Charles Burnett’s little known and nearly plotless masterpiece, Killer of Sheep, offers a tender yet realistic vision of life in 1970s Watts, the racially segregated suburb of Los Angeles where poverty, racism, and riots doomed the area to generations of social and economic oblivion. Inspired by Italian neo-realism, Burnett’s camera lingers on characters—many played by non-actors—to reveal situations of familial intimacy and communal identification.

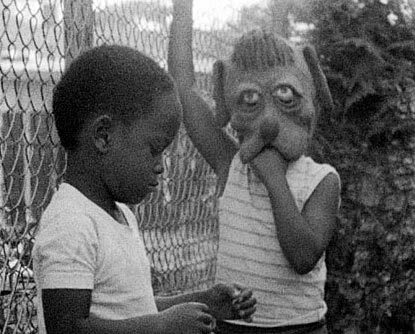

An opening scene shows a young girl in the mask of a dog. Such expressive sadness in the features of the animal hides the perceptive eyes and facial gestures of the child. Her father, Stan (played by Henry Gayle Sanders), exhausted from working shifts at a Los Angeles slaughterhouse, lays linoleum on the kitchen floor. A sensitive man, burdened with domestic duty and physical labor, Stan’s story offers occasion for audiences to reflect on the dislocation of his desire from the circumstances of his life.

Other images show children at play in an urban debris field; a young man casually walks away with a television set; children act out and are disciplined; petty gangsters arrive to tempt Stan to join them in a robbery. But the central narrative focuses on Stan and his relationship to his family and community.

This emotionally complex film, however, argues for the ambiguity of Stan’s relation to others—particularly his wife, with whom sexual intimacy is a problem. Attempts to help friends, too, often result in mishap, such as when Stan helps purchase a new engine block, only to have it fall out of the back of his pick-up as he puts it in gear. Stan’s main joy in life seems, in fact, to come through his work at the slaughterhouse, ushering sheep along to their final moments before the processing of their flesh.

Made on a budget of only $10,000 while he was a student at UCLA, Burnett’s film doesn’t try to ameliorate Stan’s situation. Instead, he argues for a vision of reality that refuses to perform to the social and racial expectations of others. He shows us, instead, a strange beauty that, perhaps against the viewer’s will, refuses to correspond to an appropriate system of values. Such tension brings viewers into a film that also denies the urgency of a crafted message, documenting instead the motives of communal actors. The final scene—a baby shower for a young pregnant woman—could have pushed the narrative into sentimentality (Spike Lee, for instance, can’t seem to live without it). Instead, viewers witness an exchange of human forces. Although we are not in the realm of Longinus’ sublime, the neo-realistic narrative nonetheless argues for a human vision that transcends social and economic behavior.

Listed in the Library of Congress’ National Film Registry and rated by the National Society of Film Critics as one of the top films of all time, Killer of Sheep is an American treasure, despite only recently acquiring the attention it deserves.

Comments

George Washington

Thanks for the post: I remember reading about KoS when it was rereleased last year, but I haven’t had a chance to see it yet. Each time I’ve read about it, though, the descriptions have reminded me of David Gordon Green’s George Washington, a fantastic, lyrical film about children in North Carolina. The child wearing the mask in the image you posted reminds me of a similar image from that film:

Here's the trailer:

John, thanks for directing me

John, thanks for directing me to George Washington. I haven't heard anything about. I wonder if the GW mask is a nod in some way to Burnett's film?

I think so. The liner notes

I think so. The liner notes to the Criterion DVD list Killer of Sheep as an influence, along with Days of Heaven and A Day with the Boys.

Days of Heaven

I'll have to see this film. Days of Heaven is magnificent. I used it in teaching my rhetoric of courtship class--but it covers a lot of other territory. It's good to know others refer to Malick's masterpiece.

Thanks--Dale