“Kids These Days”: The Not-at-all New Phenomenon of Fashionable Childhood Sexualization

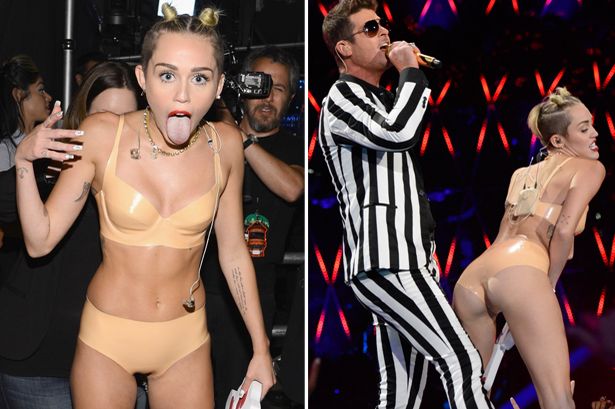

Last year, when Miley Cyrus gave us this delight:

Image Credit: Mirror

the interwebs exploded with home critics—often sloppy analyses of Cyrus’s performance, rife with moral judgment and fear for the future. The outrage regards not whether the singer is talented, or whether her show was successful, but over her behavior, and, especially, her clothing.

Of course, a large part of this reaction to the VMA show was due to the “weirdness” of Cyrus’s dances-with-bears schtick. Still, we’d be naive to overlook the role of her clothes in this kind of backseat judgment. Many of the blog posts, op-eds, and social media comments linked the VMA performance with Cyrus’s then-new video, “Wrecking Ball,” pointing out the “provocative” dress as a sign of the girl’s unstable nature or corrupted innocence. “Where is Hannah Montana?” these articles bemoaned. The issue seems to be not only the amount of skin shown, but that Cyrus is a girl dressed too maturely.

Image Credit: Wikipedia

I don’t want to reduce all the pushback here to Cyrus’s age. Of course, this little blowup raises interesting questions about the public performance of one’s sexuality, about an artist’s attempt to transition from child to adult, about the public’s need to police her body. All of those concerns, I take as the given subtext of this kind of event. I’d like to focus, specifically, on the way that this issue has been framed as a kind of violation of maturity, wherein the clothes represent a certain age category, one many audiences see as inconsistent with the performer’s actual—or “appropriate”—level of maturity.

Actually, this kind of link between clothing and age is a strange inverse of what M. Gigi Durham calls the “Lolita Effect,” “a construction of sexuality that both exploits and limits sexual expression and agency, and is deliberately focused on young girls.” Here, sex is associated with youth, and young bodies are then co-opted both to support the demands of sexual management and to mobilize standards for older women as well. We see this effect both in the way the Toddlers in Tiaras are dressed as much older, hyper sexualized women and in the way older women are then infantilized. For example:

Image Credit: Oh No They Didn't

Image Credit: Stop Toddlers and Tiaras

Here, we’re outraged because these toddlers are dressed up as women. We cannot tolerate the concept of child sexuality—despite the fact that every solid study on childhood development acknowledges it. On the other hand, these:

Image Credit: Steven Meisel

Image Credit: Steven Meisel

Image Credit: Steven Meisel

Image Credit: Steven Meisel

Madonna did this photoshoot for Vanity Fair in 1992. The public seems to have a love-hate relationship with these images. They serve up female bodies; fashion facilitates the role of the viewer as couch critic, so that we can all bemoan the downhill spiral of the way “Society” is going these days. I think it’s important to include Madonna in this discussion not only because these images offer a counterpart to Toddlers & Tiaras, but also because they remind us that this phenomenon is not in any way new. Durham, for example, charts a whole series of sexualized girls (JonBenet Ramsey, Brooke Shields, The Little Mermaid...). Here, more than two decades ago, we have Madonna performing hyper sexualized girlhood through a fashion shoot. The adult female is sexy because she’s childish. So all of these panicked responses to Miley, the fear-mongering that suggests we have somehow crossed a threshold in the female sex/fashion industry, might do well to remember, as Don Draper tells us in another blithely misogynist episode (s01e04) of Mad Men: “Maybe every generation thinks the next one is the end of it all. Bet there are people in the Bible walking around, complaining about kids today."

Add new comment