commentator, designer) and your qualifications for that position. The "default" position will be journalist. Also, everyone, regardless of their preferred position, should email Nate a brief (no more than 300 words) description of what you *think* you would like to "write" about for the publication, assuming that you are a journalist. On 10/13 Nate will inform you of your position, at which point he will also discuss your story ideas with you individually. All additional deadlines for submissions and publication to be determined by the class as a whole. As always, email Nate if you have any questions about any component of this project. Flickr Visual Rhetoric Assignment by Eileen McGinnis

Image Credit: topgold For a handout, download the PDF document outlining this assignment. Overview: At the start of the semester, my students in “The Rhetoric of Science Writing” read an excerpt from Pale Blue Dot, Carl Sagan’s prose meditation on a grainy image of Earth taken from the Voyager One mission. Without the accompanying text, the photograph is pretty unimpressive. However, after reading Sagan’s words, it would be difficult for readers to question the value of that image, since at stake is nothing less than our definition of what it means to be a human occupant of Earth, an argument for our responsibilities toward each other and toward the planet. For their final short assignment, students themselves try on the role of “science writer”: they are asked to find a scientific image, contemporary or historical, and write a brief (500-600 word) argument that attempts to persuade a non-scientific audience of their image’s value. Their goal is to convince readers that their chosen image warrants a closer look and to leave them with a more informed appreciation of its contents. Rather than submitting the assignment and accompanying image to the instructor, they will post both the image and text to the photo-sharing site Flickr. Using Flickr to collect students’ work will then enable them to present and discuss their images on the following class day. In addition, the relative “publicness” of this assignment will hopefully foster a sense of community and shared purpose (students can use content-specific tags to make their visual arguments more easily searchable by a broader audience). Of course, this exercise doesn’t necessarily have to come attached to formal assessment. The broader idea here is to use Flickr to create a class “image gallery,” which will facilitate discussion about both individual images and trends across a group of images. Flickr would also work for a more informal homework assignment or even an in-class activity on visual rhetoric, in which students retrieve and analyze visual artifacts for class discussion. Pedagogical Goals:

Description: Rather than walking through the details of my particular assignment, I’ll provide a couple of logistical tips that are more broadly applicable to using Flickr in class:

Modifications: The “Groups” feature on Flickr might offer another way to organize your students’ posts versus having them tag the photos. If you were concerned about access, it would also allow you to control who gets to view the images and/or comment on them. Credit: Thanks to John Jones for helping me figure out the logistics. Google Maps Assignment by Sean McCarthy

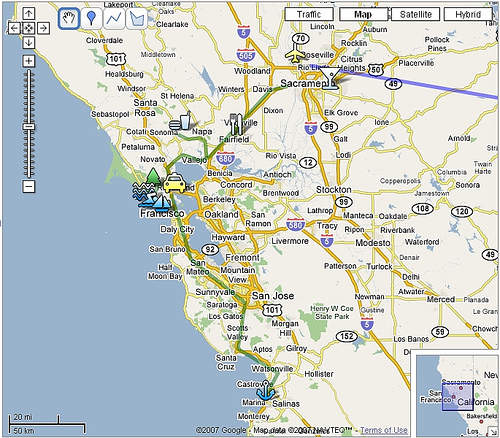

Image Credit: billolen For a handout, download the PDF document outlining this assignment. Objectives: In this assignment, students are asked to create a GoogleMap to map a topic. GoogleMaps allows students to create their own journeys and annotate place markers with text and multimedia content; they can upload their own photos to their map, link to YouTube clips, write text and link to blogs and other kinds of websites. This free service encourages them to build maps that tell stories in a visually interesting, geographically situated way, and all sorts of people, from news agencies to public transportation services, are now using maps to create new kinds of content (commonly called 'mashups'). GoogleMaps shows how fun and creative writing on the web can really be. With no experience and lots of imagination students can join the most creative people currently delivering content on the web. In this assignment students will literally "map" a topic of their own choosing that relates to globalization. In other words, they are going to use the multimedia environment of GoogleMaps to tell their story and present their research to the rest of the class (and the rest of the world, if they wish!). Materials/Equipment: Internet access and a Google Account. Preparation: Students need to be taught how to navigate GoogleMaps. Fortunately, GoogleMaps are really easy to use. These introductory videos will show you the basics. Here’s the page that gives you step-by-step instructions on how to build your map. This YouTube video shows you how to create interactive place markers. Finally, Google Maps Mania is a great blog that shows how people are using GoogleMaps around the world. It provides links to hundreds of maps and is a great place to start thinking about your own map. Procedure: Midterm maps due: week 10/28 Final Map Due: 12/4 Accompanying Paper: due 12/4 Assignment Specifics: The map will be evaluated as a Learning Record work sample. So, be sure to make observations about what you are learning as you are creating your map and use the work samples as a way of building your research. A draft of the map is due the week of 10/28, when we will spend the week on presentations of your maps. The final map is due the last day of class as a work sample in your LR. In addition, you need to produce a two-page, single-spaced explanation of your choices for the map. In this short paper you will explain the idea behind the map—the intended audience, the choice of sources, why you chose that particular layout. etc. My criteria for assessing your map are simple: how well do you use the map technology? How clear is the story you are trying to tell? How do you balance writing in the map with multimedia content? Will this map be useful and legible for your defined audience? Will they understand what this map is about without having been in this class? There are a number of ways you can fill in your map. It must have at least 8 placemarkers that contain text, and some sort of reference to other multimedia resources (photos, hyperlinks, YouTube clips etc). The writing must by your own, though you obviously can use links to other text, audio and visual material to help tell your story. Part of the skill you will develop will be to decide what information to write into the placemarker and what you will leave to your hyperlinked sources. For example, how well can you tell the story within your map without forcing your audience to jump to other websites to fill in the gaps? These are the kinds of important choices you must make. The success of your map will depend on the clarity of your writing, what sources you use and how you incorporate them, and the overall coherence of the project (in other words, can the reader easily understand the whole idea behind the map?). You will need to do some research, but that research could include your own photographs (or photos you find on the web); your own interview or podcast (or one you find on the web), a really cool YouTube clip, or an informative website or blog. Remember, your GoogleMap and midterm paper can be on the same topic, so research for the map can count as an opportunity to develop your research for your midterm paper. The only real rules are that the map must in some way relate to the ideas we are talking about in class. It must be informative (in other words, it shows research) and there must be writing to assess. DON’T present me with just a bunch of photos or hyperlinks; it’s how you write about them that counts. Presentations will be on the week of 10/28. The feedback you get from the class during these presentations you will be able to clarify your ideas and build a better map. After the presentations you will buddy with two other classmates. For the rest of the semester, you will be helping each other evaluate your maps using the map rating function built into GoogleMaps. Assignment: The Flexible Final Project

Submitted by Megan Eatman on Thu, 2011-04-28 13:26

Screenshot from student project Evolution, Not Revolution by Lacey Teer Last semester, I wrote my final blog post about using iMovie in the classroom. This semester, I attempted to correct some of the issues that arose when I asked all my students to use multimodal argumentation for their final papers. What follows is an outline of the final project I assigned and information about the changes I made to address various problems. This information will also appear on our "Teaching" page, along with sample student projects. Google Earth Pedagogies: A Survey of Pedagogical Applications

Submitted by Laura T. Smith on Mon, 2010-02-15 11:33

(Image Credit: Google LitTrips) As I’ve been previewing Google Earth educational applications on the web, I’ve noticed that while many disciplines (science, geography, history) are using Google Earth to engage students and invite them to create within the software, applications for the English classroom (at least those that are featured and discussed on the web) overwhelmingly take the form of teacher-made presentations. I imagine that this tendency speaks to an ongoing conservatism about the design of writing assignments, a desire to retain the five-page paper as the product of the literature and writing classroom.

Tags:

Assignments for Visualizing the Writing ProcessThe group of assignments below present a number of opportunities to train students to think visually about the writing process. Although they are not explicitly designed to teach visual rhetoric, or to inculcate the skills of rhetorical analysis with visual subjects, they are nonetheless implicitly designed to offer students fresh perspectives on the writing process. "Perspectives" is a key term, since these projects ask students to use visual processes to reorient themselves to their writing, by producing visual objects such as annotated outlines, mindmaps, and other brainstorming projects that are more than text-based. The skills sets required here range from the simple (using the highlighting or track changes features of Microsoft Word) to the more complex (using NovaMind or OmniGraffle to conceptualize written arguments). These assignments are offered as a sample of the kinds of methods an instructor interested in visual rhetoric might adopt in the classroom in order to bring the techniques of visual analysis and visual processing together with writing pedagogy. Organization Using NovaMind by Catherine Bacon (.pdf download) Outlining Essays Electronically with bubbl.us – A Web-Based Solution by Ty Alyea (.pdf download) Peer Review and Commentary with Microsoft Word by Michelle Jerney-Davis (.pdf download) Text Coloring Assignment by Catherine Bacon (.pdf download) Using NovaMind to Brainstorm for Papers by Liz Jones-Dilworth (.pdf download) Using Track Changes for Peer Review Assignment by Lena Khor (.pdf download) Tags:

Assignments Section Updated

Submitted by timturner on Wed, 2009-04-01 11:58

Thanks to the hard work and creativity of instructors in the Computer Writing and Research Lab here at UT, we at viz. have been able to expand and update the assignments section of our site with a number of new classroom activities oriented around visual rhetoric and culture. If you are looking for new ways to include multimedia, visual, and digital environments in the classroom, or for ways to encourage students to produce multimedia projects of their own, please take a look at the new offerings. First-timers and veterans alike will find a number of great projects. In the coming weeks, we hope to add a few more assignments to the pages, and to that end, we encourage assignment submissions by viz. readers. Have a successful assignment or classroom activity on visual rhetoric and culture that you'd like to share with the world? Please use the contact page to get in touch with our editors. Pending review, your assignment would be posted, with attribution, for other viz. readers to adopt and adapt for their own classes. We would also be interested in hearing about successful tweaks to existing viz. assignments, many of which are designed as templates for implementation in more specific classroom contexts. For example, our friends over at www.auburnmedia.com found a way to tweak the Comparison and Rhetorical Analysis assignment by pairing it with a video about the developing world called "The Other Side of the Coin is Rusting." Visual Rhetoric and Violence IBy Tim Turner (Contact) What is the relationship between rhetoric and violence? Are they mutually exclusive?

The very notion of "good argument" raises questions about what is at stake in the teaching of rhetoric, however. In theory, "good argument" is argument that is persuasive. Taken in this sense, the theoretical and practical concerns of an introductory rhetoric course coincide: instructors teach students how to recognize effective, persuasive arguments written by others ("rhetoric" conceived as a theory of persuasion) and encourage students to model these techniques of effective persuasion in their own writing ("rhetoric" conceived as a practicum in writing). "Goodness" in this context is nonetheless complicated by the ethical stakes of persuasion. People are often persuaded by ethically suspect arguments: arguments that are dishonest, demagogic, or that persuade the listener to engage in morally untenable acts. (Of course, the definition of what constitutes "moral" is itself open to interpretation and, therefore, argumentation; moral critique may be subjected to rhetorical critique.) Yet there is also a connection between ethics and rhetoric in that both "disciplines" insist that one be responsive to the needs of someone else: in rhetoric, this means listening to what the other person has to say (as in the "common ground" model) and responding, sometimes by making concessions, and in ethics, for example, in considering how one's actions will impact others or those situations in which one ought to act to give assistance to others. In both cases, what is implied is a certain claim that the other person makes on me, or that I, in my turn (when I make my argument or when I act in the public sphere) make on them. Both revolve around a certain susceptibility, and this is one reason why the common ground model is attractive: it insists on notions of responsibility, or response-ability, in public, civic life. At the same time, this susceptibility potentially has what we might think of simply as a "dark side": or rather, the abstract susceptibility we have in thinking, in argument and debate, has a physical corollary in our susceptibility to bodily violence--this is susceptibility as vulnerability. In thinking about pedagogical strategies for teaching rhetoric in the past, I have tried to allow these considerations to impact the content in my courses. Most often, this means I have asked students to think about the relationship of violence to rhetoric; about texts that encourage violence; whether, as is sometimes said, violence is what happens when rhetoric fails; and even whether rhetoric itself, the forms of an argument, can be violent. To consider these questions, I have often relied on depictions of violence to conduct such arguments. In my RHE 309 course, the Rhetoric of War and Peace (a topic chosen with many of these questions in mind), these included images of violence including war films, documentaries, and photography. Including such images was not only a way to introduce some of the ethical questions at stake in the teaching of rhetoric. They also had the effect of introducing, often in uncomfortable ways, the visceral into our discussions in a non-gratuitous way. I saw such a strategy as integral to teaching rhetoric in part because persuasion itself is not always only about thought/thinking; it is usually persuasion to action.

Like many of the rhetorical strategies discussed in rhetoric classes, depictions of violence may be said (in general terms) to "move," both literally and figuratively, the audiences to which they are shown or at which they are aimed. Depictions or representations of violence may be deployed as rhetorical strategies, and this point complicates an easy sense that violence and rhetoric are mutually exclusive or that violence is only conceivable as a failure of rhetoric or in the absence of rhetoric.

Agamben's arguments are well worth consideration, but it remains an open question whether such forms of violence are ultimately reducible to purely intellectual analysis. Two issues seem to be at stake here. First, Agamben's work has the benefit of reminding us that violence is sometimes an inescapable part of the public sphere (in popular culture or in political life). He asks us to think critically and carefully about the work of violence, about its meaning and status in everyday life. In short, he asks us to think about what violence is and how it works. He asks us to see its political/civic dimension. At the same time, the potentially affective dimensions of depictions of violence challenge, in useful, productive ways, the notion that violence and rhetoric are "opposites" or mutually exclusive. While the "common ground" model of rhetorical pedagogy privileges or presumes the existence of a civil public sphere, approaches to the teaching of rhetoric that incorporate some discussion of violence offer a "rhetoric-from-the-margins" approach. Incorporating attention to violence, to the visual rhetoric of violence or to violence as visual rhetoric, asks students and instructors to think critically about the constitution of a public sphere in which, ultimately, we are asking our students to responsibly (and response-ably) participate. Questions for assessing the status of violence in the rhetoric curriculum

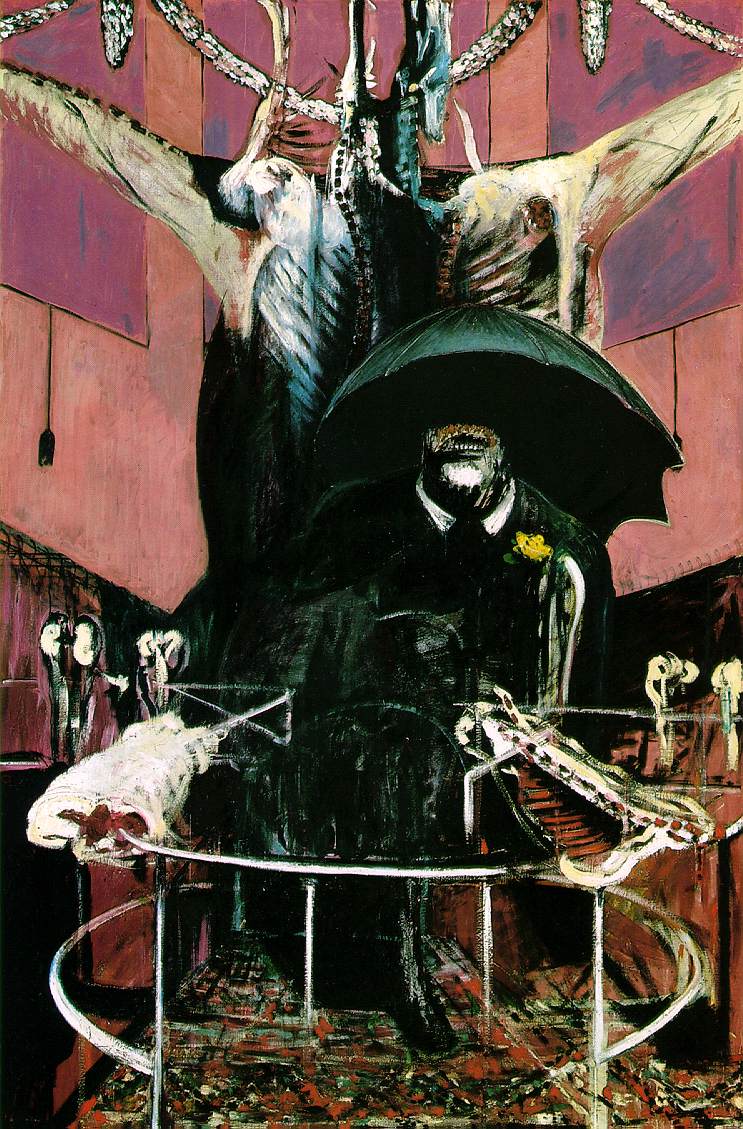

Further ReadingOn the web: In print: Image creditsUpper-right: Francis Bacon, Painting (1946; Museum of Modern Art, New York City) Visual Rhetoric and Violence: PropagandaBy Tim Turner (Contact)

It may, however, be useful to incorporate or implement focused units around these culturally central phenomena that are sometimes marginalized in classroom discussions of rhetoric. In exploring and emphasizing these questions, it may be especially useful to incorporate units on propaganda. These units may include some classical rhetorical theory (Kenneth Burke, "The Rhetoric of Hitler's Battle"), a historical discussion of the use of propaganda in the West in the 20th century (although its history, of course, is much older than that), film screenings of recent documentaries like Control Room or Outfoxed, and formal and informal writing assignments about examples of propaganda. Additionally, units organized to explore the use of propaganda also have the advantage of helping introduce the concepts and vocabulary of visual rhetoric into classroom discussions. Such conversations are useful because they illuminate for students a range of rhetorical possibilities, including the fact that "bad" arguments can be quite influential and that modes of persuasion cannot (and should not) be divorced from ethical considerations. From this perspective, discussions of propaganda may also be useful in that they help illuminate discussions of the fallacies of argument (in which case, "bad" is taken to mean specious, illogical, or poorly reasoned). But discussions of propaganda may also lead to discussions of the ethical dimensions of persuasion (in which case "bad" is taken to mean ethically or morally suspect). A unit on propaganda might have the following structure:

A note about sensitivity issues: many of the historical examples of propaganda in the attached slide show include images of an offensive nature. It is extremely important to foreground their presentation with a careful discussion of the context of these images, as well as disclaimers about offensiveness and, of course, non-endorsement. At the same time, the presentation of such images is in a way precisely the point of such a presentation; however specious, these examples are modes of persuasion that were influential in their way. The point of approaching conversations about rhetoric from the margins, as this discussion of propaganda allows, it to confront the non-civil modes of persuasion that are sometimes employed in ideological contests. Part of what this approach to rhetoric assumes is that such modes of persuasion cannot and should not be ignored. As Burke puts it in his essay on Hitler's Mein Kampf, Here is the testament of a man who has swung a great people into his wake. Let us watch it carefully; and let us watch it . . . to discover what kind of 'medicine' this medicine-man has concocted, that we may know, with greater accuracy, exactly what to guard against, if we are to forestall the concocting of similar medicine in America (191). Further resources on the web: |

viz.

Visual Rhetoric - Visual Culture - Pedagogy

Site informationRecent Blog Posts

|

assignment |

These questions may pose challenges to the prevailing pedagogical models employed in introductory rhetoric classes, which tend to be organized around the "common ground" model of civic or "civil" discourse. As I have

These questions may pose challenges to the prevailing pedagogical models employed in introductory rhetoric classes, which tend to be organized around the "common ground" model of civic or "civil" discourse. As I have  A survey of some of my fellow instructors indicates that while violent images and imagery often form part of the 309 curriculum, the role played by depictions of violence in pedagogical strategy may remain undertheorized. However, the prevalance of such imagery (which may simply be related to the overall prevalence of violence in forms of popular culture) in 309 courses indicates that instructors recognize the pedagogical uses to which violent imagery may be put. One instructor writes, for example, that "Students actually seem drawn to the most violent imagery; it illicits a real response from them. I think that when they see violent imagery they feel compelled to respond." This notion is echoed in the response of another instructor, who writes,

A survey of some of my fellow instructors indicates that while violent images and imagery often form part of the 309 curriculum, the role played by depictions of violence in pedagogical strategy may remain undertheorized. However, the prevalance of such imagery (which may simply be related to the overall prevalence of violence in forms of popular culture) in 309 courses indicates that instructors recognize the pedagogical uses to which violent imagery may be put. One instructor writes, for example, that "Students actually seem drawn to the most violent imagery; it illicits a real response from them. I think that when they see violent imagery they feel compelled to respond." This notion is echoed in the response of another instructor, who writes, Finally, the status of violence in rhetoric classes is further complicated by the potential disruptions of meaning it may impose. More straightforwardly, this analysis begs an important question: what is violence? This may well be a question for definitional argument: how do we, or even how can we, think about, discuss, represent, or understand violence? Recently, for example, this question has especially been an issue in discussions of the Holocaust (as I have discussed in

Finally, the status of violence in rhetoric classes is further complicated by the potential disruptions of meaning it may impose. More straightforwardly, this analysis begs an important question: what is violence? This may well be a question for definitional argument: how do we, or even how can we, think about, discuss, represent, or understand violence? Recently, for example, this question has especially been an issue in discussions of the Holocaust (as I have discussed in  Contemporary introductory rhetoric classes are often (understandably) ordered around the exploration and promotion of the "common ground" model of civic discourse. Students are encouraged to look for continutities among various perspectives in order to demonstrate that they understand and can synthesize various points-of-view. Furthermore, students are encouraged in such pursuits with a particular purpose in mind: so that they might, as a kind of capstone project for any given course, produce well-written, well-reasoned arguments of their own--including fair prolepses demonstrating that they can respect the arguments of their opponents. While in a partisan society this model is both desirable and healthy, it may sometimes foster either a tendency to overlook forms and methods of persuasion that eschew such approaches altogether, or privilege the "civic/civil" discourse surrounding public controversies while ignoring other, perhaps more pervasive forms of rhetoric, such as advertising, "spin," or propaganda.

Contemporary introductory rhetoric classes are often (understandably) ordered around the exploration and promotion of the "common ground" model of civic discourse. Students are encouraged to look for continutities among various perspectives in order to demonstrate that they understand and can synthesize various points-of-view. Furthermore, students are encouraged in such pursuits with a particular purpose in mind: so that they might, as a kind of capstone project for any given course, produce well-written, well-reasoned arguments of their own--including fair prolepses demonstrating that they can respect the arguments of their opponents. While in a partisan society this model is both desirable and healthy, it may sometimes foster either a tendency to overlook forms and methods of persuasion that eschew such approaches altogether, or privilege the "civic/civil" discourse surrounding public controversies while ignoring other, perhaps more pervasive forms of rhetoric, such as advertising, "spin," or propaganda.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago