Meet Diversity: American Girl's Samantha Parkington and "Radical" Politics

In an April 2013 opinion post for The Atlantic, feminist journalist Amy Schiller brought dolls to the forefront of girls’ feminist activism by announcing, “American Girls Aren’t Radical Anymore.” Citing Mattel Incorporated’s takeover in 1998 of Pleasant company, the American Girls’ original home, as a main source of the shift in the dolls’ political and socioeconomic messages, Schiller complains of the company’s shifting focus from the historical characters that were so familiar to many American girlhoods and toward “Girl of the Year” dolls and dolls designed to look especially like each customer.

Image Credit: American Girl

Schiller’s assessment is an astute one; a brief look at the American Girls website, where the casual observer now has to go out of her way to even locate the historical American Girls, shows how far Mattel has shifted its focus away from the historical characters and toward the most effective consumer products.

Image Credit: American Girl

But the American Girls are not only dolls, as Schiller mentions; in fact, her argument largely rests on examples of the “Radical” politics of early American Girls, such as Samantha Parkington’s growing awareness of socioeconomic tension in Samantha Learns a Lesson, the second novel in Samantha’s series. Schiller’s argument, however, begs the question: were the American Girls ever really radical?

Consider Samantha herself. In her opening book, Meet Samantha, the girl-slash-doll first encounters child labor, learns that her black seamstress is socially required to live in the “colored part of town,” and donates her doll to her underprivileged friend. Perhaps Pleasant Company should have titled the book Meet Diversity—because it functions in an unusual generic position—it is simultaneously fiction (traded at public libraries across the country), prop sold with the doll itself, and nonfiction primer on diversity. Indeed, the novel is tightly plotted to convey a clear socioeconomic message: Samantha has been sheltered in the Edwardian household of her old-school Victorian grandmother, and she has no cultural experience with the world outside her white, aristocratic, angel-in-the-house lifestyle. That Samantha comes into contact with these shifting social realities does indeed seem to illustrate Schiller’s point that the old-school American Girls (Samantha was one of the original three dolls—and books—to be released by the company in 1986) advocated more radical politics of equality than those of the company’s current agenda.

And, certainly, Pleasant Company’s early products are leaps and bounds ahead of most girls’ toys of that era and our own. In questioning the politics of “Diversity” in Samantha’s early stories, I don’t mean to reduce what is undeniably an effort at offering girls productive, educational, and politically equitable toys and reading material. To be clear: that the American Girl Company not only uses historical fiction to draw girls’ attention to the cultural position of girlhood across American history, but also does so by deliberately weaving together the stories of girls of color, of child laborers, of politically active adolescents, and of immigrants is no small feat, and I certainly do not want to equate the franchise with, say, Mattel’s other economic flagship, Barbie.

Image Credit: Mattel

At the same time, we've had some recent cultural attention paid to girls toys. For example, Goldie Blox produces the system of engineering toys made for girls and sold in colors other than pink:

Image Credit: Goldie Blox

This trend demands an examination of where the American Girl's “landmark” of radical girlhood politics really stands, before we can quite embrace it as the paradigm of girls’ toys sadly corrupted by more profitable product placement. In other words, “better than Barbie” may not be our best benchmark.

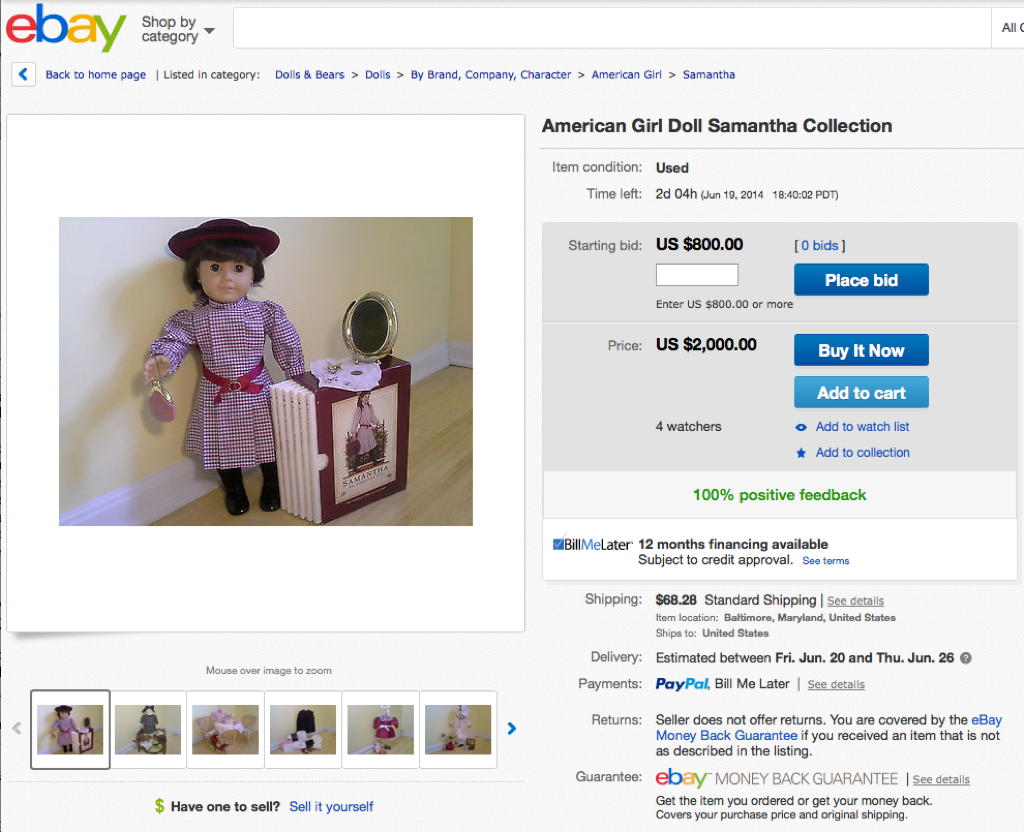

I wonder, for example, how far the message of socioeconomic privilege awareness Schiller briefly traces in Samantha Learns a Lesson really goes when the doll-character was sold for upwards of ninety dollars and is now available only on eBay, sometimes for thousands of dollars? It wouldn’t have been at all difficult to spend a thousand dollars on Samantha paraphernalia and still not complete the set.

Image Credit: eBay

Image Credit: eBay

Conversely, Meet Samantha and other books in both Samantha’s series and the franchise as a whole have been wildly popular at public libraries—suggesting obliquely that children from wide socioeconomic backgrounds have access to and enjoy the books. (My own copy, purchased used from Amazon, appears to have been well-loved by a few girls.) At the same time, the material pairing of the novels with the doll and her dozens of accessories troubles the narrative of radical politics Schiller mourns. In short, the text of the books gestures broadly toward radicalism, but undercuts its own message by fusing the text with not only the dolls and paraphernalia, but also with clothing and games for the girls themselves. This multi-textuality makes the books something of a unique phenomena in childhood culture, so that Samantha simultaneously does the important cultural work of advocating social awareness while placating nascent white guilt and the potential for girls to engage with social change. The doll culture—the clothes, the pink, the goal of getting a doll that looks just like me troubles the “radical” politics of the actual story. In other words, the message of the text is at odds with the visual representation of the doll spectacle. While the language of the novel teaches Samantha that not all girls were born with her level of white, wealthy privilege, the excessive detail on the clothes, advertising that scripts girls to complete Samantha’s “set,” and the in-text illustrations of dolls that represent the actual, purchase-able doll give the lie to Schiller’s fantasy that American Girl Dolls were ever truly radical.

Add new comment