Image Credit: Wikipedia

I’m a bit nervous and distracted right now, as I’m in the middle of preparing to go to Ottawa for the CSECS/NEASECS conference this weekend, and anticipating the following weekend’s jaunt to St. Louis for the MMLA Conference. My plan to manage to stress involves using my blog posts for the next two weeks to examine my paper topics through the lens of visual rhetoric.

For the CSECS/NEASECS conference, I’m going to be presenting a paper on Adam Smith and Edmund Burke entitled “Fragmentary Selves: (Aesthetic) Living with the Man in the Breast in The Theory of Moral Sentiments.” While the title may be overlong, it’s in part because I’m trying to balance within the paper a discussion of the Burkean sublime and how Smith uses that aesthetic rhetoric to discuss and picture an ideal self that is so responsive to the feelings of others that such a self is in part fragmented by this openness. The connection that I see between this paper and my work here at viz. is through the trope of ruins.

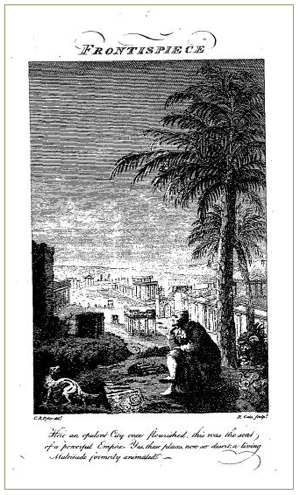

Ruins, as I’ve mentioned previously on this blog, were a huge obsession of the eighteenth century. The Victoria and Albert Museum website describes the place of ruins in eighteenth-century landscape painting as aesthetic objects, in particular examining the work of William Gilpin. Ruins are also important as signs of empire: both the fallen Roman Empire whose writers people like Pope tried to emulate, and the emergent British Empire whose rise would be documented by writers like James Thomson. However, I see Burke and Smith connected with ruins in how all of these objects meditate on the construction of the self (either historically, physically, or emotionally), and the contemplation of its possible fragmentation. A text that I’d like to look more at for my prospectus that I think connects in usefully is C.F. Volney’s The Ruins, or A Survey of the Revolutions of Empires, translated into English in 1795.

Image Credit: Screenshot from Eighteenth-Century Collections Online

In this most interesting book, a first-person narrator is traveling through the East, meditating on the fallen empires, when he is accosted by the Genius or spirit of the ruins, who proceeds to give him the history of the ruined grounds upon which the narrator looks. Ruins here not only stand in for history, but also have the ability to speak and to interact with their observers. The sentimental tears of the narrator align him with a particular novelistic tradition of sympathy, like Smith, but this openness ends up shaking the foundations of his beliefs about empire. Here, the sentimental scene of a man looking upon ruins forces him into a violent confrontation with the object he sees, before which he is powerless. Being an eighteenth century self thus in these texts requires the self to always be open to being a ruin. The desire to construct aesthetic follies like Wimpole’s Folly, pictured at the top of the post, also speak to a desire for a constructable authenticity and relationship with the past. We want not just to know the past, but to be able to create it as well.

Hopefully in the future I’ll be able to add more speculations here about the visual rhetoric of eighteenth-century ruins. If you’ve enjoyed these speculations and want to read something further, I’d recommend Lynn Festa’s Sentimental Figures of Empire in Eighteenth-Century Britain and France and David Marshall’s The Figure of Theater: Shaftesbury, Defoe, Adam Smith, and George Eliot.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago