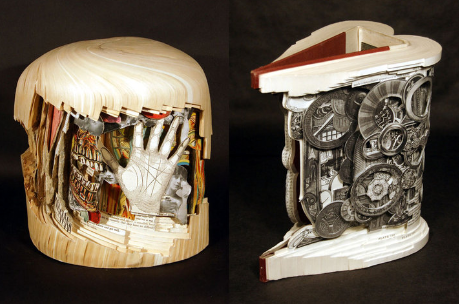

Libraries of Health and Complete Antique, Brian Dettmer.

H/T to Brian Gatten, Lauren Gantz and NPR

In honor of World Book Day (March 3--but it's not too late to celebrate!) NPR's visual culture blog, The Picture Show, featured work by Atlanta artist Brian Dettmer. Dettmer takes vintage books and carves them into sculptures that, as Mito Habe-Evans explains, "[deconstruct] the linear narrative determined by the structure of the book" and open the door for new interpretations. In giving new life to a supposedly dying medium, Dettmer's sculptures make an argument about the cultural space of physical books, now and in the future.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago