Image Credit: Red Scare archive

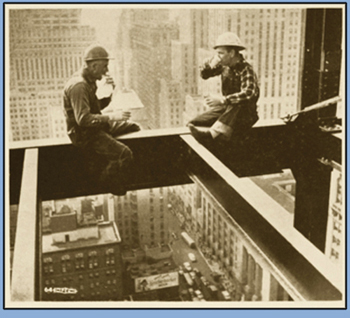

The image above-- an anti-labor cartoon claiming that the sloth of American workers (who only want to work a measly 8 hours a day and spend the rest of the day lounging with their pipes) was endangering American competitiveness with Weimar Germany (and we know how well things worked out for them)-- could serve as "exhibit A" in the argument that entrenched interests never view ANY concession as reasonable. The 8-hour work day has by now become such a sacred cow in American society that it seems almost natural, but the 8-hour day did not spring up miraculously on the 8th day of creation. Along with many other rights and protections that we currently take for granted, it was the result of a decades-long struggle of workers against the egregious abuses of industrial captial in the heady days of its American youth. "Exhibit A" comes from Red Scare, an image database hosted by the City University of New York that documents the social upheaval of 1918-1921. Digital archives like Red Scare and Labor Arts preserve and present a history of America's labor movement through photographs, cartoons, fliers, songbooks and other visual artifacts.

When Noel asked us to prepare for the upcoming Best Practices workshop by blogging on digital archives, I immediately volunteered to cover archives focusing on labor. While this may seem like http://viz.dwrl.utexas.edu/node/522/edita departure from my typical posts on food and food politics, the history of our American food system from Upton Sinclair's The Jungle to the ongoing federal anti-trust investigation of Monsanto is inextricably linked with the history of labor. Contemporary concerns about food safety and quality cannot afford to ignore the labor conditions that underly the production of so-called "cheap" food. We cannot respect the food we buy, prepare and consume if we do not respect the men and women whose labor brings it out of the common earth.

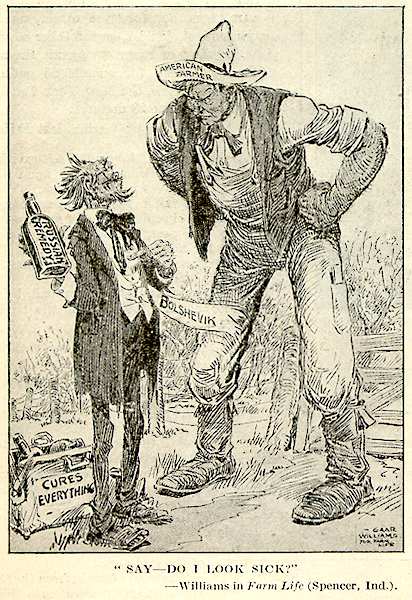

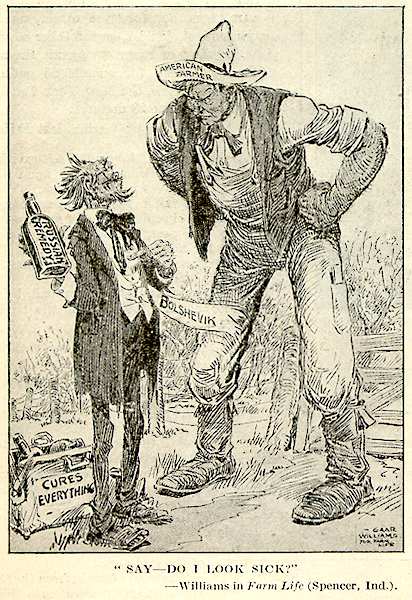

This connection between labor and food is too often overlooked in the general divide between rural and urban interests (the country and the city). This cartoon from 1919 uses cliched images of bucolic country vitality and sickly urban scheming to enhance a nationalist argument that American farmers have nothing to gain from the "foreign" snake-oil of organized labor. These are, of course, the same share-croppers and dry-land farmers who would in the next decade be forced from their land by drought and abject poverty (many of whom became "Okies" who were later exploited in California labor camps).

Image Credit: Red Scare

Both Red Scare (hosted by CUNY's Newman Library) and Labor Arts (hosted by NYU's Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives) have explicitly pedagogical missions and are readily adaptable for use in the rhetoric classroom. Neither site offers images of sufficient size and quality to be useful in original research, but the images are well within the range of acceptible quality for an undergraduate class (Red Scare includes this technical note: "As they were all meant to serve as "reference"

copies accessible via the Web, it was thought this quality of scan would

be sufficient." Labor Arts includes some images of a substantially higher quality, but the overall size and quality of images is uneven).

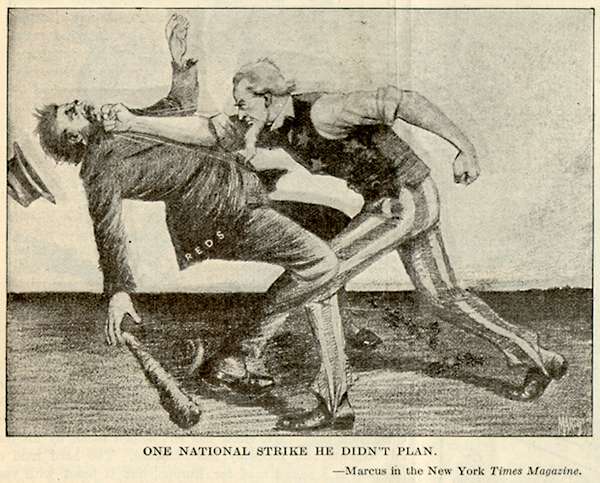

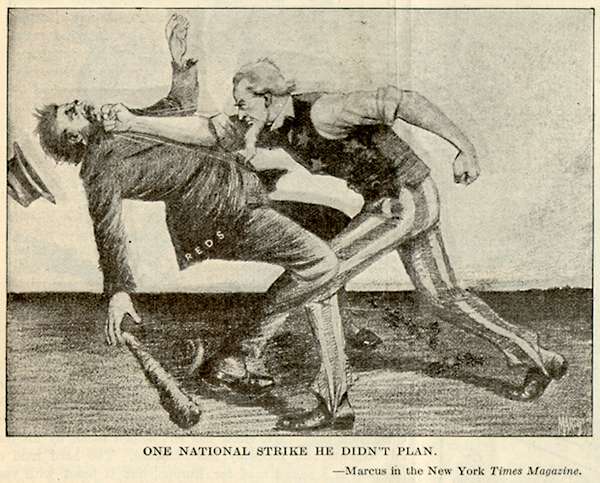

Red Scare doesn't offer a search function, but the images are organized in heavily cross-referenced chronological and subject indexes; it also includes a brief guide to finding images in the archive. I had no problems finding images related to particular themes and subjects, and I stumbled on a lot of interesting material in the process. For instance, I clicked the "related images" link for one cartoon using Uncle Sam and was redirected to a page with all the archives Uncle Sam cartoons, including this gem from 1920.

Image Credit: Red Scare

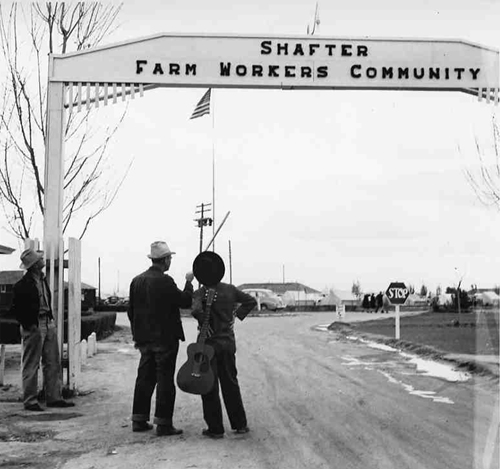

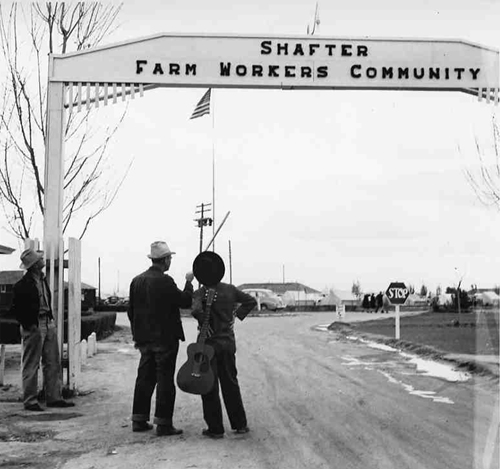

Labor Arts organizes its images within "Collections" and "Exhibits." The "Collections" page lets users browse images organized by medium (buttons, photographs, pamplets, etc), theme ("civil rights," "strikes," "workers at work," etc.) or time period. The "Exhibits" present the same images collected in museum-like exhibitions about, for example, the Wobblies, Social Documentary Photography or Labor songbooks. Labor Arts also offers a fairly flexible search function; you can search for something as broad as a keyword or as narrow as an item number, and you can refine searches by organizaiton, occupation, date, ethnicity and several other criteria. A search for "farm" turned up twenty entries that included UFW posters, a "5 cents for fairness" button supporting strawberry pickers, and this picture of Woody Guthrie visiting a farm camp in 1941.

Image Credit: Labor Arts

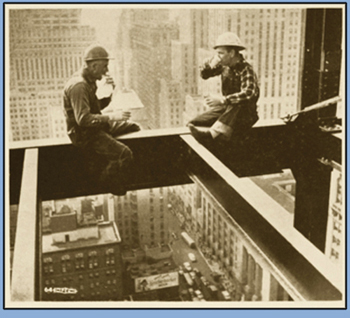

In both its "Collections" and its "Exhibits," Labor Arts provides a substantial amount of relevant context for each image. For instance, this 1935 photograph of striking office workers is accompanied by text which points out that "had only recently won legal protection for their right to organize,

with the passage of Roosevelt's National Industrial Recovery Act in

1933. The Act's famous Section 7(a) recognized for the first time the

right of workers to organize into unions of their own choosing to

represent their interests."

Image Credit: Labor Arts

This kind of context (along with the broad scope of the collection and its ease of use) make Labor Arts a potentially useful pedagogical tool for classroom use or undergraduate research. The fact that the archive is supported financially by several labor unions could raise questions of objectivity, but I don't see any problems that couldn't be addressed with a brief class discussion on intellectually honest use of clearly biased material (a topic that most rhetoric instructors will probably want to discuss with their students anyways).

Either archive is worth exploring and provides links to other similar resources. I am personally looking forward to digging deeper in the Labor Arts archive, but, for now, I'm off to lunch.

Image Credit: Labor Arts

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago