Site informationRecent Blog Posts

Blog Roll

|

Google Earth Pedagogies: Making the Most of Map Databases

Submitted by Laura T. Smith on Mon, 2010-03-08 14:10

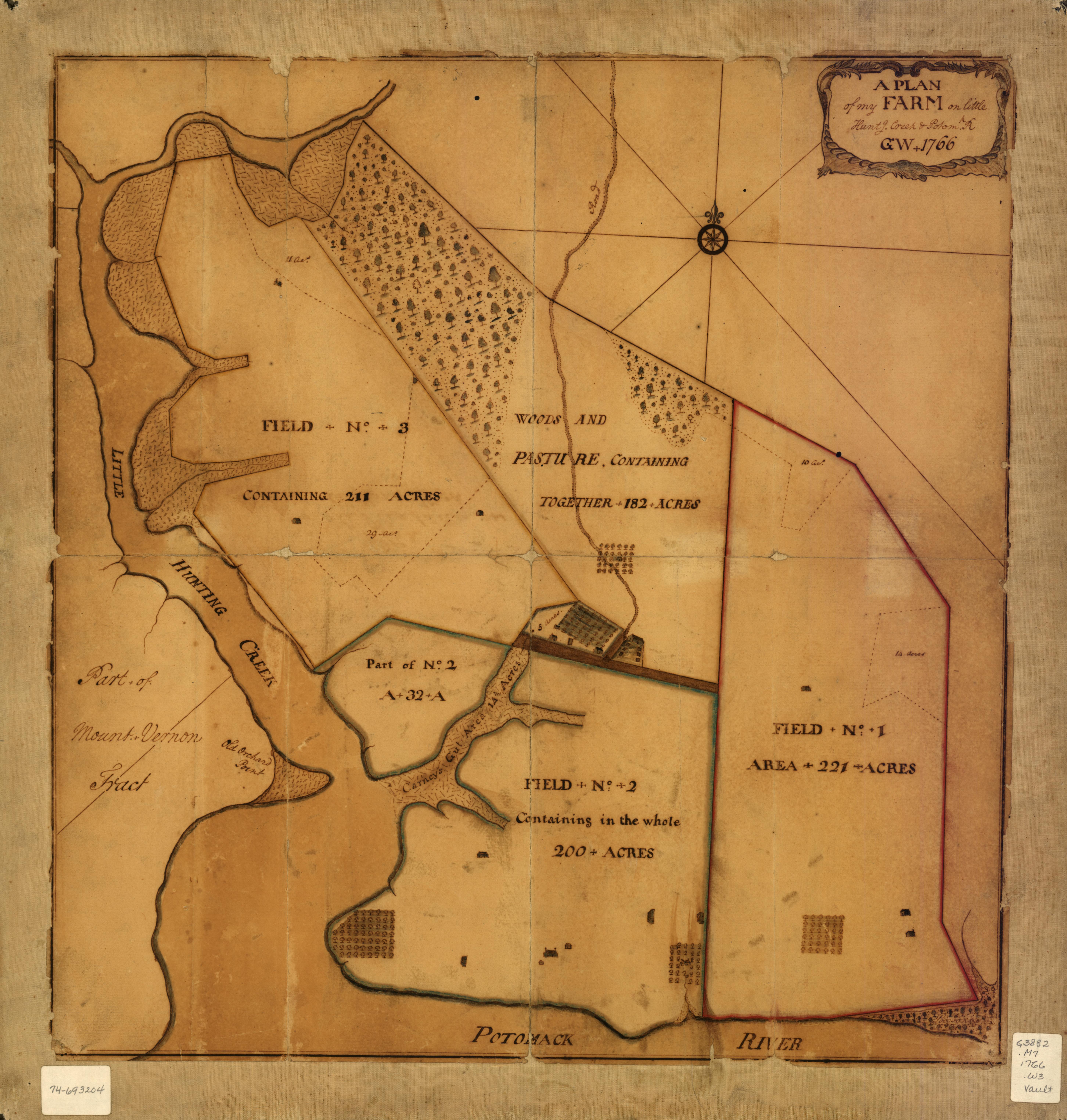

(Image source: Library of Congress Map Collections) The above map, created by George Washington in 1766, depicts “A plan of my farm on Little Huntg. Creek & Potomk.” This map, which is publicly viewable at the Library of Congress Map Collections and downloadable as a high-resolution JPEG2000 file, is included in the Collections’ “Cultural Landscapes” section, which highlights the ongoing cultural construction of United States and World landscapes through the ways individuals, communities, and nations modify land. This subsection of the online Collection places an array of cartographic materials into conversation: a set of local maps authored by George Washington, a series of maps of Liberia created by the American Colonization Society, and a store of historical U.S. atlases. One of the distinguishing features of The Library of Congress’s Map Collection is that it is part database, part exhibit. The online Collection boasts sophisticated cataloguing and imaging standards, allowing users to zoom in on maps, examine details, download high-resolution image files, and refer to helpful notes about the map’s physical features and provenance, including scale, media, size, accompanying materials, and source. The site also offers helpful advice about copyright, noting that materials in the collection are generally not copyrighted materials; the maps “were either published prior to 1922, produced by the United States government, or both.” The site clearly aims to make the Library’s cartographic collections freely available and digitally accessible and to encourage users to download and use these materials for study, education, research, and enjoyment. The site intersects at many points with the Library’s larger “American Memory” project, which has digitized over five million items from the Library’s Collections since 1996. I am interested in the possibilities of a maps database such as the Library of Congress Map Collections partly because of the prospect of using historical maps within Google Earth, and partly because our Visual Rhetoric workgroup is preparing to host an upcoming workshop, “Best Practices for Digital Images” on Friday March 26th at 1 pm. One component of the workshop will be an introduction to the many rich image databases that are available on the web. To that end, some of our posts over the next few weeks will serve to review and evaluate some of these databases. Three significant, online map databases are The Library of Congress Map Collections, the Perry-Castanada Map Collection at the University of Texas Libraries, and the David Rumsey Map Collection. These collections all have large holdings that are available to the public and offer downloadable images, though only the Library of Congress and the David Rumsey Collection offer consistently high-resolution downloads. (The Perry-Castanada Map Collection seems to prioritize keeping files to a manageable size for its users; the website claims that most of its images, usually JPEGS or PDFs, are kept to size standards of 200K to 300K.) These three collections, run by a federal organization, a public university, and a private company, respectively, vary widely in terms of cataloguing and indexing practices, image quality, image context, and general online experience. My aim today will be to offer a very brief overview of the first two image collections, Library of Congress Map Collections and the Perry-Castanada Map Collection. (I'll discuss the Rumsey Collection in a later post.) I will give an expanded analysis of the features and utility of Library of Congress’s Collection for pedagogical applications. The Library of Congress Map Collections, the online arm of the Library of Congress’s Geography and Map Division, represents a small fraction of the holdings of the Map Division’s collection, which includes more than 4.5 million items. The Library of Congress Map Collections began as a massive digitizing project in 1995. The Library does not estimate how many maps are online, but notes that new materials are digitized and added continually. The Perry-Castanada Map Collection includes more than 250,000 maps, 11,000 of which are available for online viewing. (In addition, maps from the Perry-Castanada Map Collection can also be physically checked out by students, faculty, or the general public for a two-week borrowing period.) As I noted above, the Perry-Castanada Collection does not prioritize providing high-resolution images or downloads of their materials; their files, generally formatted as JPEGs, GIFs, or PDFs, are considerably smaller than those of the other two sites. The Perry-Castanada Collection does offer categorized links to hundreds of other map collections though, including the Library of Congress and The Rumsey Collection, as well as other research collections and independent web sites. While each digitized map is indexed in the Library’s general catalogue, the Maps Collection does not include the catalogue information or a link to the catalogue entries, so, in fact, the amount of information about the map available with the image is minimal, usually including the title of the map or atlas in which it was printed, its publication date, and sometimes the organization that published or produced it. The user has to separately look up the map in the online catalogue to obtain full information. The full catalogue entries offer additional information such as the map’s author, but the general purpose catalogue does not give the depth of information one might expect from a special collections catalogue entry, including detailed notes about medium, size, inscriptions, accompany materials, or provenance. As I noted earlier, the Library of Congress Map Collection works like a database and an online exhibit at once. The materials are indexed via a number of different methods: the whole collections is divided into seven major thematic categories, which allow users topical entry into the cartographic resources. Those categories include

Nearly every collection includes a “Special Presentation,” an online exhibition with text and images that invites users to delve into some selected resources within the collection, rather than using the site by entering specific search terms. This feature allows users to have a curated, museum experience, clearly serving not only the Library’s goal of making documents available to the public, but also its educational goals. While users can browse within these thematic categories, which include their own Collection Guides, users can also search by keyword, or browse indexes by geographic location, subject, map creator, or map title. Indeed, as the above list of browse-able indexes suggests, the site relies heavily on browsing to make its resources available to users. For example, as the visitor enters the Railroad Maps Collection, she finds only a very cursory introduction to the collection—a total of five lines of text—on its home page, and this Collection happens to include no curated “Special Presentation” to introduce the user to the Collection’s material, so searching or browsing become her best methods of accessing information. Fortunately, the Geographic Location Index offers a robust, visual, clickable map icons to help users locate materials by country (Canada, United States, Mexico, and West Indies), U.S. region, and U.S. state. In this way, the Library of Congress Map Collections site combines sophisticated cataloguing methods with an inviting, browse-able online environment. The icons that accompany the seven thematic categories perhaps best express this mission of the site: each is a collage of multiple materials from the category, with numbers identifying the source of each element of the collage, which are clickable:

(Image source: Library of Congress Map Collections) The Cultural Landscapes icon, for example, pairs a detail from the 1766 Washington map (pictured in full at top) with a detail from an 1867 American Colonization Society map, “St. Pauls River, Liberia at its mouth.” The clickable collage, which links to each element's catalogue page, represents the site’s values: user-based discovery (facilitated by either browsing or searching), curated experience, thematic intersections, accessibility, and high-quality image and cataloguing standards. By clicking on the category icon, the user not only enters the "Cultural Landscapes" section, but is confronted by provocatively juxtaposed visuals accompanied by links to each detailed source page. Not surprisingly, the site offers extensive materials for teachers, including classroom ideas, lesson plans, and primary source sets (groups of images related to a historical period or theme) through its “Collection Connections” section. The Collection’s choice of somewhat unusual file formats for images is, perhaps, an unfortunate extension of the value placed, at once, on accessibility and high quality that I appreciate throughout most of the site. Rather than offering more common image file formats such as TIFFs GIFS, or JPEGS, the Library has chosen to compress their large documents as JPEG2000 and MrSID files to preserve detail and enable high-resolution downloads. Both of these formats require plug-ins, and while the site offers links to free versions, I would have liked to have available a low-resolution option (a GIF or JPEG) that required no software plug-in. Tags:

|

viz.

Visual Rhetoric - Visual Culture - Pedagogy

Site informationRecent Blog Posts

|

Google Earth Pedagogies: Making the Most of Map Databases |

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago