By Lauren Mitchell

Surveillance is not what first comes to mind when you think of visual rhetoric. Although images collected via the various forms of surveillance are often perceived as irrefutable evidence and therefore not rhetorical, surveillance images, like photographs, are as rhetorical as any other piece of evidence. There are several controversies surrounding use of surveillance both by public and private agencies that are relevant to visual rhetoric. These controversies include how surveillance can redefine a space, can create a power disparity between observer and observed, and is dependent upon interpretations that may be biased. Since the technological capabilities of the surveillance industry have exploded in the last decade as have the instances their use, it is important to consider the rhetorical implications of these forms of evidence.

Surveillance is not what first comes to mind when you think of visual rhetoric. Although images collected via the various forms of surveillance are often perceived as irrefutable evidence and therefore not rhetorical, surveillance images, like photographs, are as rhetorical as any other piece of evidence. There are several controversies surrounding use of surveillance both by public and private agencies that are relevant to visual rhetoric. These controversies include how surveillance can redefine a space, can create a power disparity between observer and observed, and is dependent upon interpretations that may be biased. Since the technological capabilities of the surveillance industry have exploded in the last decade as have the instances their use, it is important to consider the rhetorical implications of these forms of evidence.

CCTV and surveillance cameras are now commonplace in the U.S. and even moreso in Europe. Although these cameras are a boon for law enforcement for crime-solving purposes, they do not come without complications. Some studies have shown that surveillance cameras only move crimes to different areas and only prevent property crimes, not violent crimes. In this sense, surveillance cameras simply redefine a particular space as inappropriate for certain activities (Koskela 5, Doctorow) The cameras themselves can redefine spaces in other ways too. For example, some critics argue that people feel anxiety about being watched, and may also feel anxiety about why the space needs to be monitored. (Koskela 5) In addition, the cameras can also create an unequal power relationship—those observing hold all the power, while those observed are powerless. This seeps into gender issues as evidenced by several court cases about men using surveillance cameras to watch women. Essentially, these cameras have the power to redefine both the spaces and the people that they watch. They can make arguments about what roles both people and places are supposed to fulfill.

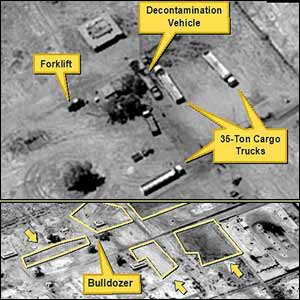

Satellite imagery illustrates the problem of interpretation that lies at the core of surveillance. Satellite images, as well as surveillance camera images, are considered to be factual and this is why they are such powerful forms of evidence. However, it is not the images themselves but the interpretations of the images that serve as evidence of an argument. In this way surveillance images can be deeply rhetorical despite their empirical reputation. This issue of interpretation also applies to another form of surveillance, biometrics. Studies have found that human biases inevitably seep into interpretations of Facial Recognition Software in ways that are similar to how satellite images and surveillance camera images are often simply interpreted to confirm pre-existing assumptions. The most famous example of the rhetoricality of surveillance is exhibited in the Bush Administration’s interpretations of satellite images of Iraq’s alleged chemical weapons facilities. (Kreuter)

Satellite imagery illustrates the problem of interpretation that lies at the core of surveillance. Satellite images, as well as surveillance camera images, are considered to be factual and this is why they are such powerful forms of evidence. However, it is not the images themselves but the interpretations of the images that serve as evidence of an argument. In this way surveillance images can be deeply rhetorical despite their empirical reputation. This issue of interpretation also applies to another form of surveillance, biometrics. Studies have found that human biases inevitably seep into interpretations of Facial Recognition Software in ways that are similar to how satellite images and surveillance camera images are often simply interpreted to confirm pre-existing assumptions. The most famous example of the rhetoricality of surveillance is exhibited in the Bush Administration’s interpretations of satellite images of Iraq’s alleged chemical weapons facilities. (Kreuter)

However, some see the possibility of positive outcomes from the universality of surveillance technology. Google Earth, along with webcams and private surveillance cameras, provide a way for the public to “look back” at governmental or corporate agencies. Many critics tout them as a way for the power of surveillance to be spread more evenly throughout society. Through these technologies everyone is in Foucault’s panopticon; everyone is both observer and observed.

Works Cited and Related Sources

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Pantheon Books, 1977.

Hille, Koskela. “'Cam Era'—the contemporary urban Panopticon.” Surveillance and Society 2003. 9 Apr 2008 <http://www.surveillance-and-society.org/articles1(3)/camera.pdf>.

Introna, Lucas D., and David Wood. “Picturing Algorithmic Surveillance: The Politics of Facial Recognition Systems.” Surveillance and Society 2004. 9 Apr 2008 <http://www.surveillance-and-society.org/articles2(2)/algorithmic.pdf>.

Koskela, Hille. “‘The gaze without eyes’: video-surveillance and the changing nature of urban space.” Progress in Human Geography 24.2 (2000).

Keuter, Nathan. “The Subjectivity of Eyes in the Sky: Understanding Remote Sensing through the Cuban Missile Crisis and the 2003 Build-Up to War in Iraq.” Seminar Paper. U of Texas at Austin. 2008.

Lee, Jennifer 8. “Caught on Tape, Then Just Caught.” The New York Times 22 May 2005. 9 Apr 2008 <http://www.nytimes.com/>.

Mieszkowski Katharine. “We are all paparazzi now.” www.salon.com 25 Sep 2003. 9 Apr 2008 <http://archive.salon.com/tech/feature/2003/09/25/webcams/index.html>.

Mirzoeff, Nicholas. An Introduction to Visual Culture. London: Routledge, 1999.

Monmonier, Mark S. How to Lie with Maps. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991.

Monmonier, Mark S. Spying with Maps: Surveillance Technologies and the Future of Privacy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002.

Nieto, Marcus, and Kimberly Johnston-Dodds, and Charlene Wear Simmons. “Public and Private Applications of Videa Surveillance and Biometric Technologies.” Mar 2002. 9 Apr 2008 <http://www.library.ca.gov/CRB/02/06/02-006.pdf>.

O'Harrow, Robert. No Place to Hide. New York: Free Press, 2005.

Solove, Daniel J. The Digital Person: Technology and Privacy in the Information Age. New York: New York University Press, 2004.

Sturken, Marita. Practices of Looking: An Introduction to Visual Culture. Oxford: New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Taylor, Nick. “State Surveillance and the Right to Privacy.” Surveillance and Society 2002. 9 Apr 2008 <http://www.surveillance-and-society.org/articles1/statesurv.pdf>.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago