Image Credit: dc.wikia.com

In future posts I would like to delve into the ongoing conversation in the comic book world about the hypersexualization of the superhero women who fly, strut and kapow their way across the industry's glossy pages. Before reaching out to this debate in abstract terms, I would like to present one of the key images that catalyzed the explosion of feminist rage, feminist approval, and, quite frankly, some sexist reactionary defenses. In 2011, DC announced the New 52: a complete relaunch of their comic book line including, surprise, 52 titles all starting, or starting over, at issue #1. DC followers set the internet aflame with reactions, thoughts and feelings about the ensuing comics, and a particularly impressive inferno sprang up around Red Hood and the Outlaws #1. Why? Here's a hint. It's the reason this post is tagged Not Safe For Work.

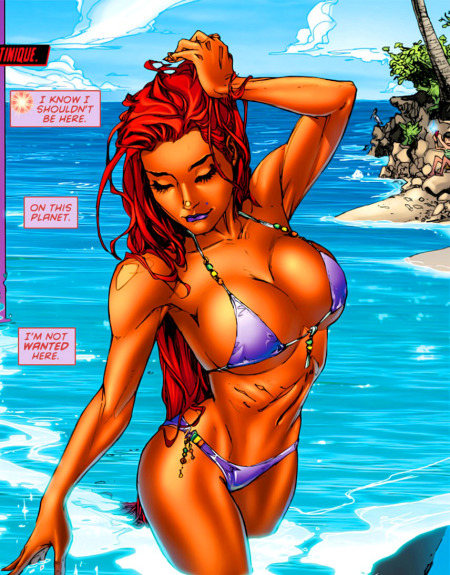

Starfire, a lesser-known DC character outside of the comic book subculture, features in this issue, gracefully splaying her body in suggestive poses and sporting one of those magical, physics-defying bikinis of the lift-and-separate class. A quick comparison with a Tales of the New Teen Titans cover from the 1980s provides a thorough story, told through visuals, about this character's meta-bildungsroman. Both Starfires are alien princess and on-again-off-again members of various superhero teams on earth, but the visual shifts that have accompanied Starfire's growth distinguish these two particular avatars. The 80s Starfire, though still scantily-clad, demonstrates some of the abilities that help define her as a superhero. She soars vertically through the air, her long, impressively buoyant hair leaving a flashing trail beneath her, marking her ascent. A beam of energy shoots towards the viewer from her outstretched hand. Sure, she sports a smile, an immaculate coiffure and a bikini, but we are encouraged to see her as active, exercising the abilities that make her super. The text beside her “REVEALED AT LAST! THE SHOCKING SECRET LIFE OF PRINCESS KORIAND'R!” becomes wryly amusing when juxtaposed with the 2011 Starfire. Revealed at last, indeed.

Image Credit: read/Rant

This Starfire's bikini has gotten even smaller, unlike the other prominent attribute of this frame. Admittedly, this outfit is not meant to serve the purpose of a uniform, but that's part of the point. This Starfire is showcased, not as a superhero, but as a hypersexualized pin-up girl. The vapor trail that signaled breakneck speed on the old cover has become a languid, sparkly trail of ripples in the water, marking the sensual path of her Venus-like emergence from the sea. Where the 80s Starfire crosses an arm over her chest to fire a ray at some unseen mark, the new princess's arms are pulled back and away from her torso, drawing attention to her breasts. The creators emphasize her desirability by including the ironic thought “I'm not wanted here” beside her bikini top in hot pink text.

The debate about unrealistically-portrayed superhero women includes the following questions: Are depictions of sexualized women, like that of the New 52 Starfire, inherently sexist in their objectification of the female form? Contrariwise, are they inherently feminist in their celebration of women's sexual liberation? Is there blame to go around for the convention of the supersexy heroine? Are comic book creators morally or ethically bound to make women's bodies more realistic? Or is the audience at fault? The industry itself? Are these images harmful to those consuming them or harmless fantasies of a cultural beauty standard?

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago