(Image Credit: Harry Ransom Center and J. Paul Getty Museum)

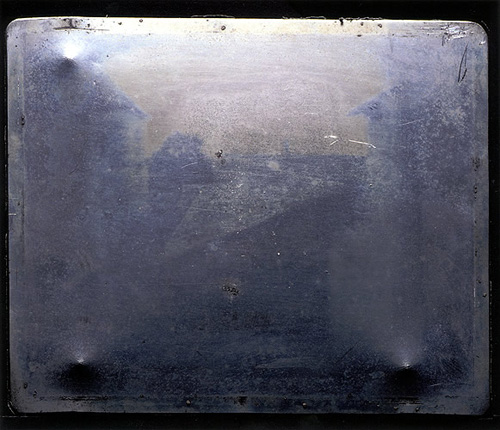

The first photograph is hard to see. Though, really, that shouldn't have come as a surprise. The Harry Ransom Center makes it exceedingly clear on their website that not only will the image be difficult to make out, but that each viewer will in some sense be reperforming its discovery. Their instructions for viewing the photo include a short epigraph by Helmut Gernsheim, a photohistorian that rediscovered the piece in 1952. Of his first viewing of the photograph he writes "No image was to be seen. Then I increased the angle—and suddenly the entire courtyard scene unfolded itself in front of my eyes. The ladies were speechless. Was I practicing black magic on them?"

(Image Credit: Harry Ransom Center)

My encounter was the opposite in some regards. The Ransom Center was hosting a local field trip when I went to take a second look at Joseph Nicéphore Niépce's photograph (my first look at the piece was little more than a quick glance during a hurried round through the collection), and there were two girls sitting in the photo's viewing room diligently working on some field trip assignment that involved drawing multiple versions of the photograph. I stood square in front of the piece, looking down at it through the several plates of glass, tilting my head this way as I attempted to shift the glare somewhere less bothersome. They stood less for my unseeing than I did, and I was quickly instructed by a helpful, if somewhat exasperated, voice behind me to look at it from different angles. I obliged.

(Image Credit: Harry Ransom Center)

I wasn't, though, magically greeted with something like the reproduction. Instead, as I twisted around the piece as best I could, I was given only the slightest hints of the image that the pewter plate had captured. Having seen the clearly defined reproduction I could, to a degree, reinscribe it upon the object that I was viewing, but the more that I changed my perspective the more that began to get the sense that it was resisting that simple reinscription. It refused my simple attempts at situating it as a simple representational image. I could only ever take in a portion at a time; the image was fleeting as it moved counter to inescapable glare and the difficulty of its physical properties.

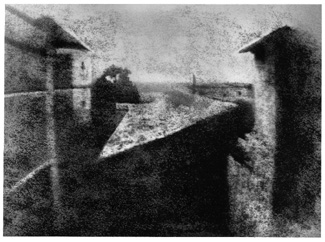

It wasn't just the glare and polished pewter that disturbed any fully formed viewing. The image I was hunting for is, itself, impossible. Due to the incredibly long exposure time required to capture an image it presents an eccentric space. The first permanent photograph of nature is unnatural; rather than presenting a moment it contains a day long duration with the confused shadows to match. It asks the viewer to view it as it views the world—slowly.

Any attempt at taking this object as merely representational image, though, is sure to be frustrated. The intended viewer, before even laying eyes on the pewter plate, is thoroughly situated by the exhibit. You can hardly make it to the object itself without seeing an image of the reproduction. And the reproduction, rather than an image of the pewter plate is itself an imagining of what the photograph could have captured. So that while the reproduction shows us what the plate perhaps saw what we see is not a representation of nature. The first photograph doesn't represent anything; it doesn't point toward some point in space and time. Instead what I saw was an object viewing the world. It, as it sits framed and under glass, invites the viewer to share with it a particular way of seeing.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago