Strong is the New Skinny, OR: Why I Hate the Strong Female Character

This post started with a t-shirt. It draped across the shoulders of a college student—female, attractive—and sported the slogan “Strong is the New Sexy.” The shirt caught my attention because it was neon orange, but the slogan stuck. It seemed both snappy and dense, culturally relevant and straightforward.

Image Credit: Jenniver Cohen and Stacey Colino, Amazon.com

Since this first incident, I have seen variations of the slogan plastered on other fitness gear, in exercise guides, and in academic material. “Strong is the new skinny,” “Fit is the new young,” and so on. Just do a Google Image search, and you’ll get hundreds of variations, complete with stunning and talented female bodies:

Image Credit: Google Images

I can see why these assertions are attractive. Initially striking, they seem to reject widespread negative body ideals that require thinness, self-objectification, and passivity. Strong is the new sexy. It sets up “sexy” as an outdated ideal, as something to be replaced. Further, it casts the wearer (speaker, writer) as a cultural progressive, someone insistent on reclaiming femininity—because the slogans, after all, imply femininity. Whatever the adjective—sexy, skinny, young—the implicit understanding of the slogan is that females in particular have felt pressured to strive for it. Replacing these ideals with “strength” seems a step in the feminist direction, and a particularly important step for teenage girls, long understood both colloquially and academically to struggle with body image.

Despite my initial enthusiasm, however, the sticky slogan soured in my mind, coming to represent a dangerous double-narrative. I realized the slogan also implied that striving for strength is a fad, another temporary trend in ideals. In addition, this indication of impermanence echoes the patriarchal lionization of female youth and young female bodies that troubles feminism. More importantly, though, the motto narrows positive femininity to strong femininity, a connection many of us in politics and academia take for granted. It might be more productive, though, to question that link, particularly because this fitness discourse has become literary, in the form of the Strong Female Character as a role-model for adolescent girls. Because “strength” both limits young female fortitude to the physical realm and is continuously used as a panegyric, catch-all term for other, more specific positive attributes that feminists encourage in their younger counterparts, it not only masks the nuances of youthful femininity, but also comes to represent yet another masculine standard to which they are expected to conform.

I keep emphasizing adolescent femininity because it seems to me that this discourse of strength is often tacked on to lazy literary studies’ version of the Strong Female Character. I’m thinking, specifically, of the proliferation of popular books that feature these mythical SFCs. Here’s one:

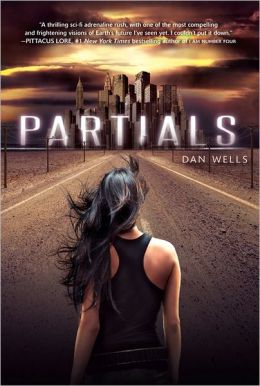

Image Credit: Dan Wells, Barnes and Noble

Here we get the back of a teenage girl, no bra lines, killer shoulder definition, and (of course) luscious hair. She’s staring at that city as though she’ll take it down, and the space around her slim figure suggests she’s isolated both physically and emotionally from a source of support. The implication here is that she is strong because she is physically capable of taking off at a nice clip down that road, and that she should be expected to do so alone.

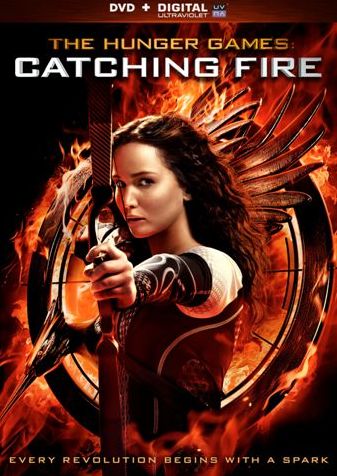

I did a very brief search through some contemporary Young Adult book covers. Some of them feature symbols (like the original Hunger Games series) or clothing (like the Pretty Little Liars books), but a large subset of them depict a female figure in this vein. Unsurprisingly, these covers are also the ones whose readers throw around the Strong Female Character slang. Almost all of them, like Partials, advertise their books with a striking visual image of a girl, usually alone, often surrounded by dangerous conditions, exhibiting physical strength in some way. The Great Jennifer Lawrence, star of The Hunger Games: Catching Fire, has come to represent Katniss on book covers, too:

Image Credit: Suzanne Collins, Barnes and Noble

While this label of the Strong Female Character has long been popular, it has, lately, risen even further to the cultural forefront, particularly through the vehicles of literary-turned-cinematic phenomena like the Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight or Suzanne Collins’s The Hunger Games franchises. Yet the texts to which it has been applied are varied and nuanced, often packaging either postfeminist consumerism or a blanket disavowal of “soft” femininity as "feminism." For example, Twilight’s Bella Swan has been both denounced as “so anti-feminist I want to cry” and praised as a “postfeminist agent” (Summers 315, Moruzi 61). The vacillation in opinion regarding Bella reflects how vague the term “Strong Female Character” truly is. Similarly, Katniss Everdeen, first-person protagonist of The Hunger Games has come to represent, in both journalistic and academic discourses, the paradigmatic Strong Female Character of the last five years. Yet, when interviewed about Katniss’s performance of gender, girls responded: “She acts like a, a boy,” “I think she’s more like a guy,” “I think um, she’s strong and you better not get in her way or something ... Sometimes I think she’s a boy in the scenes” (Taber, et. al 10-11). This latter respondent herself made the link between Katniss’s performance of masculinity and the multifaceted physical, emotional, and mental strength we expect from Strong Female Characters: “she doesn’t cry and stuff so that probably makes her strong” (11). While Bella’s strength is a hot topic for debate, why does Katniss’s go virtually unquestioned?

Just as “Strong is the new sexy” presumes a connection between external and internal characteristics, many of these Strong Female Characters are presented as muscular, skilled with weapons, or supernatural. In recent years, we have seen a proliferation of female characters whose strength is defined by their muscular physiques, proficiency in combat, or emotional isolation. We have seen Lara Croft, Sydney Bristow, and Buffy Summers on film and television. Visual representations of these females give us isolated women, often facing away from us, tormented by the elements and a cruel or broken society:

Image Credit: Veronia Roth, Goodreads

Throughout the discourse surrounding these characters, the image we get of the Strong Female character is associated with several buzzwords, most notably “independent,” “self-sufficient,” “assertive,” “intelligent,” and “courageous.” What I would like to emphasize, then, is the way that these visual depictions of external, muscular strength are meant to represent those internal qualities, fusing them together to that the characters designated “strong” are also expected to obtain many, if not all of these other modifiers. For example, another recent young adult heroine, Elisa of Rae Carson’s Girl of Fire and Thorns, grows into her role as ruler of a kingdom over the course of her novel. Carson’s Elisa is a dynamic girl, an overweight leader who combines multiple traits of greed, lust, leadership, focus, and intelligence. Her book cover shows us, instead of the full-body tank-top shot, simply a face:

Image Credit: Rae Carson, Goodreads

On social reading site Goodreads, many reviewers praise Carson for creating one of the most unique Strong Female Characters in recent years. Yet many others refused Elisa this label because she is overweight, claiming that her physical size made her lazy or stupid—even this book cover minimizes the role of Elisa’s weight in the novel (which is huge for theme), placing her inside a tiny precious jewel instead. Despite moral character and intellect, then, her “strength” still depends on her skill with weaponry and her muscular definition. While the term “Strong Female Character” has been unquestioningly adopted and widely applied to physically strong females, I have found no equivalent modifier for a girl character who possesses other positive attributes. The Brainy Female Character and the Artistic Female Character, it would seem, either do not exist (obviously untrue) or remain nameless.

More importantly, the adjectives implied under the “strong” umbrella, especially “independent” and “assertive,” are specifically postfeminist in that they echo the values of neoliberalism. That is, in order to be “strong,” the young female must conform to capitalist values. It is this valorization of competence, assertiveness, and independence that lead to Barbara Hudson’s assertion that adolescence and femininity subvert each other, because the primary values of adolescence conflict with the experience of adolescent femininity, in which girls are taught to make themselves small, to withdraw, and to emphasize interiority. To glorify independence in females, then, is in part a step away from this contradiction, a validation of girls who do not follow the prescriptive of docile femininity. On the other hand, it implies that the neoliberal values of aggression and self-sufficiency are the appropriate rubric against which to measure teenage girls. As Rosalind Gill writes in her analysis of postfeminist media culture, “[w]hat is striking is the degree of fit between the autonomous postfeminist subject and the psychological subject demanded by neoliberalism” (154). This subject is not simply the product of neoliberal ideals, but also of masculinism. To uphold that “strength” must be associated with independence and assertiveness also affirms a purely Western way of viewing the world, in which weakness is punished by feminization, and shame and strength is upheld as the public goal.

Again, I do not mean to suggest that independence, self-assertion, or strength are solely the purview of males, or that these attributes should not be encouraged in girls. Rather, it is the vagueness with which they are (not) defined that becomes troublesome. By allowing “strength” to stand in for any positive attribute, we become complicit in a cultural agenda that marginalizes the communal, the vulnerable, the soft. There is nothing soft about these covers or, we are asked to believe, their contents.

Image Credit, Veronica Rossi, Barnes and Noble

The discourse of the Strong Female Character seems, to me, to have found a home in the idea that strong is the new sexy, the new ideal—but how are we defining “strength”? Is it through skill with the bow-and-arrow? Stubbornness? A bad attitude? Further, are there differences in the kinds of characters older feminists view as strong and those that girls themselves find empowering? I realize that questioning the strength ideal, like the ideal itself, leads to uncomfortable territory. “Strength” has such a positive connotation that to test its limits feels unnatural, even anti-feminist. My hope, in looking at these images, is not to discourage strength for girls; instead, I hope use my discomfort with the strength ideal exhibited in these discourses to call for a new, more nuanced vision of adolescent femininity. In this case, girl feminism and the Strong Female Character, like muscle tone, need definition.

Works Consulted

Alias. Creator, J.J. Abrams. Perf. Jennifer Garner, Ron Rifkin. ABC, 2001-2006. Television series.

Ali, Nyala. “From Riot Grrrl to Girls Rock Camp: Gendered Spaces, Musicianship and the Culture of Girl Making.” Networking Knowledge 5.1 (2012): 141–160. Print.

Bordo, Susan R. Unbearable Weight: Feminism, Western Culture, and the Body. University of California Press, 2003. Print.

Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Creator, Joss Whedon. Perf. Sarah Michelle Gellar. Fox, 1997-2003. Television Series.

Carson, Rae. The Girl of Fire and Thorns. HarperCollins, 2011. Print.

Collins, Suzanne. The Hunger Games. USA: Scholastic Inc., 2009. Print.

Gill, Rosalind. “Postfeminist Media Culture: Elements of a Sensibility.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 10.2 (2007): 147–166. Print.

“The Girl of Fire and Thorns (Fire and Thorns, #1). Reviews” Goodreads. Web. 4 May 2013.

Inness, Sherrie A. Tough Girls: Women Warriors and Wonder Women in Popular Culture. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999. Print. Feminist Cultural Studies, the Media, and Political Culture.

Jackson, Sue, and Westrupp, Elizabeth. “Sex, Postfeminist Popualr Culture and the Pre-Teen Girl.” Sexualities 13.3 (2010): 357–376. Print.

Kane, Jennifer. “Can Strong Really Be the New Skinny?” Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance 83.6 (2012): 6–12. Print.

Lara Croft: Tomb Raider. Dir. Simon West. Perf. Angelina Jolie. Paramount, 2001. Film.

Meyer, Stephenie. Twilight. Little Brown, 2008. Print.

Pipher, Mary. Reviving Ophelia: Saving the Selves of Adolescent Girls. 1st ed. Riverhead Trade, 2005. Print.

Roth, Veronica. Divergent. HarperCollins, 2011. Print.

Tasker, Yvonne. Spectacular Bodies: Gender, Genre and the Action Cinema. Routledge, 1993. Print.

Tasker, Yvonne, and Diane Negra. Interrogating Postfeminism Gender and the Politics of Popular Culture. Durham, [N.C.]: Duke University Press, 2007. catalog.lib.utexas.edu Library Catalog. Web. 17 Apr. 2013. Console-ing Passions.

Add new comment