Site informationRecent Blog Posts

Blog Roll

|

In-class ExerciseVisual Rhetoric and Violence IBy Tim Turner (Contact) What is the relationship between rhetoric and violence? Are they mutually exclusive?

The very notion of "good argument" raises questions about what is at stake in the teaching of rhetoric, however. In theory, "good argument" is argument that is persuasive. Taken in this sense, the theoretical and practical concerns of an introductory rhetoric course coincide: instructors teach students how to recognize effective, persuasive arguments written by others ("rhetoric" conceived as a theory of persuasion) and encourage students to model these techniques of effective persuasion in their own writing ("rhetoric" conceived as a practicum in writing). "Goodness" in this context is nonetheless complicated by the ethical stakes of persuasion. People are often persuaded by ethically suspect arguments: arguments that are dishonest, demagogic, or that persuade the listener to engage in morally untenable acts. (Of course, the definition of what constitutes "moral" is itself open to interpretation and, therefore, argumentation; moral critique may be subjected to rhetorical critique.) Yet there is also a connection between ethics and rhetoric in that both "disciplines" insist that one be responsive to the needs of someone else: in rhetoric, this means listening to what the other person has to say (as in the "common ground" model) and responding, sometimes by making concessions, and in ethics, for example, in considering how one's actions will impact others or those situations in which one ought to act to give assistance to others. In both cases, what is implied is a certain claim that the other person makes on me, or that I, in my turn (when I make my argument or when I act in the public sphere) make on them. Both revolve around a certain susceptibility, and this is one reason why the common ground model is attractive: it insists on notions of responsibility, or response-ability, in public, civic life. At the same time, this susceptibility potentially has what we might think of simply as a "dark side": or rather, the abstract susceptibility we have in thinking, in argument and debate, has a physical corollary in our susceptibility to bodily violence--this is susceptibility as vulnerability. In thinking about pedagogical strategies for teaching rhetoric in the past, I have tried to allow these considerations to impact the content in my courses. Most often, this means I have asked students to think about the relationship of violence to rhetoric; about texts that encourage violence; whether, as is sometimes said, violence is what happens when rhetoric fails; and even whether rhetoric itself, the forms of an argument, can be violent. To consider these questions, I have often relied on depictions of violence to conduct such arguments. In my RHE 309 course, the Rhetoric of War and Peace (a topic chosen with many of these questions in mind), these included images of violence including war films, documentaries, and photography. Including such images was not only a way to introduce some of the ethical questions at stake in the teaching of rhetoric. They also had the effect of introducing, often in uncomfortable ways, the visceral into our discussions in a non-gratuitous way. I saw such a strategy as integral to teaching rhetoric in part because persuasion itself is not always only about thought/thinking; it is usually persuasion to action.

Like many of the rhetorical strategies discussed in rhetoric classes, depictions of violence may be said (in general terms) to "move," both literally and figuratively, the audiences to which they are shown or at which they are aimed. Depictions or representations of violence may be deployed as rhetorical strategies, and this point complicates an easy sense that violence and rhetoric are mutually exclusive or that violence is only conceivable as a failure of rhetoric or in the absence of rhetoric.

Agamben's arguments are well worth consideration, but it remains an open question whether such forms of violence are ultimately reducible to purely intellectual analysis. Two issues seem to be at stake here. First, Agamben's work has the benefit of reminding us that violence is sometimes an inescapable part of the public sphere (in popular culture or in political life). He asks us to think critically and carefully about the work of violence, about its meaning and status in everyday life. In short, he asks us to think about what violence is and how it works. He asks us to see its political/civic dimension. At the same time, the potentially affective dimensions of depictions of violence challenge, in useful, productive ways, the notion that violence and rhetoric are "opposites" or mutually exclusive. While the "common ground" model of rhetorical pedagogy privileges or presumes the existence of a civil public sphere, approaches to the teaching of rhetoric that incorporate some discussion of violence offer a "rhetoric-from-the-margins" approach. Incorporating attention to violence, to the visual rhetoric of violence or to violence as visual rhetoric, asks students and instructors to think critically about the constitution of a public sphere in which, ultimately, we are asking our students to responsibly (and response-ably) participate. Questions for assessing the status of violence in the rhetoric curriculum

Further ReadingOn the web: In print: Image creditsUpper-right: Francis Bacon, Painting (1946; Museum of Modern Art, New York City) Visual Rhetoric and Violence: PropagandaBy Tim Turner (Contact)

It may, however, be useful to incorporate or implement focused units around these culturally central phenomena that are sometimes marginalized in classroom discussions of rhetoric. In exploring and emphasizing these questions, it may be especially useful to incorporate units on propaganda. These units may include some classical rhetorical theory (Kenneth Burke, "The Rhetoric of Hitler's Battle"), a historical discussion of the use of propaganda in the West in the 20th century (although its history, of course, is much older than that), film screenings of recent documentaries like Control Room or Outfoxed, and formal and informal writing assignments about examples of propaganda. Additionally, units organized to explore the use of propaganda also have the advantage of helping introduce the concepts and vocabulary of visual rhetoric into classroom discussions. Such conversations are useful because they illuminate for students a range of rhetorical possibilities, including the fact that "bad" arguments can be quite influential and that modes of persuasion cannot (and should not) be divorced from ethical considerations. From this perspective, discussions of propaganda may also be useful in that they help illuminate discussions of the fallacies of argument (in which case, "bad" is taken to mean specious, illogical, or poorly reasoned). But discussions of propaganda may also lead to discussions of the ethical dimensions of persuasion (in which case "bad" is taken to mean ethically or morally suspect). A unit on propaganda might have the following structure:

A note about sensitivity issues: many of the historical examples of propaganda in the attached slide show include images of an offensive nature. It is extremely important to foreground their presentation with a careful discussion of the context of these images, as well as disclaimers about offensiveness and, of course, non-endorsement. At the same time, the presentation of such images is in a way precisely the point of such a presentation; however specious, these examples are modes of persuasion that were influential in their way. The point of approaching conversations about rhetoric from the margins, as this discussion of propaganda allows, it to confront the non-civil modes of persuasion that are sometimes employed in ideological contests. Part of what this approach to rhetoric assumes is that such modes of persuasion cannot and should not be ignored. As Burke puts it in his essay on Hitler's Mein Kampf, Here is the testament of a man who has swung a great people into his wake. Let us watch it carefully; and let us watch it . . . to discover what kind of 'medicine' this medicine-man has concocted, that we may know, with greater accuracy, exactly what to guard against, if we are to forestall the concocting of similar medicine in America (191). Further resources on the web: Mac vs. PC in the classroom

Submitted by erinhurt on Mon, 2007-10-08 15:43

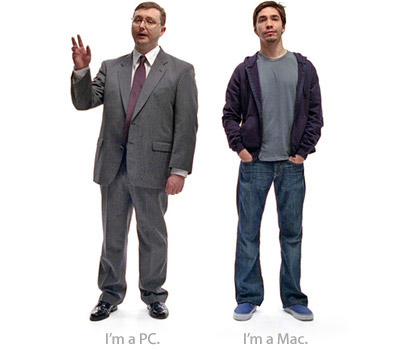

When teaching a rhetoric course, I love to use the Apple Commercials to show my students an example of real-world ethos.

Visual Rhetoric Writing Exercise

Submitted by Nate Kreuter on Mon, 2007-04-16 09:56

I recently incorporated the Garry Winogrand photo below into an in-class writing exercise. The exercise is essentially the same as one that I came up with when helping Brooks Landon teach his Prose Style course at the University of Iowa a few years ago. Keep reading to learn more about the writing exercise.

I bring a photo in to class, usually one that depicts something weird, something that probably has a story behind it but that doesn't make that story explicit. I project the photo and don't tell the students a word about it, not when it was taken, by whom, nothing. Then the students have to write about the photo. It's a creative assignment and in this case I was trying to get them to think about form. Specifically, after a workshop on the subject in the prior class, I was asking them to write "cumulative" sentences. Cumulative sentences, for those of you who aren't prose style junkies, are described in Francis Christensen's essay "A Generative Rhetoric of the Sentence." So, the photo was just a prompt to get the students writing in a new mode that we had been working on. The exercise went very well and my students generated some whacky, but stylistically adventurous, prose. If I get their permission, I will post some of their writings in the comments soon. In-class OmniGraffle assignmentNotes for the Instructor: This assignment is designed to introduce students to OmniGraffle and give them practice in using it. However, instructors may also tweak the assignment to achieve specific goals related to the course; for example, OmniGraffle is an excellent resource for, among other things, brainstorming ideas for paper topics, or thinking about structure and organization in writing (it presents a more flexible, visually-organized model than, for example, a “Roman-numeral” outline). It can also be used to complement reading exercises as a way to “visualize” how arguments or texts are constructed. This assignment asks students to take specific set of topics, or topoi, (selected either by the students or by the instructor), and map them, creating a visual representation of the various connections between ideas. Instructors can plan on using one full class period to work on this project, at the end of which students can submit their maps to the teacher folder saved as .pdf files. As points of reference, you can see one example on this page, and another example is attached. PowerPoint 101Notes for the Instructor: This assigment is designed to introduce students to Microsoft's PowerPoint presentation software. Students are asked to work in groups and create presentations related to the content of the course (the instructor may wish to generate a list of acceptable topics). This assignment is designed to last no more than 2 or 3 class meetings: students will choose (or be assigned) their groups and topics, work on the presentations outside of class, and then present them to their peers. Students are also asked to submit a two-page paper describing the process of working on the project; instructors may choose to tweak this aspect of the assignment according to the goals of the course. Assignment Description: Becoming familiar with PowerPoint Category: Group project Goals: This project is designed to introduce students to Microsoft’s PowerPoint software and give them practice in using it by producing an organized presentation to be given in class. Tasks:

Guidelines:

Suggestions: Groups will be given some time to work on their projects in class, but are also expected to meet at least once outside of class to discuss the topic, plan the presentation, and divide different responsibilities among members of the group. |

viz.

Visual Rhetoric - Visual Culture - Pedagogy

Site informationRecent Blog Posts

|

In-class Exercise |

These questions may pose challenges to the prevailing pedagogical models employed in introductory rhetoric classes, which tend to be organized around the "common ground" model of civic or "civil" discourse. As I have

These questions may pose challenges to the prevailing pedagogical models employed in introductory rhetoric classes, which tend to be organized around the "common ground" model of civic or "civil" discourse. As I have  A survey of some of my fellow instructors indicates that while violent images and imagery often form part of the 309 curriculum, the role played by depictions of violence in pedagogical strategy may remain undertheorized. However, the prevalance of such imagery (which may simply be related to the overall prevalence of violence in forms of popular culture) in 309 courses indicates that instructors recognize the pedagogical uses to which violent imagery may be put. One instructor writes, for example, that "Students actually seem drawn to the most violent imagery; it illicits a real response from them. I think that when they see violent imagery they feel compelled to respond." This notion is echoed in the response of another instructor, who writes,

A survey of some of my fellow instructors indicates that while violent images and imagery often form part of the 309 curriculum, the role played by depictions of violence in pedagogical strategy may remain undertheorized. However, the prevalance of such imagery (which may simply be related to the overall prevalence of violence in forms of popular culture) in 309 courses indicates that instructors recognize the pedagogical uses to which violent imagery may be put. One instructor writes, for example, that "Students actually seem drawn to the most violent imagery; it illicits a real response from them. I think that when they see violent imagery they feel compelled to respond." This notion is echoed in the response of another instructor, who writes, Finally, the status of violence in rhetoric classes is further complicated by the potential disruptions of meaning it may impose. More straightforwardly, this analysis begs an important question: what is violence? This may well be a question for definitional argument: how do we, or even how can we, think about, discuss, represent, or understand violence? Recently, for example, this question has especially been an issue in discussions of the Holocaust (as I have discussed in

Finally, the status of violence in rhetoric classes is further complicated by the potential disruptions of meaning it may impose. More straightforwardly, this analysis begs an important question: what is violence? This may well be a question for definitional argument: how do we, or even how can we, think about, discuss, represent, or understand violence? Recently, for example, this question has especially been an issue in discussions of the Holocaust (as I have discussed in  Contemporary introductory rhetoric classes are often (understandably) ordered around the exploration and promotion of the "common ground" model of civic discourse. Students are encouraged to look for continutities among various perspectives in order to demonstrate that they understand and can synthesize various points-of-view. Furthermore, students are encouraged in such pursuits with a particular purpose in mind: so that they might, as a kind of capstone project for any given course, produce well-written, well-reasoned arguments of their own--including fair prolepses demonstrating that they can respect the arguments of their opponents. While in a partisan society this model is both desirable and healthy, it may sometimes foster either a tendency to overlook forms and methods of persuasion that eschew such approaches altogether, or privilege the "civic/civil" discourse surrounding public controversies while ignoring other, perhaps more pervasive forms of rhetoric, such as advertising, "spin," or propaganda.

Contemporary introductory rhetoric classes are often (understandably) ordered around the exploration and promotion of the "common ground" model of civic discourse. Students are encouraged to look for continutities among various perspectives in order to demonstrate that they understand and can synthesize various points-of-view. Furthermore, students are encouraged in such pursuits with a particular purpose in mind: so that they might, as a kind of capstone project for any given course, produce well-written, well-reasoned arguments of their own--including fair prolepses demonstrating that they can respect the arguments of their opponents. While in a partisan society this model is both desirable and healthy, it may sometimes foster either a tendency to overlook forms and methods of persuasion that eschew such approaches altogether, or privilege the "civic/civil" discourse surrounding public controversies while ignoring other, perhaps more pervasive forms of rhetoric, such as advertising, "spin," or propaganda.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago