Image Credit: The Harry Ransom Center

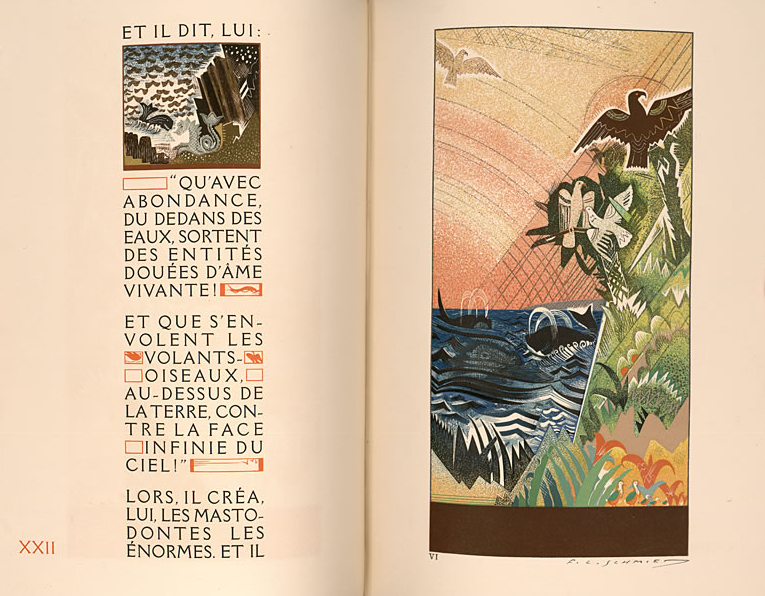

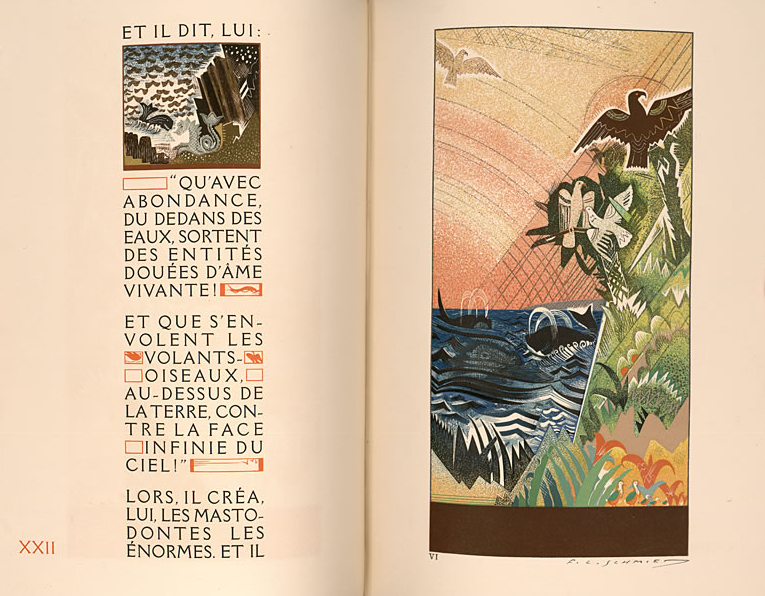

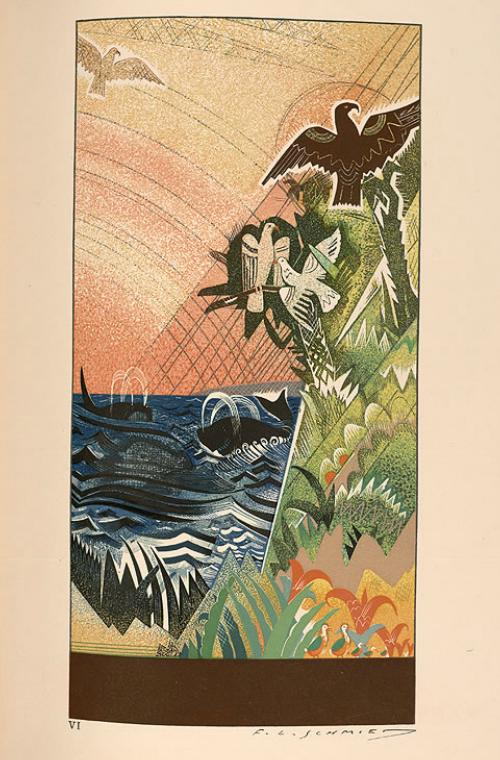

Just before viz. took a break for spring, we visited the Harry Ransom Center’s newest exhibition, The King James Bible: Its History and Influence. Instead of finding only illuminated manuscripts, we were surprised to find contemporary art, literary manuscripts, film posters, and even a sculpture of a golden calf. The exhibition is not just a collection of well-preserved historic Bibles—it’s a unique collection of visual artifacts tangentially related to the King James Bible. As the viz. team walked around the exhibition, one grouping of images caught my eye. Art Deco engraver François-Louis Schmied’s artwork to accompany a French translation of both Genesis and The Book of Ruth from the King James Bible is absolutely stunning. The artwork is most interesting for its fusion of the geometric lines of Art Deco with the Orientalism of its creator and the lyricism of the Biblical stories it illustrates.

Art Deco was a remarkably successful and widespread architectural and artistic movement at the beginning of the twentieth century. The movement was one focused on decoration—the geometric, symmetrical forms of the buildings and drawings of the movement were influenced by ancient Egyptian flourishes. As Edward Said reminds us, since Napoleon’s foray into Egypt in the 18th century, “Egypt was to become a department of French learning.” Along with Napoleon’s soldiers, “chemists, historians, biologists, archaeologists, surgeons, and antiquarians” were tasked with “put[ting] Egypt into modern French.” Started around the heyday of archaeological work in Egypt (King Tut’s tomb was discovered in 1922), Art Deco internalized the general Egyptomania of the times. “Art Deco,” says British historian John M. MacKenzie in his book Orientalism: History, Theory, and the Arts, “though not oriental in any obvious overall way, owed much to oriental influences: the geometrical patterns, often brightly coloured, the strongly projecting corbels, the sunbursts, winged elements, (like clocks rendered as solar discs), and other features.” Most of us are familiar with the architectural epitomes of this style, NYC’s Chrysler Building and Empire State Building. Both of these buildings make use of Egypt-inspired tropes, such as the lotus decorations on the elevators in the lobby of the Chrysler Building.

Image Credit: Archaeology.org

François-Louis Schmied’s artwork to accompany a French translation of the books of Genesis is no different when it comes to using Egypt-inspired visual elements. His depiction of the Creation is composed of brightly colored animals bursting (like sunrays) off the page. The whales spew water in symmetrical arcs, while a tidy group of partridges march along the bottom of the engraving.

Image Credit: The Harry Ransom Center

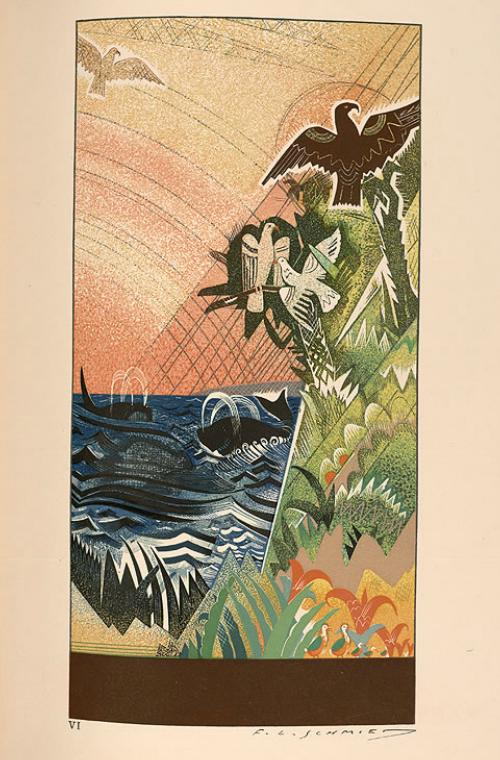

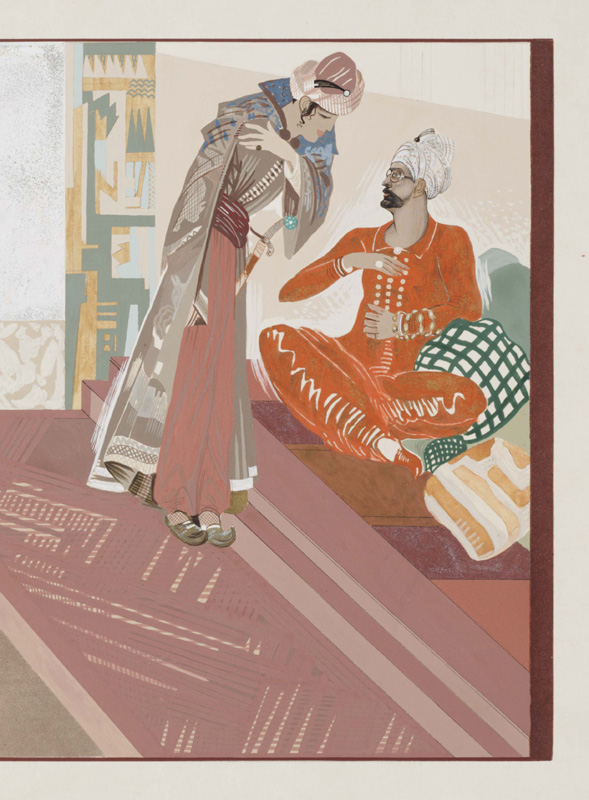

Schmied was an Orientalist in the clearest sense. Working in the 1920s and 1930s, Schmied internalized the Egyptomania of his times. He even painted himself in “Oriental dress” at the beginning of his career in 1927. His willingness to take on the dress of the Other might be a sign of Schmied’s identification with the Orient of the past.

Image Credit: The Bibliographical Society of the University of Virginia

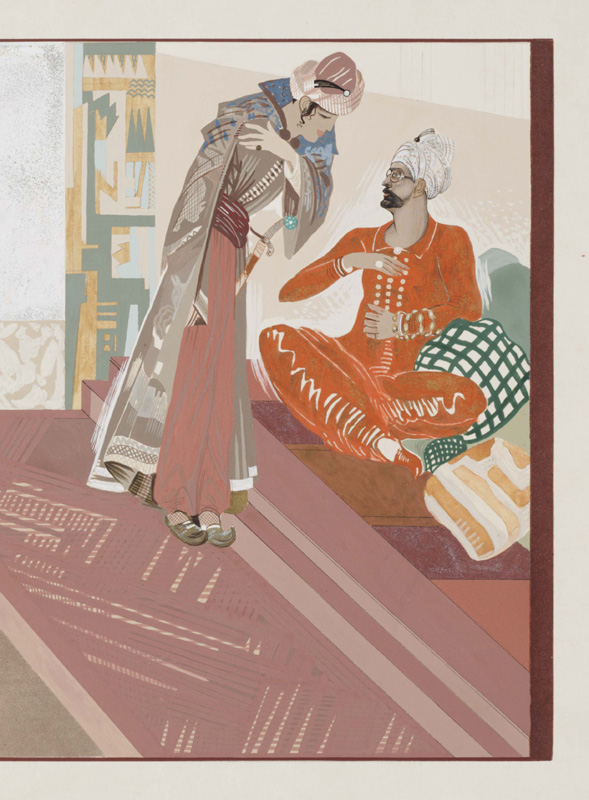

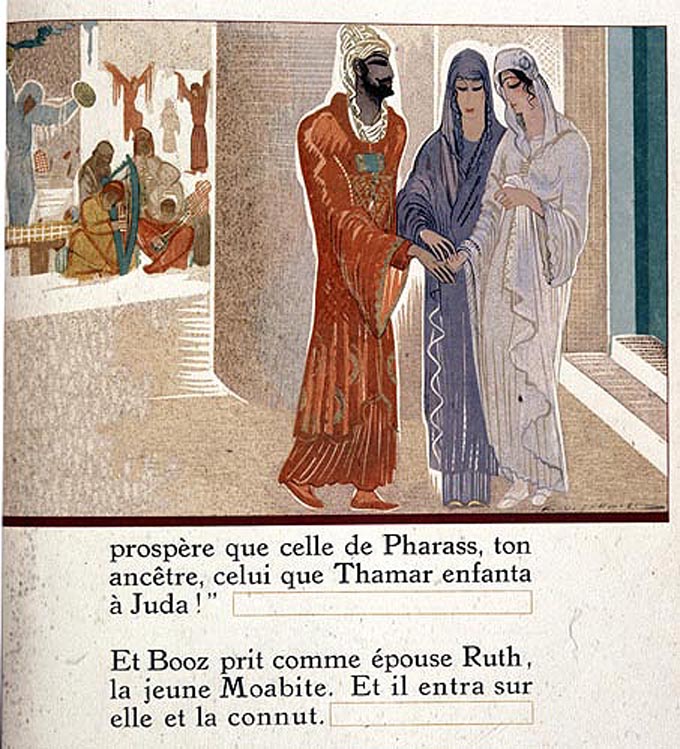

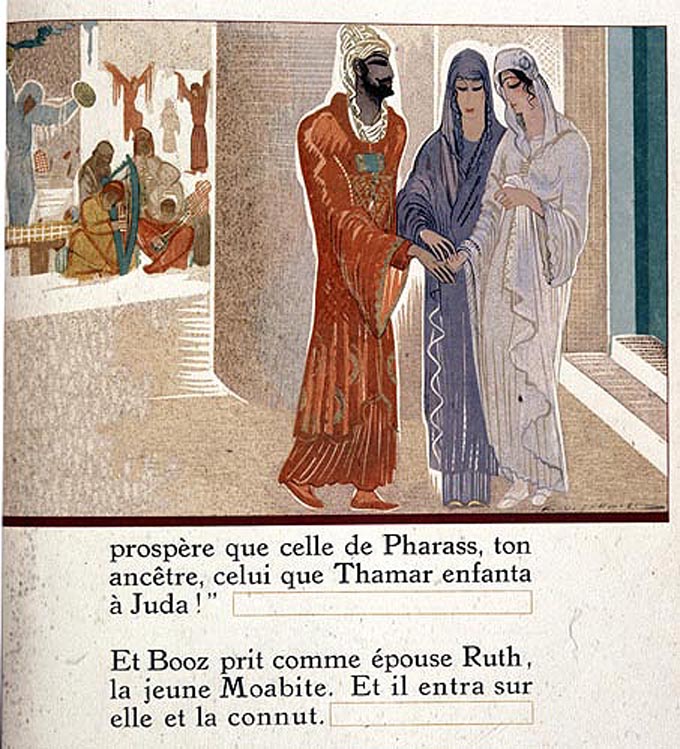

Shmied’s clear investment in the Orientalist project is critical to reading his illustration of the Book of Ruth. In his engraving for the marriage of Ruth and Boaz, Schmied chose to depict Boaz with darker skin than the outsider from Moab, Ruth. Moabites were excluded from the Jewish community as stipulated by God in Deuteronomy 23:3–6.

Image Credit: The Bibliographical Society of the University of Virginia

Ruth, as a Moabite, was allowed to congregate with Israelites because she was a woman (and Moabite women were begrudgingly accepted by Israelites). The story of Ruth and Boaz’s marriage is one of acceptance and compassion—Boaz marries the widowed and impoverished Ruth and fathers a son with her in the direct line of David and Jesus. Their story is not one of passionate love—nowhere does the Bible describe Ruth’s and Boaz’s physical attributes. So, it’s especially interesting that Schmied made Ruth into an olive-skinned beauty and Boaz into a dark-skinned savior. Schmied’s artistic choices might reflect his internalization of another culture, that of “the Orient.” In any case, his engraving is a unique one of an oft-depicted Biblical scene that merits much critical analysis.

See the engravings yourself at the Ransom Center’s exhibition, The King James Bible: Its History and Influence. The exhibition is up until the 29th of July.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago