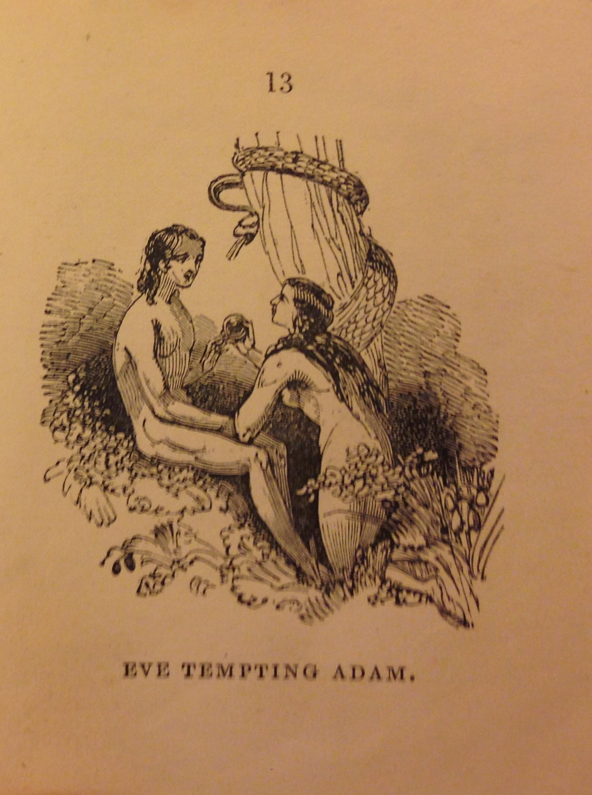

The Serpent Was a Creeper: Religious Representations of Animals and Humanity in Children's Literature

Image Credit: The Little Picture Bible, by Isabella Child

When I was a child, I liked to imagine Adam in the Garden of Eden, surrounded by docile beasts as he handed out names like candy. "Elephant," he'd say--and I liked wondering whether Elephant was a proper noun, the name “Elephant," or simply a category. Elephant would smile gratefully and lumber to the back of the group so that Adam could see and name his next subject.

In my child's mind, Adam spoke English. It would not have occurred to me than my mythic ancestor would perhaps not be white and would perhaps not speak with the Standard English Grammar I was learning in school. Still, the names of the animals didn't matter so much; feline, avian, and primate were irrelevant in the face of that iconic act, the ceremony of naming that gave Man authority over the animals.

I wonder if Adam also named Eve.

I revisited my child's imagination of this event last year as I worked on a research project featuring about two dozen children's Bibles. During the mid-to-late nineteenth century, cheaper illustration techniques and mass production allowed illustrated Biblical storybooks to virtually flood the markets in both Britain and America. What surprises me, looking back on these images of elementary faith, is the prevalence of animals in these tales. They seem to show up primarily in one of two ways—first as a group of subjects waiting for names and secondly as a single serpent luring the couple’s attention away from God. Animals in these children’s Bibles are serving two important functions, then: firstly, they solidify humankind’s dominion, and secondly they signal humankind’s separation from the deity. I’m interested, particularly, because it is this connection with animals that makes so many religious literalists uncomfortable: if we are descended from animals, how can we be made in God's image? What would they say, I wonder, to the not-quite-human Adam and Eve in this Bible:

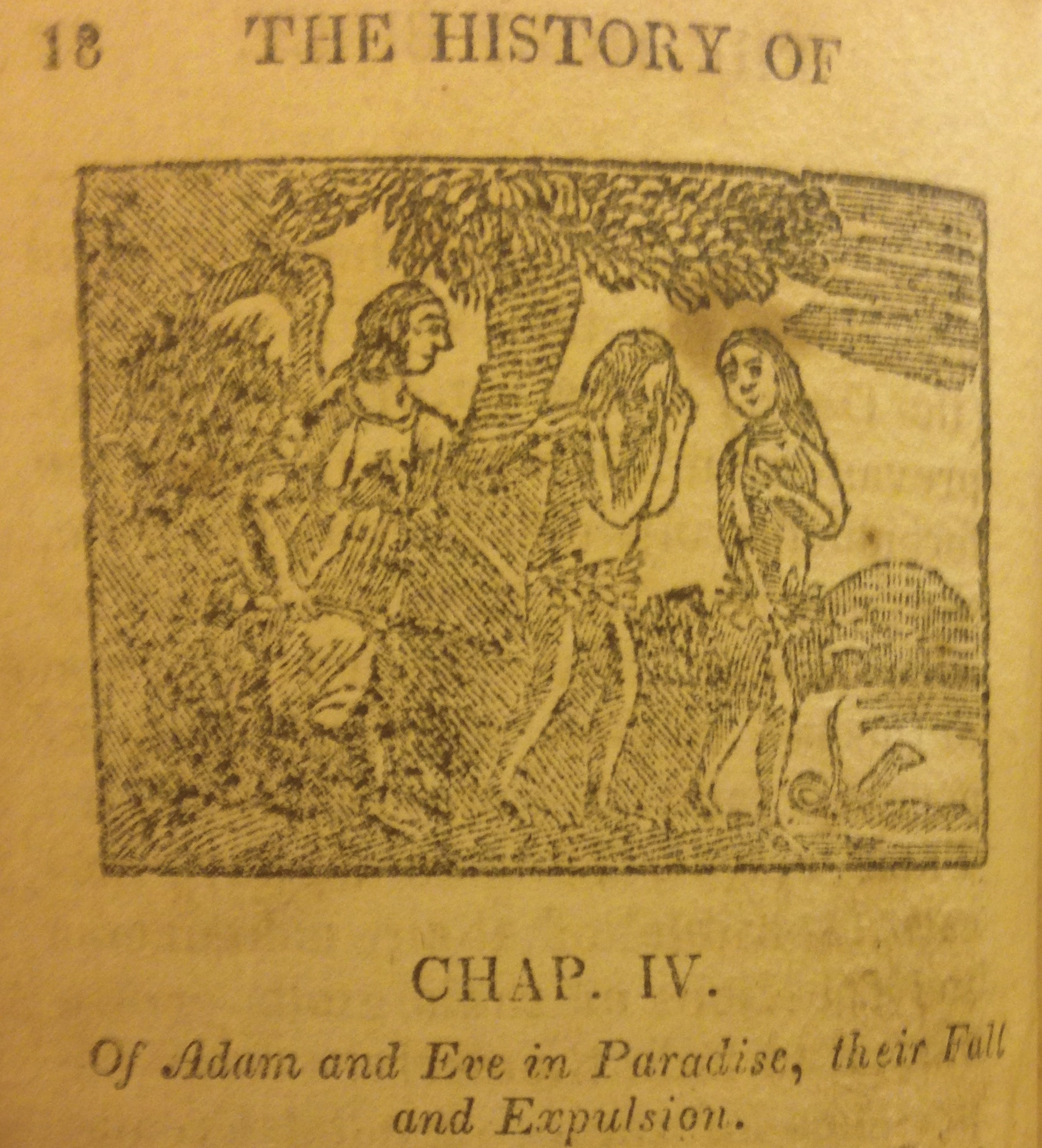

Image Credit: The Holy Bible Abridged, or, the History of the Old and New Testament: For the Use of Children, by Thomas Carey

Of course, I'm not claiming that the unknown illustrator of this little book meant to underscore the simian cast to Adam and Eve. Quite the contrary: although, as scholars of science and Victorian literature like George Levine have pointed out, the relationship between religion and evolution was not nearly so adversarial as we might assume, I do suspect that the producers of this Bible would be uncomfortable with how frankly evolutionary this image looks. Most likely, the figures are drawn this way because illustrative technology did not allow for much detail, and because this book, Thomas Carey’s The Holy Bible Abridged or The History of the Old and New Testament for the Use of Children (1820), measures less than two inches by four.

Almost all of these Bibles, though, features some kind of Adam-Eve-Animals illustration. A few do show Adam naming the animals, although this scene is far more common in contemporary children's Bibles like this one, from Kelley Pulley’s The Beginner’s Bible:

Image Credit: Google Books The Beginner's Bible, by Kelly Pulley

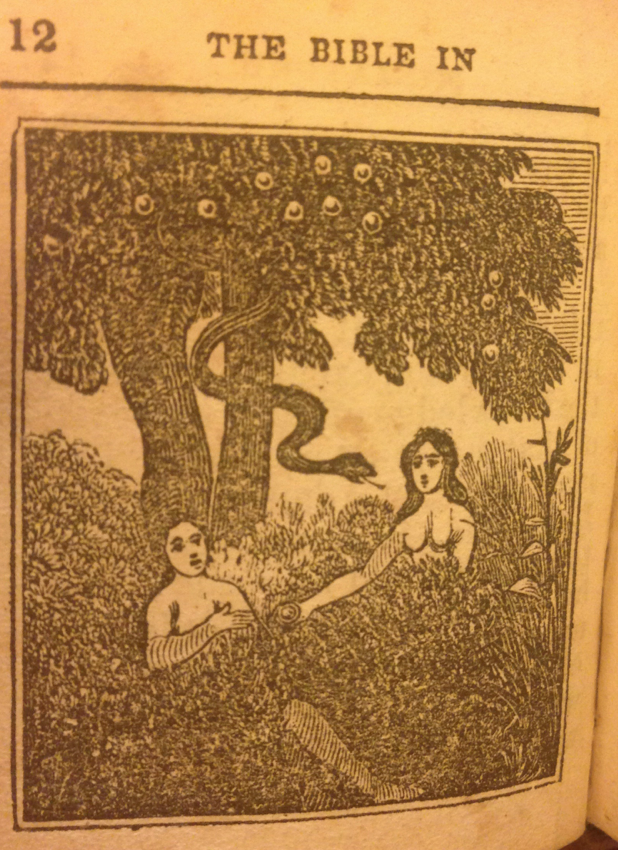

Nearly every Bible, though, gives us some kind of Adam-Eve-Serpent depiction. For example, The Bible in Miniature for Children (1835) features a topless Eve and a passively reclined Adam:

Image Credit: The Bible in Miniature for Children

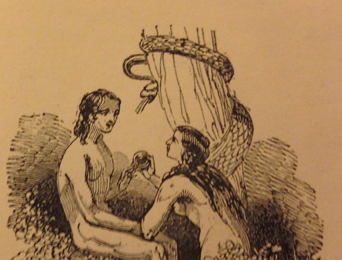

My favorite, though, is Isabella Child’s Little Picture Bible, published in 1835 and sold in a collection alongside other little books such as British Quadrupeds and British Birds:

Image Credit: The Little Picture Bible, by Isabella Child

These two images above were published in Bibles the same year. Child’s was more expensive, of course, and framed as a collector’s item. Still, this last image is striking (Look at Adam’s thigh muscles!) especially because the snake looks like such a voyeur.

To state the obvious: how we position animals in illustration says a lot about the way we want our offspring to consider themselves in relation to other life forms. In the images above, Adam and Eve are the stars—and this trend continues through most contemporary children’s Bibles. They, along with other Biblical figures (usually old white males) take up central space in nearly every illustration in the Bibles I've surveyed. Here, the serpent (retrospectively named Satan in a culture-wide collation of all evil figures into a single archenemy) observes what could be the beginning of a sex act. I was surprised by how explicit this image is. Take away the strategically-placed elbow and leafy branch, and we get something dangerously like an erotic illustration. Why is the snake so interested? Where is his eye line actually going?

In these and other illustrations, animals are positioned as observers or as subjects. Here, the serpent is upsetting the natural order simply by interacting with the couple. The snake hisses encouragement at Adam (who does not seem to be concerned with the fruit) while his body seems to disappear into Eve's. In The Bible in Miniature, the serpent seems to be whispering to Eve, not unlike a totem or spirit animal. In each case—and this is a trend in most nineteenth-century children’s Bibles, the animals appear in illustration to enhance, to witness, or to enjoy the humanness of Adam and Eve.

In 1923, Hendrik Willem van Loon, who, incidentally, won the first Newbery Medal for his anthropological children’s book The Story of Mankind (1921), followed up his success with The Story of the Bible. Van Loon’s was one of the first “Biblical” texts to acknowledge alternative world views, framing the Creation Story as a depiction of what Jews and Christians believe. Flipping through my own copy, I’m surprised to note that not only are animals almost absent from the illustrations, but people, too, are minimized—as if Van Loon diminished the entire animal kingdom by suggesting that humans may not be made in God’s image. Instead, almost all of Van Loon’s illustrations feature architecture or landscape. In shifting focus away from the Grand Narrative of Judeo-Christian creationism, Van Loon seems also to have shifted focus away from humanism.

This makes me wonder about the visual representation of animals and humanity in a religious and secular context. A series of other genres explore this relationship. Rudyard Kipling’s Just-So Stories, for example, follows a pseudo-folktake tradition of explaining animal characteristics through narrative (this text has also been skillfully illustrated by multiple artists). Within the next couple of months, too, we can anticipate the publication of Great Adaptations, a series of evolutionary children’s books by evolutionary biologist Tiffany Taylor. Dr. Taylor, already a children’s book author, has gotten her project funded (actually she has doubled her goal in donations) through Kickstarter. The books, which contain the work of multiple illustrators, will pair verse with illustration to explain evolutionary concepts.

Of course, the depiction of animal-child or animal-human relations is not unique to religious or scientific illustrated literature. Still, as the primary genre for illustration and for epistemological instruction, children’s literature is a privileged place for looking at how we teach animal ethics. Sure, I can poke fun at the snake’s role in this unusually intimate (for a nineteenth-century children’s religious text) scene. More than that, though, these illustrations and the upcoming ones to be found in Great Adaptations seem to crystallize the epistemological issues of animal ethics, scientific method, and spiritual experience. They communicate answers to big questions about ecology, food chains, and human domination. Or, at the very least, these images suggest the place of animals in a human-dominated world and make us wonder what the hell that snake is looking at.

Works Referenced:

The Bible in Miniature. Worcester: Dorr, Howland, c1835. Print.

Carey, Thomas. The Holy Bible Abridged, or, the History of the Old and New Testament: For the Use of Children. Salem: Thomas Carey, 1820. Print.

Child, Isabella. The Little Picture Bible. London: C. Tilt, 1835. Print.

Kipling, Rudyard. Just-So Stories. New York: Viking Kestrel, 1987. Print.

Pulley, Kelly. The Beginner’s Bible: Timeless Children’s Stories. Grand Rapids: Zonderkidz, 2005. Web. 2 Sept 2014.

Van Loon, Hendrik Willem. The Story of the Bible. New York: Boni & Liveright, 1923. Print.

Add new comment