Image Credit: The Harry Ransom Center

Walking through the Harry Ransom Center’s Arnold Newman: Masterclass exhibit with a photographer friend helped me notice more than Newman’s numerous famous subjects. Creating a portrait requires more than just telling someone to smile or to stand in fair light; good photographers must understand how composition affects the final product. Framing matters, whether that’s done by putting wood around a picture or deciding where and how you crop the shot. The exhibit allows visitors to examine Newman’s artistic process, showing the evidence of how he edited his raw photographs into finished portraits. I want to look at in this post both his famous shot of Igor Stravinsky and his created “portrait” of Marilyn Monroe to think more about what we can learn about visual and non-visual editorial practice.

As the exhibit’s catalog states, Newman’s photography was often put into the category of “environmental portraiture.” As William Ewing defines the term, this meant that Newman

would usually situate the person in their library, living room, laboratory, studio or office. But he himself was never comfortable with the term (which is just as well, since today its ecological connotations ring jarringly in our ears). He thought the “environmental” label did not give enough credit to what he termed his “symbolic portraits” [...] Newman also complained that the label was simply too restrictive: “People started calling me the father of the environmental portrait,” he explained, “[but] the moment you put a label on something there is no room to move. And I never thought in such terms, and I refuse to think in terms of labels…” (17)

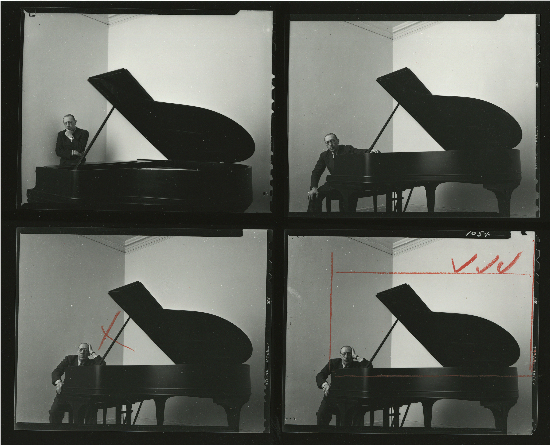

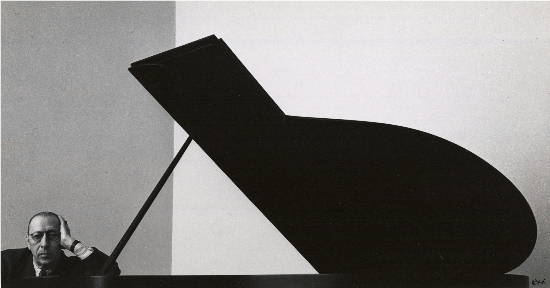

His famous portrait of Igor Stravinsky, which was taken in 1946 when he was commissioned by Harper’s Bazaar’s Alexey Brodovitch to photograph the composer, actually took on a significant afterlife as one of his most famous works, endlessly included in retrospectives of his career. However, it’s worth looking at the negatives to see how this portrait came to be.

Image Credit: The Harry Ransom Center

The contact sheet on display in the exhibit shows four different versions of Stravinsky posed with the grand piano; each contains a different pose, whether it’s him standing with his hand on his chin, or his head tilted back as he sits before the piano. The one Newman marks to use has Stravinsky posing with his left hand against his head and his right hand holding onto the piano, his face posed straight towards the camera. The picture reaches from below the piano to the high ceilings’ crown molding above. Within the photograph’s overall composition, Stravinsky is dwarfed by his surroundings. Yet Newman’s final print makes an even more dramatic cut, choosing to locate Stravinsky in the very far left bottom corner of the picture. The framing here highlights the instrument’s centrality to understanding and representing Stravinsky, as the piano’s highly geometric lid dominates the space, but the picture’s sharp angles draw the eye back to the subject. In other words, by cropping his original picture, Newman creates a more striking portrait, one that lets the viewer feel both Stravinsky’s awe-inspiring musical talent and his gentle humanity.

Image Credit: The Harry Ransom Center

As Jim pointed out in his post, the 1962 Marilyn Monroe series is striking as well, though perhaps more so because Marilyn herself has frequently been the artist’s subject. In his series of photographs with her and Carl Sandberg, viewers can better see how Newman constructs his subject through cropping. William Ewing explains the circumstances surrounding this shoot thus:

The frame itself is one from several rolls of film exposed at a private party ... The actress is shown across the series as relaxed and playful, though a little tired, and the intimate relationship she enjoyed with Sandburg is evident and touching. However, none of this is shown in the selected fragment. One can easily imagine a magnificent Monroe portrait by Newman—one that would have become a famed icon—but the photographer never succeeded in getting the star to pose for him. (101)

The contact sheet for this series shows a variety of Monroe’s playful postures, as well as Newman’s choice of how to crop her for the finished product:

Image Credit: The Harry Ransom Center

Newman’s framing here takes even more dramatic shape than in his Stravinsky portrait, which merely chooses within a composed shot a more striking slice. Here, Newman actually cuts out another person, focusing instead just on Monroe’s face. Ewing’s following commentary on the result is entirely disapproving:

The blow-up was not a portrait in the classic sense. It was not reciprocal; it was not an exchange. Where, in Newman’s approach, the legitimacy of cropping from a 4 × 5 or 8 × 10-inch format was implicit, the same cannot be said of cropping from a casual 35mm negative. The close-up is uncharacteristically grainy and bears no resemblance to the studied compositions of all Newman’s other works. Here, we may have evidence of the corrupting influence of celebrity. Newman could not pin Monroe down, so he took his opportunity to fabricate a “portrait” from the scant materials at hand. (101)

Celebrity may have in fact influenced this creation, if only in how well the portrait’s graininess and Monroe’s pensive expression fit within her larger iconography.

Image Credit: The Harry Ransom Center

Her expression, highlighted by the close crop on her face, invites viewers to see her as isolated, contemplative, or mournful. As created here, the Marilyn we see does not reflect the intimate, relaxed surroundings within the original pictures—recontextualized, it takes on a different, constructed meaning. The insistent "MUST CROP OUT" of the proof sheet emphaiszes that construction as it puts her in a new frame.

Newman’s playful self-portrait of himself posed with the Stravinsky portrait that I opened this post with I think suggests some of what framing does and allows artists, both those who work in visual and written mediums. The contexts and surroundings and cuts you make as author focus the audience’s attention for your own interpretive point—because, if portraits are meant to reveal the subject, what gets revealed is the photographer’s choice, not the subject’s.

The opinions expressed herein are solely those of viz. blog, and are not the product of the Harry Ransom Center.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago