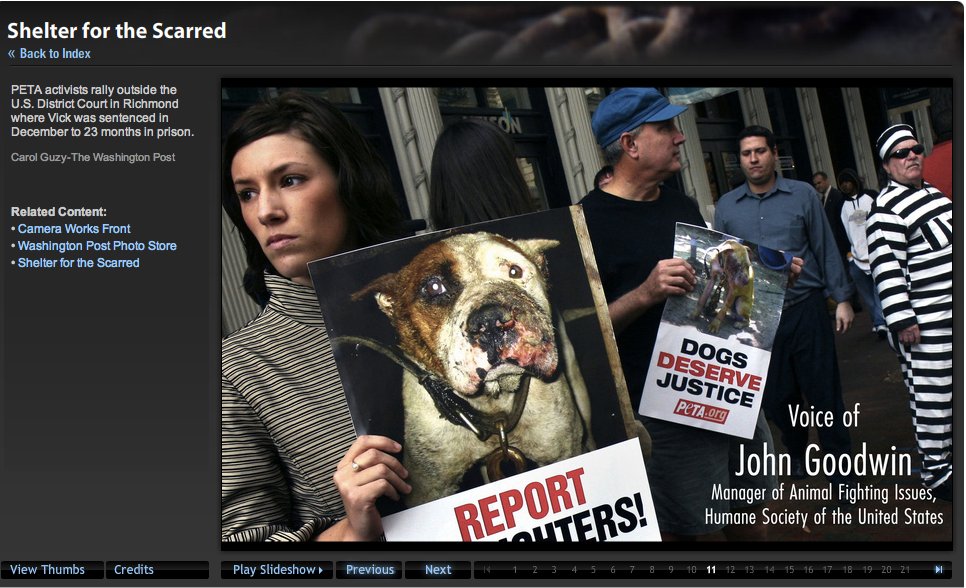

Screen shot of narrated slide show, Shelter for the Scarred

featured on Washington Post website

Photographer: Carol Guzy

This past week the Supreme Court heard oral arguments considering the constitutionality of U.S. v. Stevens, a case that makes it a federal crime to make and sell visual images of animal cruelty. Although originally created by Congress to curb the market for "crush videos"--images of people in high heel shoes stomping on small animals for the purposes of titillating the viewer--the statute contains language so vague that it led the justices to propose a slew of bizarre hypotheticals ranging from the artistic value of images of force-feeding fowl for foie gras to the possibility of a pay-per-view human sacrifice channel. Now I have to admit that I am slightly shaky on all of the legal issues at stake here, but this transcript of the oral arguments certainly made for some interesting reading. Moreover, and not surprisingly, many of the questions raised within the oral arguments align with issues we often consider with respect to documentary studies and visual culture.

At several points within the discussion the justices probed the question of whether the presence of the camera, or the act of taking the picture encouraged the violent action documented. Or conversely, they considered whether classifying images of animal cruelty as unprotected free speech might dry up the market for the images and thus reduce the instances of violent conduct. Justice Scalia pressed Deputy U.S. Solicitor General Neal Katal to distinguish between the attempt to limit the activity (dog-fighting or crushing small animals) from the attempt to prevent communication about those acts (images of dog-fighting or images of small animals being crushed). Katal linked his argument to an earlier decision in New York v. Ferber in which the Supreme Court ruled that child pornography is not protected under the First Amendment. Justice Ginsburg suggested that Mr. Stevens was only filming the dog-fighting and that the fighting would occur whether or not he was present whereas the "simultaneous abuse of the child, it occurs only because the picture is being taken." She went on to urge Mr. Katal to confront that "the very taking of the picture is the offense. That is the abuse of the child" (Transcript, 25). This line of argument prompted several key questions about whether the images of animal cruelty were staged solely for the camera--a set of questions that is often posed about the ethical obligations of photo-journalists and documentary filmmakers.

For me, one of the most intriguing moments in the oral arguments, however, occurred when Justice Scalia chastised Lawyer Patricia Millet for engaging with the language of the statute that provides for exception in the case of educational, artistic, journalistic, or scientific depictions. Justice Scalia notes, "I really think you should focus not on the educational value for -- to make people hate bullfighting and things, but on quite the opposite, it seems to me. On the right under the First Amendment of people who like bullfighting , who like dog-fighting, who like cock-fighting, to present their side of -- of the debate" (Transcript, 45). One of the key components here is the multivalent nature of images of, say, dog-fighting. These images--as Ms. Millet pointed out--can be used by documentary filmmakers or by PETA activists as in the images above to argue against dog-fighting but--as Justice Scalia indicates--may also be used by advocates for the activity. In fact, because of the slippery nature of the caption, the very same images can be used to argue any number of interpretations. And they were in this instance--Mr. Stevens argued his images were historical and had value as documentary. The jury saw otherwise.

While the vague wording of the statute will probably lead to its being overturned, it also led to some fascinating moments in which the justices tested the legal limits of the language. In addition to the gripping discussion about whether the depiction of modern men and women dressed as gladiators fighting to the death would hold historical value, the court also considered the distinction between images of dog-fighting and staged images of dog-fighting. After mulling over these debates about the reality of the referent, the justices considered whether there was a difference, more generally, between images of violence and images of simulated acts of violence. This discussion continued until the question was raised whether images of violence lead to an increase in the number of incidents of violence within a community. And this point brought the court back to the consideration of whether regulating the image will restrict the act depicted and whether restricting the act depicted justifies restricting free speech.

There is more to be had within the transcript for scholars of visual studies and we'll hear more from the justices when their decision is released in a few weeks.

Comments

Thanks!

Great post. Stephen Colbert had some great commentary of the Supreme Court's deliberations: http://www.colbertnation.com/the-colbert-report-videos/251993/october-07-2009/human-sacrifice-channel